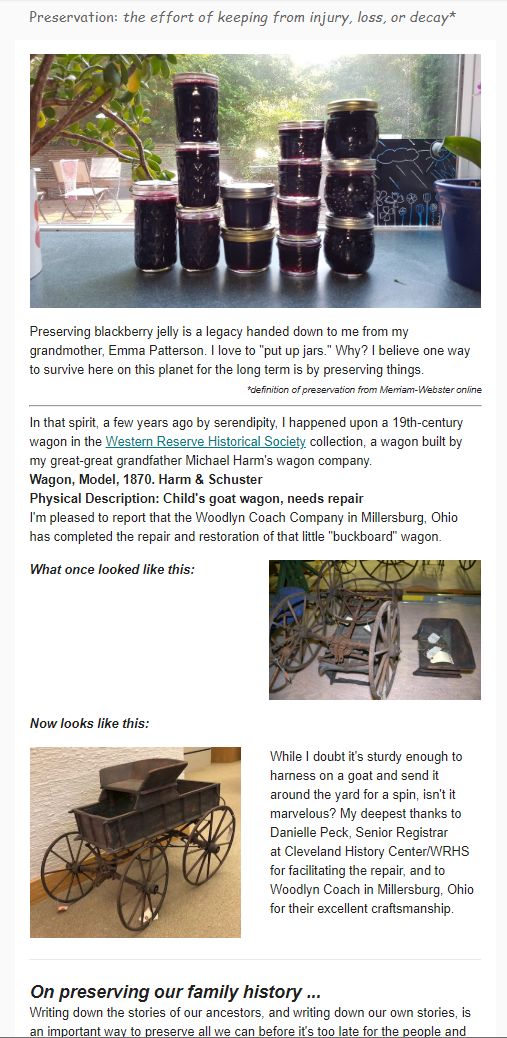

Great news! My memoir How We Survive Here is a Next Generation Indie Book Award Finalist, and a child-sized buckboard wagon made by the Harm & Schuster Company has been completely restored for display at the Western Reserve Historical Society. Also in this May newsletter: 6 tips for forming genealogy writing groups. For the full newsletter, click here:

The Ship of Gold: Fortune’s fool

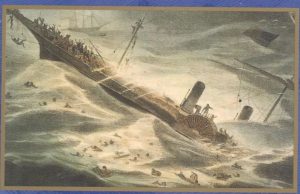

In this morning’s paper, I sat down to an article in the Seattle Times that began “Few have heard of the SS Central America. But it has a place in history because of what happened over three days, beginning on Sept. 9, 1857.”

I’m one of the few. I first heard of the SS Central America, the “Ship of Gold” when researching the life trajectory of my German immigrant ancestor, Michael Harm for my historical novel The Last of the Blacksmiths. Michael Harm arrived in Cleveland, Ohio in July of 1857 to begin a blacksmith apprenticeship with his uncle, and two months later, due to the sinking of the SS Central America, which contained gold intended to back federal paper money, the economy went belly-up. The Panic of 1857 initiated a slump in the U.S. economy that lasted several years.

I’m one of the few. I first heard of the SS Central America, the “Ship of Gold” when researching the life trajectory of my German immigrant ancestor, Michael Harm for my historical novel The Last of the Blacksmiths. Michael Harm arrived in Cleveland, Ohio in July of 1857 to begin a blacksmith apprenticeship with his uncle, and two months later, due to the sinking of the SS Central America, which contained gold intended to back federal paper money, the economy went belly-up. The Panic of 1857 initiated a slump in the U.S. economy that lasted several years.

The sinking of the SS Central America, it turns out, ruined more lives than the 425 people who drowned, the failed businesses, etc. Today’s article is the story of how lives are still being ruined, even in 2019. The book Ship of Gold In the Deep Blue Sea (1998), by Gary Kinder, recounts the original sinking of the SS Central America in 1857 and its consequences, and also treasure-hunting efforts in the Atlantic that occurred from 1986-1988. But it’s not until this year, 2019, that those 13 treasure hunters, “most from the Seattle area,” have finally concluded lengthy court battles and earned a fraction of their find.

