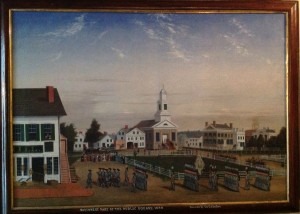

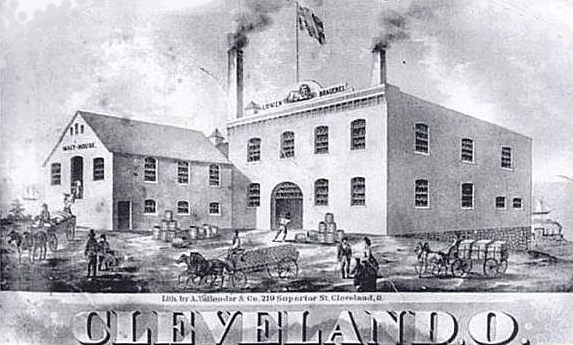

We can stare at old photos, such as this picture of my great-great grandfather’s Cleveland carriage works, for a long time without grasping the signficance of what we see.

We can stare at old photos, such as this picture of my great-great grandfather’s Cleveland carriage works, for a long time without grasping the signficance of what we see.

The horseshoe above the door here is a bit blurry, but I assume the immediate significance of such a symbol meant it was the entrance to the smithy (since blacksmiths were sometimes also farriers who shoed horses). At “Horse Quotations and What They Mean” I found the following in item #2: “Hang a horseshoe over the door for good luck.”

There is … a legend from the middle ages about a blacksmith named Dunstan. Dunstan was visited by the devil in his blacksmith shop. The devil wanted Dunstan to make him shoes, but Dunstan refused and beat the devil, making him promise never to enter a place where a horseshoe hung over the door. To prevent luck from running out, the horseshoe must hang toe down.

Hmm, the blacksmith reference fits, but this horseshoe hangs toe-up. Also, I remember my daughter returning from horse camp with a horseshoe, and the assertion that it must be hung toe down as it held luck, and if it was upside down, the luck would run out.

After a good bit of searching, which elicited superstitions about how horseshoes over a stable door prevented witches from riding the horses furiously all night, how in Germany, finding a horseshoe is considered good luck, etc., etc., my eureka came at ‘The Lucky W’ Amulet Archive.

The use of worn-out horseshoes as magically protective amulets — especially hung above or next to doorways — originated in Europe, where one can still find them nailed onto houses, barns, and stables from Italy through Germany and up into Britain and Scandinavia. …

There is good reason to suppose that the crescent form of the horseshoe links the symbol to pagan Moon goddesses of ancient Europe such as Artemis and Diana, and that the protection invoked is that of the goddess herself, or, more particularly, of her sacred vulva. As such, the horseshoe is related to other magically protective doorway-goddesses, such as the Irish sheela-na-gig, and to lunar protectresses such as the Blessed Virgin Mary, who is often shown standing on a crescent moon and placed within a vulval mandorla or vesica pisces.

In most of Europe, the Middle-East, and Spanish-colonial Latin America protective horseshoes are placed in a downward facing or vulval position, as shown here, but in some parts of Ireland and Britain people believe that the shoes must be turned upward or “the luck will run out.” Americans of English and Irish descent prefer to display horseshoes upward; those of German, Austrian, Italian, Spanish, and Balkan descent generally hang them downward.

Hence, to the mid-nineteenth century eye, this sign on my ancestor’s shop also meant most likely a blacksmith of German descent hammered within.