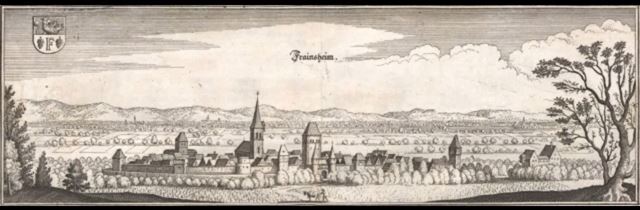

My cousin in Germany found land records for my ancestors (in the Landesarchiv in Speyer) and her English skills are impressive, so she did me the favor of translating and explaining the documents.

“The sizes of the land pieces are measured in an old Bavarian unit. Tagewerk, which means ‘a day’s work’ and Dezimalen, which is the 100th part of one Tagewerk. One Dezimal is 34.07 square meters, and one Tagewerk is 100 Dezimale, or 3,407 square meters.” [I found substantiation of this measurement, and others, in a google books document: The Science of Measurement: A Historical Survey by H. Arthur Klein. 3,407 square meters equals .84 of an acre.]

My cousin also noted the four fields in four separate locations were described as being hinter der Burg (behind the castle), in der Thalweide (in the valley pasture) and so on. “The first piece is a vineyard (Wingert) of 32 Dezimale. The second piece is a field (Acker) of 34 Dezimale.” An interesting side note is that the fields were not located all in one place. My cousin tells me this was a kind of insurance, to protect against total crop loss if, for example, one field was hit by hail, or another by frost, etc.

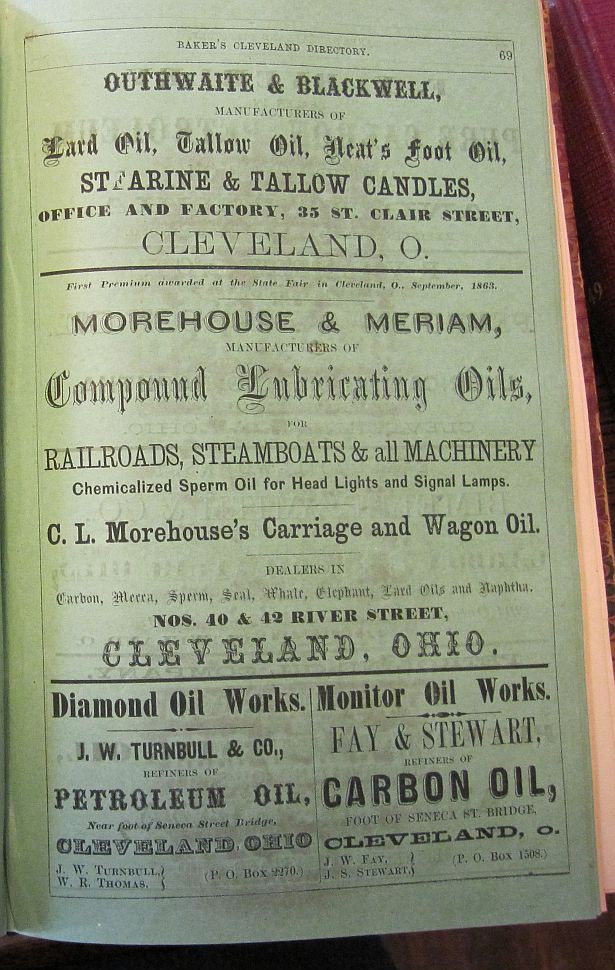

The land records were in the “Kataster-Buch,” which was started by the Bavarian state (rulers of the Palatinate in that time period) in 1840 noting each landowner of the community and his property for tax reasons.

Persons who know German will have paused above at “vineyard (Wingert)” because the German word for vineyard is “Weinberg.” Isn’t it?

Now we’re talking dialects. When I briefly studied German in college, I learned there were two varieties, High German and Low German. I had no idea that each of those were also splintered into many different dialects.

Today, the German word most commonly used for farmer is Bauer, but in my ancestor’s day, the farmer (as opposed to the wine grower–Wingertsmann) was known as an Ackermann. Wait, Ackermann, as in “acre man?” Sorry, while my brain makes that association, the direct translation is husbandman, an archaic word by English standards, too. According to Merriam-Webster, a husbandman is one who plows and cultivates fields.