They were the engineers, technicians and owners of high-end sonar equipment who were promised a small share of the wreck’s bounty in return for their work, which found the Central America in 1988, some 160 miles off the South Carolina coast, 7,200 feet down on the ocean floor.

It took nearly 30 years of litigation and reams of legal documents before a court settlement got them at least a portion of what they were owed. The last of two payments arrived in February.

Full article in The Seattle Times.

The leader of the expedition apparently absconded with $50 million, suffered a failed marriage, and is now in federal prison.

Trouble in this tale includes the main visionary in the treasure hunt – a man named Tommy Thompson, now 66. He sits in an Ohio federal minimum security prison because he won’t divulge where 500 new gold coins struck from the Central America’s bounty have been hidden.

There’s a life lesson here. We seem bound to allow material things to wreck us. Even Ship of Gold author Gary Kinder, who took ten years to write his book, lost his father and his brother to death during those years, and his mother suffered a series of strokes and had to enter a nursing home. Kinder also mentions in his Acknowledgements that his “daughters have hardly known [him] when he was not working on ‘the book’.” Kinder sums up that these things were “all teachings of the bitter lesson that while we are tending relentlessly to one part of our lives, the other parts do not stand still.”

It strikes me as a reflection of how we survive here, a reminder to appreciate what we have, and just maybe, to focus less on material gain and more on quality time with loved ones.

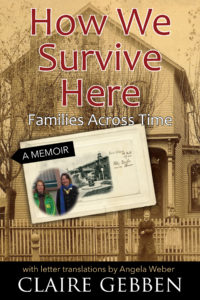

It’s really happening! Another book!!

It’s happening! My book How We Survive Here: Families Across Time is being released this November. It’s already up and available for pre-order on Amazon.*

It’s happening! My book How We Survive Here: Families Across Time is being released this November. It’s already up and available for pre-order on Amazon.*

What a journey. Back in 2008, my German cousin Angela Weber visited me, bringing along 19th-century letters written in Old German Script by my German immigrant ancestors. Angela knew how to translate the letters, a true blessing. Otherwise their contents would still be a mystery.

I wrote my historical novel The Last of the Blacksmiths (2014) based on the people of those letters, blacksmiths and wagon-makers to Cleveland, Ohio in the mid-1800s. I fictionalized the story to universalize it, but Angela pressed for something more — the actual publication of the letters to make them available to all. She was right, of course. In addition to their value for historians, the letters also contain many surnames of other German immigrants, something of value to genealogists.

As we got going on the project (the letter translations in the book are by Angela), How We Survive Here became so much more than letters, eventually transforming into a full-fledged memoir. It’s the story of:

As we got going on the project (the letter translations in the book are by Angela), How We Survive Here became so much more than letters, eventually transforming into a full-fledged memoir. It’s the story of:

Last but not least, How We Survive Here was written in the hope it will inspire and help many others as they explore and write up their family histories.

The release date (November 10, 2018) is one month and counting, so here we go. Thanks to all of you for coming along on the journey.

*Though it’s convenient to shop on Amazon, I believe it’s also important to support your local bookstore, another place you can order a copy. Or, request that your local library add it to their collection.

Posted in Uncategorized

Americana and other delights

The bike trip is over now, but fond memories linger. Along the C&O and GAP bike trails, several diners displayed entertaining signage. A few of my favorites:

In Cumberland, Maryland, I passed by and peeked into the window of Ned’s Barber Shop (closed until further notice) and was wowed by the decor:

Lastly, in this little book on the coffee table at the Allegheny Trail House B&B, the collection of thoughts on bicycling were delightful, just a couple of which I offer here.

Lastly, in this little book on the coffee table at the Allegheny Trail House B&B, the collection of thoughts on bicycling were delightful, just a couple of which I offer here.

Progress should have stopped when man invented the bicycle. — Elizabeth Howard West

The Bicycle is a curious vehicle. Its passenger is its engine. — John Howard

It is by riding a bicycle that you learn the contours of a country best, since you have to sweat up the hills and can coast down them. — Ernest Hemingway

How does it end?

