Do you know about the Google Alerts feature in your Google account? I first learned about it when blogging for genealogy research. I mentioned Johann Rapparlie in a post, and someone researching the Rapparlie surname contacted me. She and I had a beneficial exchange. I shared Rapparlie’s letter translations with her, and she shared a ton of Rapparlie surname research with me.

Do you know about the Google Alerts feature in your Google account? I first learned about it when blogging for genealogy research. I mentioned Johann Rapparlie in a post, and someone researching the Rapparlie surname contacted me. She and I had a beneficial exchange. I shared Rapparlie’s letter translations with her, and she shared a ton of Rapparlie surname research with me.

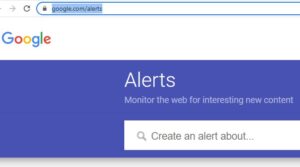

What exactly is Google Alerts? Follow these instructions on this Family Search blog to get started. Once you enter your keyword(s), Google will alert you via email when new content on that keyword appears.

One of my Google Alerts is the title of my historical novel, The Last of the Blacksmiths. (My publisher recommended I do this.) A couple of times a month, I receive an email about websites where those key words are found. In this way, “last blacksmiths” scroll through my inbox queue regularly. A few recent examples:

November 29, 2022: Robert Kelly Remembers His Grandfather Dick Bulmer, the last traditional blacksmith in Victoria County.

November 10, 2022: Meet One of the Last Blacksmiths in Israel. Walied Khoury is one of only eight traditional blacksmiths in all of Israel.

August 28, 2022: Blacksmiths Pinning Hopes on Eid-ul-Azha Sales. Afghanistan blacksmiths see in increase in sales of butchery knives at the time of Eid-ul-Azha, a Muslim Holy Festival.

August 2, 2022: The Last Titans: Kashmir’s Once Famous Master Blacksmiths Are On Their Way Out.

Of course, other “last blacksmith”-related emails arrive too: blacksmith characters that appear in Evil Dead and other multiplayer games, Blacksmiths Lacrosse, a team out of Luxembourg, Lego blacksmith village sets on sale for Black Friday, etc. Those are equally of interest. They cause me to reflect on blacksmith mythology, how the grit and sweat of the ancient craft is gradually being subsumed.

As a book title, The Last of the Blacksmiths receives pushback from blacksmiths still engaged in the craft today. My intent is not to dismiss their impressive work. In fact, around the world there is increased interest in blacksmithing. That said, traditional blacksmithing has almost completely died out.

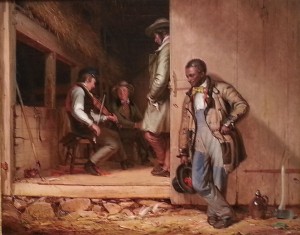

Once upon a time, blacksmiths were the underpinnings of society for just about everything, from farm tools to wagons to knives to nails. They were society’s troubleshooters before the age of machines and technology set in. When remembering his grandfather Dick Bulmer, Robert Kelly explains:

[Grandfather] made his living fabricating whatever people needed. Many of his older customers wanted parts for old farm equipment—threshing machines, combines, hay rakes, and so on. They would come in and bring or describe what they needed, and Dick would sketch a picture on the back of an old envelope. Once they figured it out together, he would get to work at the forge.

I recommend a look at the entire article about Dick Bulmer. It gives a flavor of traditional blacksmithing and the vital role blacksmiths played in communities of old.