Yesterday afternoon, the European Soccer Championship quarterfinal between Germany and Italy was tough going. My son was home, watching it about two feet away from the screen because he didn’t have his contacts in.

“I wonder about the history of soccer,” I said from back on the couch like a normal person.

“It started in England,” he said, spooning breakfast cereal into his mouth. “They call it football, but ‘socc’ was the nickname for the association, and they added the ‘-er’ on the end.”

Huh. This morning, still bemoaning Germany’s heartbreaking loss, I began clicking around for more enlightenment. The research trail was labyrinthine, since the keywords “history of soccer” and “history of football” are interchangable in certain corners of the world. Still, I found the basics quickly: games where a ball is kicked by the foot date back to China 1700 years ago etc. etc. Fast forward to 1863, when two English Football Associations were founded: Association (“Socc-er”) Football and Rugby Football (the former being a game where the ball could not be touched by the hands).

Still, confusion reigned. For instance, in the Gale Cengage 19th Century U.S. Newspapers database, I found no mention of the word “soccer,” but “football” turned up the following.

Boston Daily Advertiser (Boston, MA) Thursday, January 14, 1864

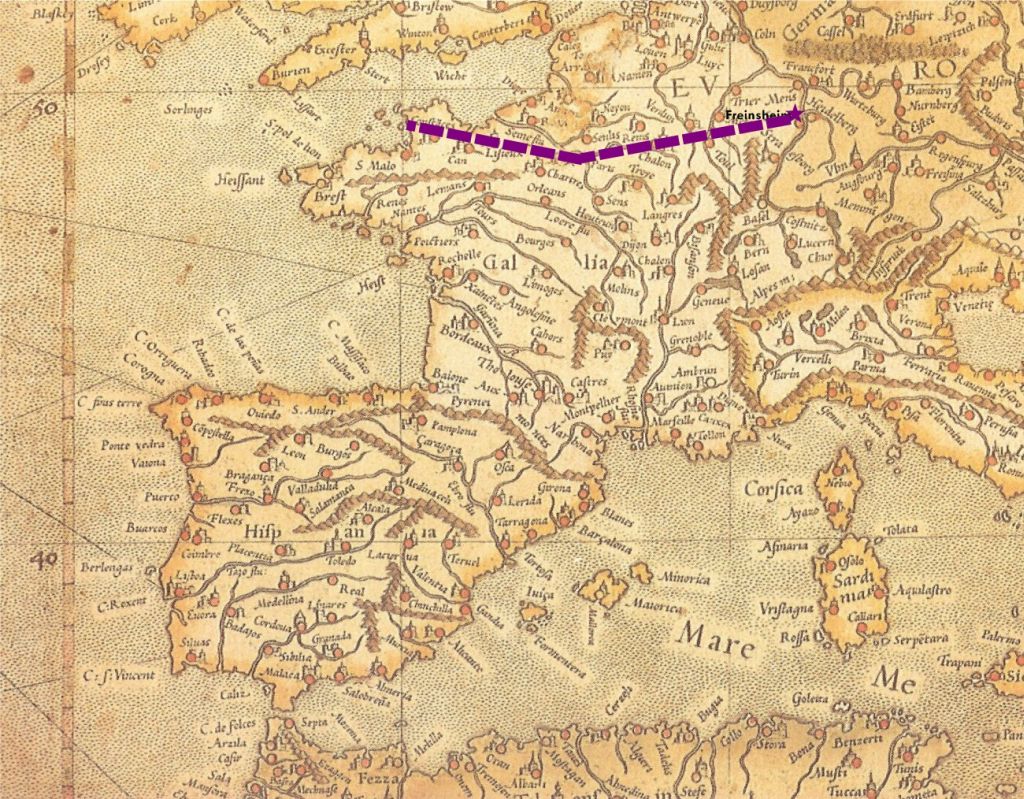

“A number of English gentlemen living in Paris have lately organised a football club, to which is to be added athletic indoor exercises of a gymnasia character. The football contests take place in the Bois de Boulogne, with the permission of the French authorities, and surprise the French amazingly.”

Hmm. Do they mean socc-er? Or rugg-er? (British nickname back then for rugby.) Interesting that the Boston Daily Advertiser is reporting the goings-on in Paris. Over a decade later, the same newspaper reports on a football match in Cambridge, Mass. between Harvard and Canada (Tuesday, May 09, 1876). The “Harvards” won, 1-0. But descriptions of the goals and touchdowns, movement up and down the field, etc. more closely resemble rugby.

Meanwhile, Germany did not found a football (soccer) association until 1900, one of the last countries in Europe to do so. One reason might be that, unlike the rest of western Europe, Germany was not a country until 1871. Early on, a memorable, crushing defeat for Germany occurred in 1909, when England trounced Germany 9-0. In the latter half of the 20th century (after two world wars, and decades where Germany was divided into two countries, then reunited), Germany had a string of victories, prompting Gary Lineker, England’s legendary striker, to state (after England’s 1990 World Cup loss): “Soccer is a game for 22 people that run around, play the ball, and one referee who makes a slew of mistakes, and in the end Germany always wins.”

A more complete exploration of 20th century German soccer can be found at Soccer-Fans-Info.com.