It ends, Angela and my two-week long, 300+ mile bike tour of the C&O and GAP Trails, with an extremely long ride out of Ohiopyle.

It ends, Angela and my two-week long, 300+ mile bike tour of the C&O and GAP Trails, with an extremely long ride out of Ohiopyle.

“People make it to Pittsburgh in one day,” one resident of Ohiopyle told us.

Apparently, we are not those people. Then again, Angela and I didn’t set off on Friday until mid-afternoon, reason being we couldn’t resist taking a tour of Fallingwater, the famous Frank Lloyd Wright-designed house that sits on top of a waterfall. Amazing.

Apparently, we are not those people. Then again, Angela and I didn’t set off on Friday until mid-afternoon, reason being we couldn’t resist taking a tour of Fallingwater, the famous Frank Lloyd Wright-designed house that sits on top of a waterfall. Amazing.

Since the trail by now is leaving the Allegheny mountains, one might assume there are more places to stay en route to Pittsburgh. There are not. As the sun sets, Angela and I are working all the angles (do you think that guy with the pick-up would give us a lift?), but come up with zip. Then, at our darkest and weariest hour (about 7:30 p.m.), we happen upon “trail angels” who set us up in a cozy cottage for the night and feed us farm-fresh eggs in the morning. Kindness abounds.

You know you’ve reached Pittsburgh when the trail turns from dirt to pavement. It being a Saturday, we encounter traffic–not only cars, but bicyclists. During the final few miles Angela and I are swarmed by “beer riders” pedaling back from a beer festival. They slow their pace to match ours and ask us where we’re from. Word passes up and down the line: “Seattle” “Germany” “They made it all the way from DC.” which puffs us up with pride and keeps our tired legs pumping along. Ten or twelve of us barrel along for a good stretch, until we reach a major intersection.

You know you’ve reached Pittsburgh when the trail turns from dirt to pavement. It being a Saturday, we encounter traffic–not only cars, but bicyclists. During the final few miles Angela and I are swarmed by “beer riders” pedaling back from a beer festival. They slow their pace to match ours and ask us where we’re from. Word passes up and down the line: “Seattle” “Germany” “They made it all the way from DC.” which puffs us up with pride and keeps our tired legs pumping along. Ten or twelve of us barrel along for a good stretch, until we reach a major intersection.

The woman next to me shouts: “Are we veering?”

“We’re veering!” Someone else yells.

The group splits, riders heading off in several directions. Back together again, Angela and I head up over our last bridge of the trip, which siphons us between two highways toward the official end of the trail at Point State Park. The Park sits at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers, which join together here to become the mighty Ohio. We stare out over the water for a while, then turn to look behind us and capture this iconic view of Pittsburgh.

Odds and ends

When Angela and I stopped at a vista in Confluence, PA, we learned George Washington had camped here in May of 1754. In Washington’s diary, he wrote: “We gained Turkey-foot, by the Beginning of the Night.” The area was then called Turkey-foot because it’s where three rivers meet: Casselman River, Laurel Hill Creek, and the Youghiogheny (pronounced yock-a-ganey). All joining together into one, like the turkey foot above.

