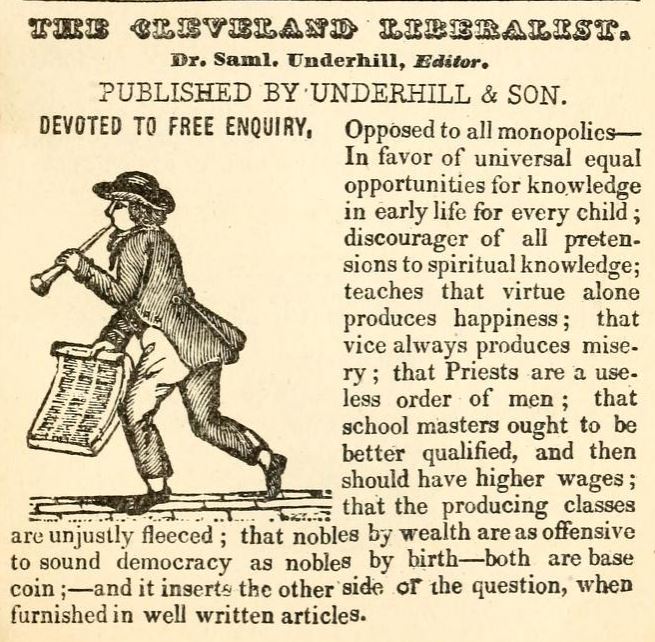

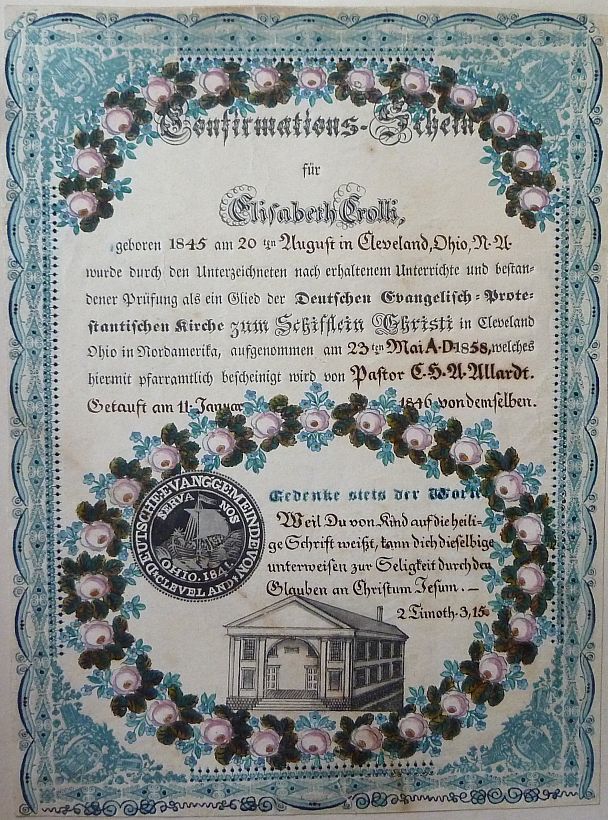

I have a copy of the compendious Jubilee Edition of the Cleveland Wächter und Anzeiger 1902 — a 50th anniversary edition of items published in the Cleveland German newspaper of that name. Since the Jubilee edition was written in German, it languished in relative obscurity for almost 100 years, until an English translation appeared in the year 2000, a publication of Cleveland’s Western Reserve Historical Society. I am forever indebted to WRHS for this translation. I turned to it countless times during my research for The Last of the Blacksmiths.

I have a copy of the compendious Jubilee Edition of the Cleveland Wächter und Anzeiger 1902 — a 50th anniversary edition of items published in the Cleveland German newspaper of that name. Since the Jubilee edition was written in German, it languished in relative obscurity for almost 100 years, until an English translation appeared in the year 2000, a publication of Cleveland’s Western Reserve Historical Society. I am forever indebted to WRHS for this translation. I turned to it countless times during my research for The Last of the Blacksmiths.

