Drawing by Hartley Ramsay, from “A Skinful of Scotch” by Clifford Hanley

When it comes to looking into history, “expect the unexpected” is my common refrain. Take Thanksgiving. Wasn’t that holiday always celebrated, since the birth of our nation, on the fourth Thursday of the month? Wrong. I’ve written a couple of posts on that, here (Thanksgiving Cockfights), and here (“We were not the Savages”).

Then there’s Christmas. While researching for my new novel set in part in the Highlands of Scotland, I’ve discovered that Scotland in the Reformation Era did not celebrate Christmas. Huh?! Weren’t they Presbyterians? Yes, in their own way. The Scots were most bitter toward Catholicism, and saw Christmas as a “Papist” holiday, hence, no yuletide cheer and feasting and presents. An article published in The Oldie, explains:

Things were done differently in Scotland. Our [Scottish] Reformation came to us from Geneva, and we drank the pure water of Calvinism. Anything that smacked of Papist idolatry was banned. Anything for which there was no scriptural authority was out of order. No celebration of Christmas, after the Nativity itself, is recorded in the Bible. Therefore there should be none in Scotland. Accordingly it was forbidden, along with the other feasts of the Roman Church.

Apart from anything, Christmas encouraged jollity, and jollity was suspect, feasting an invitation to sin. In any case the Presbyterian Kirk then, and for a long time after, paid little heed to ‘gentle Jesus, meek and mild’. [From “The Oldie” article, January 2016, “How Scotland Discovered Christmas”]

The subhead of The Oldie‘s article begins: “Children in Scotland used to wait till Hogmanay for their presents …” Hogmanay?!?! What the devil is that? Duh. Hogmanay is a New Year’s Eve custom that goes back hundreds, if not thousands, of years. And it’s … ahem … quite different than you might expect.

First of all, you don’t drink, at least not at first. Instead, you clean. That’s right, *clean.* It’s called “Redding the House.” Traditionally, Scots did not drink a drop on New Year’s Eve, but scoured the house top to bottom instead. That is, until the stroke of midnight, when the doorbell rings, a signal the new year is here with the arrival of the first foot, hopefully a tall dark and handsome one. First foot?! The custom goes like this:

“After the stroke of midnight, neighbors visit each other, bearing traditional symbolic gifts such as shortbread or black bun, a kind of fruit cake. The visitor, in turn, is offered a small whisky – a wee dram. … If you had a lot of friends, you’d be offered a great many wee drams. The first person to enter a house in the New Year, the first foot, could bring luck for the whole year to come. The luckiest was a tall, dark and handsome man. The unluckiest a redhead and the unluckiest of all a red-haired woman. And, in case you’re wondering why a red-haired woman is the unluckiest, just remember that Viking raiders first brought fair hair to Scotland. And if a Viking woman was first to enter, she would surely be followed by an angry Viking man. Whatever your gender or the color of your hair, don’t go first footing without a gift for your hosts …” by Ferne Arfin, from “5 Scottish Hogmanay Traditions You Probably Never Heard Of Celebrations, Fire Festivals and Hospitality Welcome the New Year”

Aye, a wee dram. Don’t mind if I do.

In the book A Skinful of Scotch (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965) author Clifford Hanley writes about Hogmanay with poignant hilarity.

“The Scots have always been early bedders and none of your night-club nonsense, [so Hogmanay] has always been the one night of all when the nation has a licence to be up turning night into day … In theory, this is the time when every Scotsman re-discovers his love for the whole of humanity, and the theory works well enough. What often makes Hogmanay memorable is the way our frail natures break down…” at which point Hanley follows up with a number of humorous examples. His final story is about the time he and friends celebrated Hogmanay at a ski lodge.

“An atmosphere of painful excitement burgeoned as the hours ticked away [to midnight], because the guests included a great mob of bright, healthy young schoolteachers from the North of England, spending their very first Hogmanay in the land that invented it. … Everything started on this quiet, reverential note [of producing bottles and ceremonially exchanging drinks], which is correct. As each member present insisted on a round from his bottle, the little group grew noisier and more creative. Athletic people, carried away with bonhomie, stood on their hands. Non-pianists tried a tune on the baby grand. Ancient tunes were dredged up from the collective unconscious. … And so, with many a song and frivolity, we were set to wheel the night away, when some of the keen young English teachers — all in their early twenties — came timidly through the door, and were welcomed in the true Hogmanay spirit by being offered a drink. Some of them didn’t take it, and a human being is entitled not to drink. But steeped in tradition as we were, we all noticed simultaneously that whether they drank or not, none of them had caught on to the infrangible rule that you bring a drink with you.”

Other traditions at Hogmanay, written and unwritten, endure, but in the spirit of ringing in 2021, I’ll mention just one more — the singing of “Auld Lang Syne.” That’s right, the song is Scotland’s own, the most well-known version written by Robert Burns.

Happy New Year!!

I had the good fortune this past month to be in London. On a visit to Westminster Abbey, this bell caught my eye, hanging near the grave of the unknown warrior. “HMS Verdun” brought to mind an inherited piece of jewelry, a gold cross that came to me on the death of my father’s cousin’s wife, May Patterson.

I had the good fortune this past month to be in London. On a visit to Westminster Abbey, this bell caught my eye, hanging near the grave of the unknown warrior. “HMS Verdun” brought to mind an inherited piece of jewelry, a gold cross that came to me on the death of my father’s cousin’s wife, May Patterson. “It’s a cross made from the wedding rings of her first marriage,” Dad said. “He died in WWI.”

“It’s a cross made from the wedding rings of her first marriage,” Dad said. “He died in WWI.”

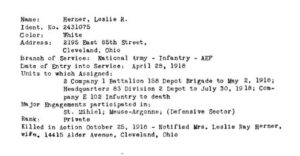

Leslie was 29 years old at the time of his death. May turned 29 a month later. Thirteen years later, she married again but remain childless. She outlived her first husband by 58 years. Leslie Ray Herner is not an “unknown warrior.” His cross stands in the graveyard of the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial. Still, it feels important to remember, albeit 105 years later, their sacrifice and loss, like that of so many other unsung heroes.

Leslie was 29 years old at the time of his death. May turned 29 a month later. Thirteen years later, she married again but remain childless. She outlived her first husband by 58 years. Leslie Ray Herner is not an “unknown warrior.” His cross stands in the graveyard of the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial. Still, it feels important to remember, albeit 105 years later, their sacrifice and loss, like that of so many other unsung heroes.