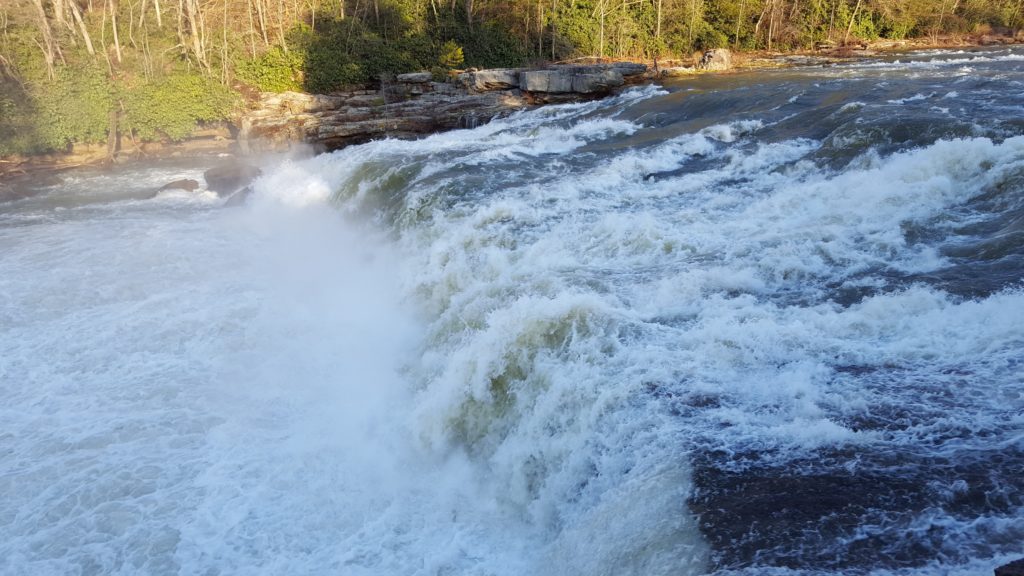

Water sports are big here. River rafting, kayaking. But they’re not happening now. April is pre-season, when those businesses are all shuttered. And for good reason. The roar of the snowmelt river is mighty indeed.

Black walnuts

The black walnut trees we’ve seen have been sturdy and prolific. European walnut trees did not thrive here, but the endemic Black Walnut does fine. Native Americans harvested black walnuts, and also used the trees’ sap in their cooking. A comprehensive history of the walnut tree is found here.

The black walnut trees we’ve seen have been sturdy and prolific. European walnut trees did not thrive here, but the endemic Black Walnut does fine. Native Americans harvested black walnuts, and also used the trees’ sap in their cooking. A comprehensive history of the walnut tree is found here.

It is said early German immigrant settlers looked for land with stands of black walnut trees, since their presence indicated good soil with plenty of lime.

You might enjoy reading about black walnut tree lore handed down by the Goschenschoppen Pennsylvania community here, from which I lifted the following excerpt:

An old almanac in the Goschenhoppen Folklife Library contains a woodcut showing a farm boy with a baseball-bat size club whacking away at a walnut tree. The late Thomas R. Brendle records the practice of waking-up young fruit and nut trees that are reluctant to start bearing by beating them with a club. The folk practice dictates that the trees were to be beaten on New Year’s Day in the morning without speaking. A current arborist writes that this is not complete nonsense. Apparently if a young apple tree, for example, has reached the age when it should start to bear and it just doesn’t flower, during the winter when it is dormant a beating with a padded club and a vigorous twisting of the limbs traumatizes and shocks the tree into its normal cycle.

Posted in 18th century history, Travels

Tagged Confluence PA, North American black walnut trees, Turkey Foot

Over the hump

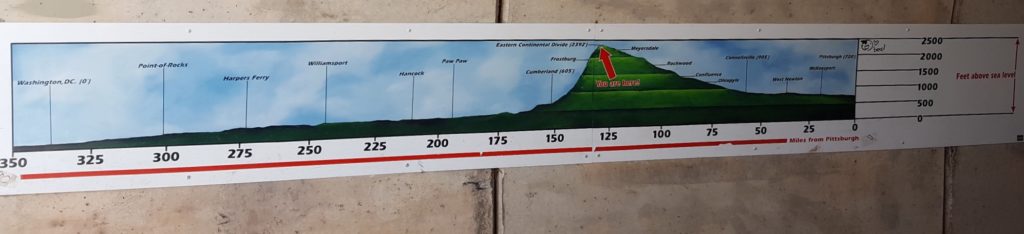

It was snowing in Frostburg (yes, really), so Angela and I postponed for one day our departure from Maryland into Pennsylvania. The map here indicates elevation gain to the Eastern Continental Divide, so you get the idea.

Before you get too excited, let me just say our climb to this point from Washington, DC rarely amounted to more than a 1.5 percent grade. That’s why it took us eight days to get to Frostburg. Which is a lot, since, when we looked at driving the same distance by car, Google maps informed us the trip would take 2 hours and 17 minutes.