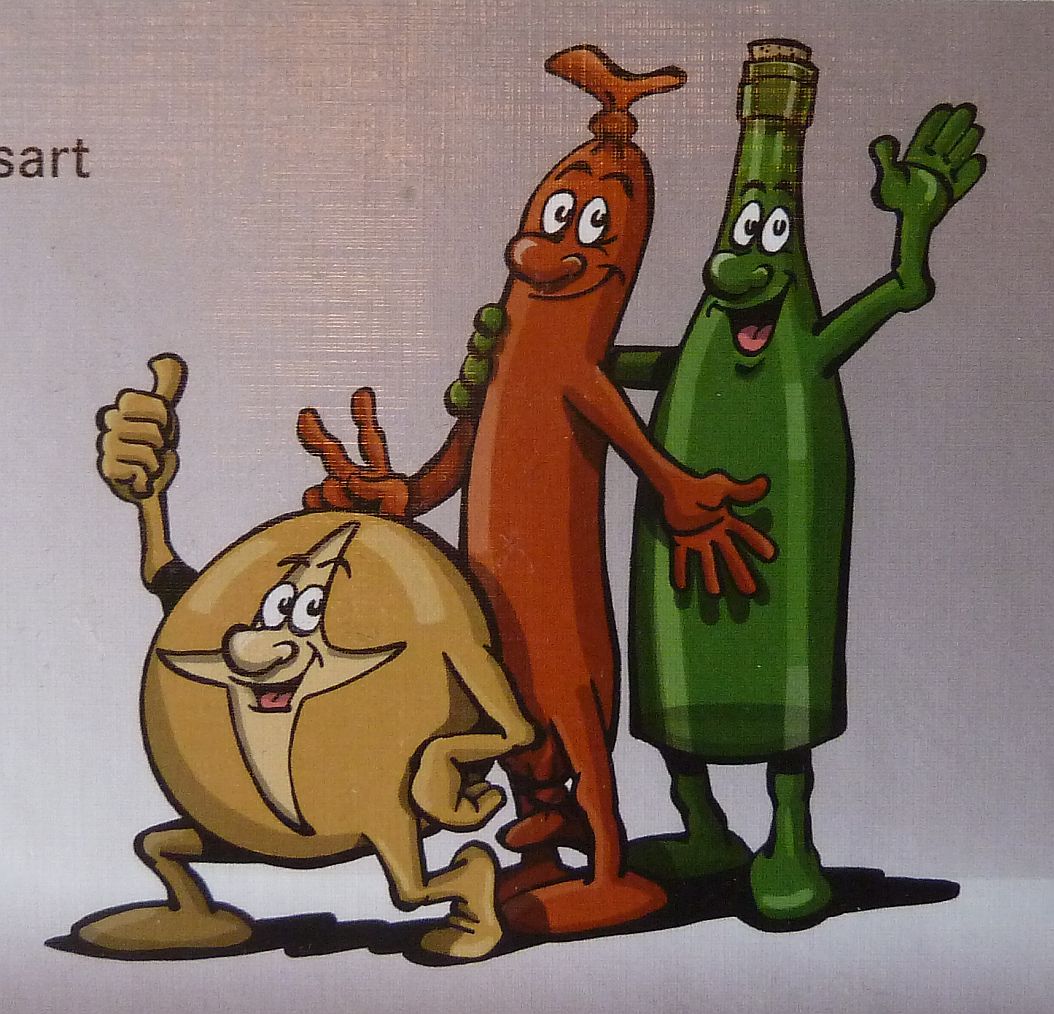

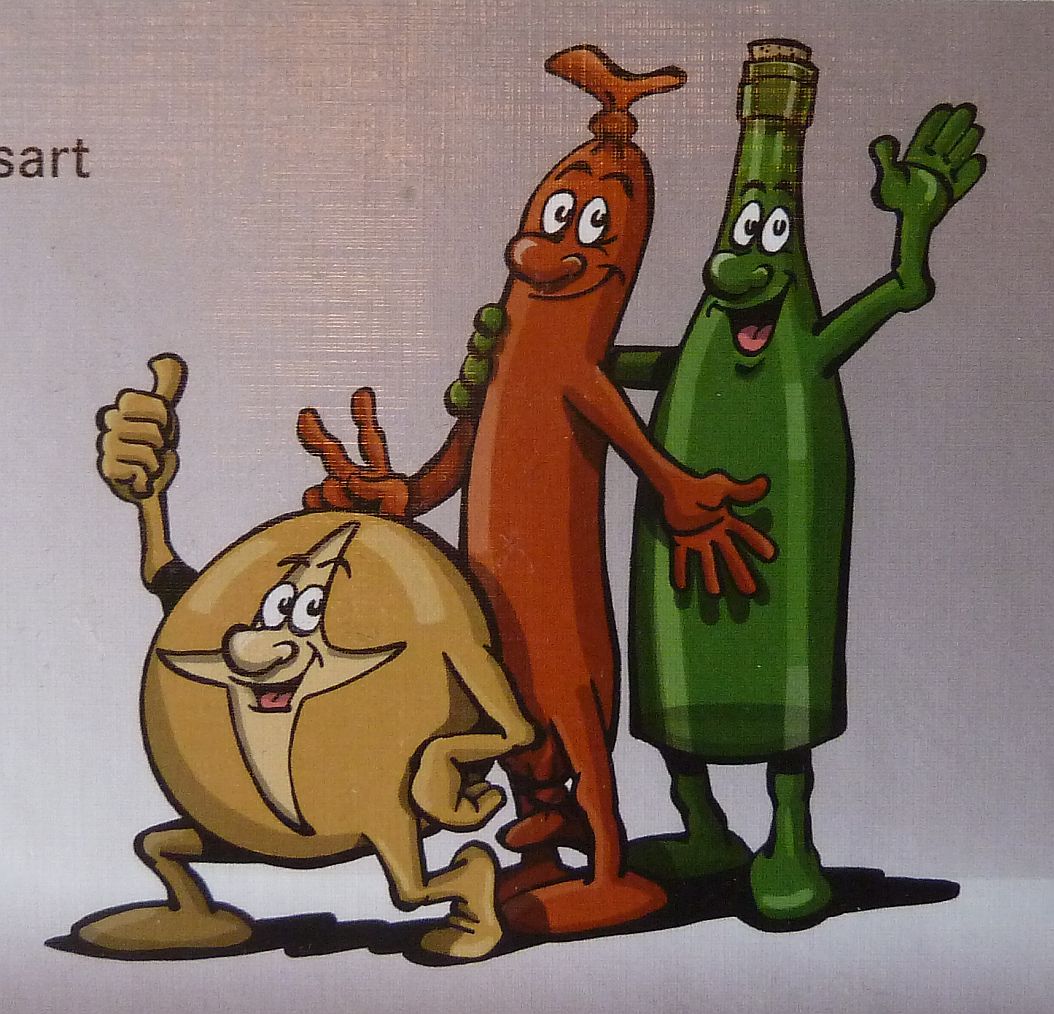

Regional dialect in the Palatinate is not as common as it once was, but it is still in use. This humorous book by Uwe Hermann, Die Abenteuer von Weck, Worscht & Woi: Der Wegweiser zur Pfälzer Lebensart (Weck meaning bread in Palatine dialect, Worscht meaning wurst or sausage, and Woi meaning wine) gives a glimpse into the dialect and culture. My relative Matthias sent it to me when I kept nagging him about Palatinate words. A translated title of the book would be: The Adventures of Bread, Wurst, and Wine: The Guide to Palatine Living. In the book, a cartoon bread, sausage, and bottle of

wine explore the humor, confusion and frustration sometimes created by the Palatine dialect, and also the fun-loving spirit of the people. A helpful glossary is provided beside each cartoon. Even some French words have seeped into the dialect (for instance, bottle is “Buddel (bouteille)” instead of “Flasche”). In part, this French influence came about because France ruled the Palatinate from 1794-1815, first by the French revolutionary armies, later by Napoleon.

wine explore the humor, confusion and frustration sometimes created by the Palatine dialect, and also the fun-loving spirit of the people. A helpful glossary is provided beside each cartoon. Even some French words have seeped into the dialect (for instance, bottle is “Buddel (bouteille)” instead of “Flasche”). In part, this French influence came about because France ruled the Palatinate from 1794-1815, first by the French revolutionary armies, later by Napoleon.

At a recent visit to the Western Reserve Historical Society’s Crawford Auto Aviation Collection, I was delighted to find this example, circa 1916, of a Rauch & Lang electric car.

At a recent visit to the Western Reserve Historical Society’s Crawford Auto Aviation Collection, I was delighted to find this example, circa 1916, of a Rauch & Lang electric car.