Chock full of information about German immigrants to Cleveland (until the year 1902), the compilation of German newspaper items includes a brief write-up on the then-fledgling automobile industry.

“The first American vehicle was manufactured in Cleveland” the heading on p. 98 proclaims. (In reality, this turns out to be incorrect. According to an interpretive display at the Western Reserve Historical Society Crawford Auto Aviation Collection, the Duryea, “built by brothers Charles F. and J. Frank. Duryea, is often credited as being the first American automobile making its public appearance in 1893 in Springfield, Massachusetts.”)

Anyhow, the Jubilee goes on, “Alexander Winton, the pioneer of the industry in America, was the first manufacturer of this sort of machine.” A Scottish immigrant who originally made bicycles, Winton sold 100 of these one-cylinder gas-powered vehicles in 1898.

Anyhow, the Jubilee goes on, “Alexander Winton, the pioneer of the industry in America, was the first manufacturer of this sort of machine.” A Scottish immigrant who originally made bicycles, Winton sold 100 of these one-cylinder gas-powered vehicles in 1898.

[Pictured left: a Winton Buggy circa 1899. This and all photos below were taken during my visit to the Crawford Auto Aviation Collection at the Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland, Ohio.]

“The steam motor is manufactured by the White Sewing Machine Company, which has given up the manufacture of bicycles and produced an automobile powered by a combination of gasoline and steam. The machine has won all competitions it has entered.” —Jubilee, p.98

“The steam motor is manufactured by the White Sewing Machine Company, which has given up the manufacture of bicycles and produced an automobile powered by a combination of gasoline and steam. The machine has won all competitions it has entered.” —Jubilee, p.98

[Pictured left: a 1902 White Motor Car]

The White Sewing Machine Company of Cleveland was a successful business founded by Thomas White. However, White’s sons had their eyes on the young automobile industry. They convinced their father to allow them to begin producing autos. … Relying on the innovative “semi-flash boiler” developed by Rollin White, the company became successful with steam-powered vehicles. White steamers were the best on the market in the days when it was still not standard for autos to be powered by internal combustion engines. White steamers raced and set speed records. When Theodore Roosevelt took the wheel of a White steamer, he became the first U.S. president to drive an automobile. — Interpretive display at Western Reserve Historical Society Crawford Auto Aviation Collection, Cleveland Ohio