“Just don’t think about it,” Angela said.

After snow flurries and bitter wind all day Tuesday (while we languished in the Allegheny Trail House B&B), Wednesday dawned sunny and bright.

At a viewpoint on the Maryland side, we found someone to take our picture.

At a viewpoint on the Maryland side, we found someone to take our picture.

“You’ll love the tunnel,” the man said as we parted ways.

Tunnel? Sure enough, just around the bend we encountered the Big Savage Tunnel, 3,295-feet long, which earns this write-up on the National Park Service website.

Big Savage Tunnel [is] named for surveyor Thomas Savage who, along with the rest of his party, was stranded here in the winter of 1736. According to the legend, he offered himself up as food to save the rest of the party from starving. A rescue team showed up, saving Savage’s life. His companions were so grateful that they named the Savage River for him.

We had a headlamp all set to go, but the tunnel was well-lit by ceiling lights. Cold, though. Icicles dripping throughout.

We had a headlamp all set to go, but the tunnel was well-lit by ceiling lights. Cold, though. Icicles dripping throughout.

We knew we’d reached the border with Pennsylvania when we crossed the Mason-Dixon Line. The monument made me strangely sad on such a beautiful day, as I thought of family feuds (the original reason for the Mason-Dixon had to do with a 1760s feud between the Penn and Calvert families) and the terrible bloodshed of the Civil War.

We knew we’d reached the border with Pennsylvania when we crossed the Mason-Dixon Line. The monument made me strangely sad on such a beautiful day, as I thought of family feuds (the original reason for the Mason-Dixon had to do with a 1760s feud between the Penn and Calvert families) and the terrible bloodshed of the Civil War.

We didn’t linger long. In twenty more miles (downhill at last), we reached Rockwood and the Mill Shoppe, Americana at it’s finest.

Posted in 18th century history, Travels

The legend of Cash Valley

I have no doubt the homeowners along Cash Valley Road are mighty sick of people asking them how their road got its name. This sign stood right at the GAP Trail intersection, so of course Angela and I stopped to snap a few photos.

I have no doubt the homeowners along Cash Valley Road are mighty sick of people asking them how their road got its name. This sign stood right at the GAP Trail intersection, so of course Angela and I stopped to snap a few photos.

It appeared to be a fertile valley, so perhaps, I speculated, the people here had done very well with farming?

A little farther up the mountain, we happened upon a victim to ask, an elderly man out walking the trail. He paused and leaned against a fence, hands in his pockets like he had all day, presumably to let us pass.

Only we didn’t. We stepped down off our bikes, greeted him and exchanged pleasantries. When I said I was from Seattle, he said he’d been there a couple of times, the first time during the war when he’d shipped out of Bremerton. Quite a few people I’ve met know the Northwest via military service, via McChord Air Force Base in Tacoma, say, or the Naval Station at Bremerton.

“So, what’s the story behind Cash Valley?” I couldn’t resist asking.

“Oh, it’s a long one,” he said. “I can’t remember the specifics. There was a rumor someone buried cash here, and people kept returning to dig for it. I don’t know if they ever found it or not.”

Ah. This must have been a common story along the wilderness road. In the book The Old Pike: A History of The National Road with Incidents, Accidents, and Andecdotes Thereon (1894) by Thomas A. Searight, I came across the following:

It was reported in Ohio that there was a box of money hid on the old Gaddis farm, near the old pike, about two miles west of Uniontown, [PA] supposed to have been hid there by Gen. Braddock. It was sought for but never found.

General Braddock would have been in Uniontown circa 1755, so that money’s been hidden away for centuries. Angela and I expect to pass Uniontown in the next couple of days. Perhaps we should stop and buy a shovel?

Posted in 18th century history, 19th century history, Travels

Tagged Cash Valley MD, GAP Trail, National Road lore

Saying farewell to the C&O

In Cumberland, MD, Angela and I said farewell to the C&O Canal Trail. So are we done with our journey? Oh, my no. We’re over a week in, and we’ve only reached the halfway point.

