I’m currently studying Highland Gaels due to a branch of my family ancestry, and also as the subject of my next historical novel. In the process, I’ve happened upon the Hidden Glen Folk School, established by Dr. Michael Newton, Ph.D. to recover the best of Highland Gaelic tradition through Gaelic histories, songs, stories, poems, language, and practices. The school has been a breakthrough for me as I endeavor to sort through distinctions between Highland Scots, Lowland Scots, and the Scots-Irish.

Through a Hidden Glen classmate, I’ve learned something not on my radar — the “Irish Palatines.” Seriously? Irish Germans? Is that really a thing? Yes, it is.

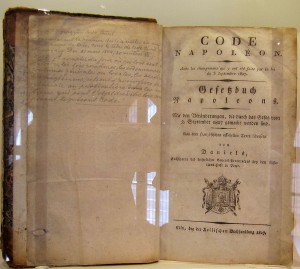

The term Palatines, or people of the Palatinate (German Pfalz), refers to people living in a region of southwest Germany. According to Britannica,

The Rhenish Palatinate included lands on both sides of the middle Rhine River between its Main and Neckar tributaries. Its capital until the 18th century was Heidelberg. … The boundaries of the Palatinate varied with the political and dynastic fortunes of the counts palatine.

Did they ever. This Sunday, April 3, I’ll be presenting a webinar on the topic Explore the Rhineland-Palatinate for the Irish Palatine Special Interest group of the Ontario Genealogical Society and will give an overview of those “political and dynastic fortunes,” wars, religious persecutions, and more. (Click here for more info and to register.)

Now for the Irish part. In the early 1700s in the Palatinate, after devastating scorched-earth wars, famine, and religious persecution, many Palatines had grown desperate. Enter Protestant Queen Anne of England (1702-1714) who viewed the Protestant Palatines as victims of religious persecution, and also sought to increase the number of Protestant subjects then in Ireland. Meanwhile, due to reports that a better life awaited in North America, the thoughts of the Palatine peasants “were turned toward America [in part] through what seemed like an invitation from Queen Anne of England to settle in her transatlantic colonies.” [from Don Heinrich Tolzmann’s book, The German American Experience, p. 57] By October of 1709 about 15,000 Palatines had voyaged to London with hopes of settling in British America. They became known by the English as the “poor Palatines.” Never mind that fewer than half were Palatines.

Now for the Irish part. In the early 1700s in the Palatinate, after devastating scorched-earth wars, famine, and religious persecution, many Palatines had grown desperate. Enter Protestant Queen Anne of England (1702-1714) who viewed the Protestant Palatines as victims of religious persecution, and also sought to increase the number of Protestant subjects then in Ireland. Meanwhile, due to reports that a better life awaited in North America, the thoughts of the Palatine peasants “were turned toward America [in part] through what seemed like an invitation from Queen Anne of England to settle in her transatlantic colonies.” [from Don Heinrich Tolzmann’s book, The German American Experience, p. 57] By October of 1709 about 15,000 Palatines had voyaged to London with hopes of settling in British America. They became known by the English as the “poor Palatines.” Never mind that fewer than half were Palatines.

No more than half of the so-called German Palatines originated in the namesake Electoral Palatinate, with others coming from the surrounding imperial states of Palatinate-Zweibrücken and Nassau-Saarbrücken, the Margraviate of Baden, the Hessian Landgraviates of Hesse-Darmstadt, Hesse-Homburg, Hesse-Kassel, the Archbishoprics of Trier and Mainz, and various minor counties of Nassau, Sayn, Solms, Wied, and Isenburg. [From German Palatines, on Wikipedia]

Also never mind that they weren’t all Protestants. Apparently some 2,000 were Catholics (from Wikipedia “German Palatines,” see link above). In any event,

Over 800 families, comprising more than 3000 people, were sent on to Ireland between September 1709 and January 1710. Most left again within a few years, for England or America, but 150 families settled in Rathkeale, County Limerick and thrived in the production of hemp, flax and cattle. A second successful settlement of Palatine families took hold near Gorey in Co. Wexford around the same period. [from Goethe Institute’s “Irish Palatines”]

These persons were among the first wave of Palatine emigrants. Surnames of the persons sent to Ireland in this era can be found at the Library Ireland website.