In Cumberland, MD, Angela and I said farewell to the C&O Canal Trail. So are we done with our journey? Oh, my no. We’re over a week in, and we’ve only reached the halfway point.

Next up, the Great Allegheny Passage (GAP) Trail out of downtown Cumberland, pedaling northwest to Frostburg. Eight miles by car, a steady sixteen miles uphill by bicycle.

Next up, the Great Allegheny Passage (GAP) Trail out of downtown Cumberland, pedaling northwest to Frostburg. Eight miles by car, a steady sixteen miles uphill by bicycle.

Oh, you’re thinking, that’s bad.

No, that’s good. The journey is twice as long to keep the grade of incline at one percent. A slog, but doable. Feel the burn.

No, that’s good. The journey is twice as long to keep the grade of incline at one percent. A slog, but doable. Feel the burn.

And soak up the scenery. Along the way we passed by the Cumberland Bone Cave where skeletal remains were found dating back 200,000 years, to the Pleistocene Era.

And soak up the scenery. Along the way we passed by the Cumberland Bone Cave where skeletal remains were found dating back 200,000 years, to the Pleistocene Era.

On one stretch we spotted four or five quite enormous wild turkeys (they’re fast, so they got away before we could take photos) who left large three-toed tracks in the cinders reminiscent of dinosaur footprints (or maybe the bone cave had captured our imaginations?)

On one stretch we spotted four or five quite enormous wild turkeys (they’re fast, so they got away before we could take photos) who left large three-toed tracks in the cinders reminiscent of dinosaur footprints (or maybe the bone cave had captured our imaginations?)

Every so often along the way, we happen upon an interpretive sign that peels back a layer of history. A sign positioned before the valley view of Mt. Savage informed us:

The Community of Mt. Savage … was originally referred to as “Arnold’s Settlement” in about 1780. The Arnold family had established themselves here … along an old American Indian trail west. … The settlement served as an overnight stop for travelers moving westward to the Ohio River.

Posted in 18th century history, General, Travels

Tagged C&O Canal trail, Cumberland Bone Cave, GAP Trail

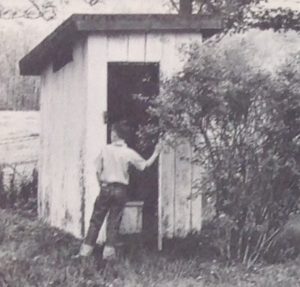

A word about privies

Privies, also called outhouses, can also be a worthy subject of history, can’t they? A part of everyday life. Privies used to be a common sight on every farm. They were located near, but not too near, the main building, and came in varying sizes — one-holers, two-holers, etc. Sometimes, there were two privies, one for men, one for women. Signs would be posted on the doors saying which was which, or the genders could also be distinguished by a crescent moon for women and a star for men.

Privies, also called outhouses, can also be a worthy subject of history, can’t they? A part of everyday life. Privies used to be a common sight on every farm. They were located near, but not too near, the main building, and came in varying sizes — one-holers, two-holers, etc. Sometimes, there were two privies, one for men, one for women. Signs would be posted on the doors saying which was which, or the genders could also be distinguished by a crescent moon for women and a star for men.

Speaking of which, on the C&O Canal Trail, the National Park Service supplies a privy, aka a port-a-potty, every five miles or so. For the most part, they’ve been well-maintained and even have toilet paper.

Speaking of which, on the C&O Canal Trail, the National Park Service supplies a privy, aka a port-a-potty, every five miles or so. For the most part, they’ve been well-maintained and even have toilet paper.

In the comfort of today’s “privies,” owners sometimes feel inspired to elevate the mood of the visitor. In Hancock, we stopped for dinner at Buddy Lou’s along the Canal. In the restroom, I happened upon a framed three-stanza poem, a vase of flowers beside it, the first stanza of which follows.

The Trail to Hancock

I took the trail to Hancock all

in the sweet May weather,

Through Frederick and

through Hagerstown, with

heart as light as a feather,

The trail that climbs the

mountains so, goes

over peak by peak,

And the dogwood and the judas

trees made every moment speak.

B.B.

Posted in Uncategorized