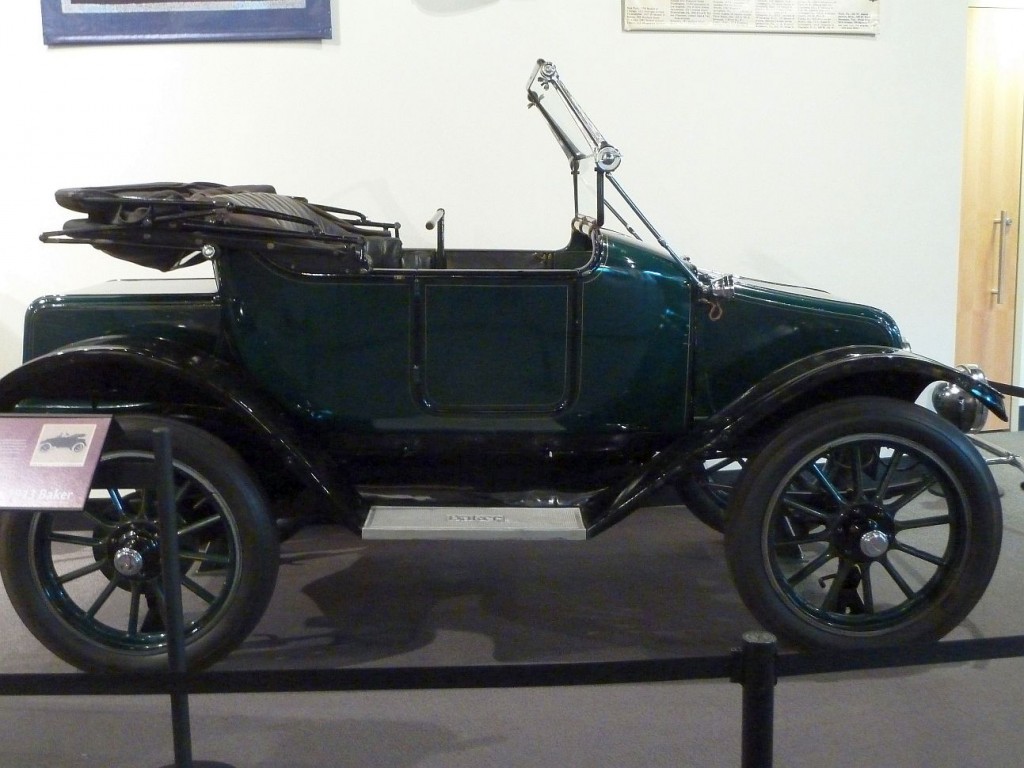

“The electric automobile manufactured by the Baker Motor Vehicle Company, enjoys a positive reputation. This sort of vehicle is not suited for long trips, but rather for use in the city or in the suburbs.”

“The electric automobile manufactured by the Baker Motor Vehicle Company, enjoys a positive reputation. This sort of vehicle is not suited for long trips, but rather for use in the city or in the suburbs.”

–excerpt of an interpretive display at Crawford Auto Aviation Collection

[Pictured right: a 1904 Baker Electric]

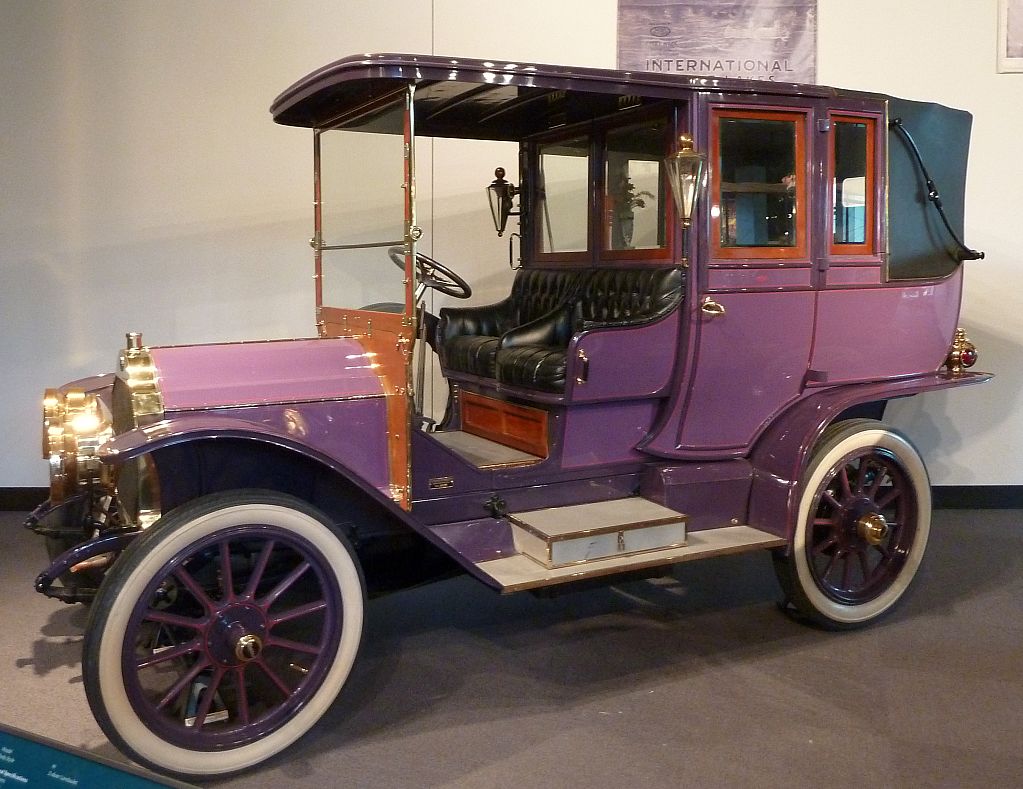

Another electric auto maker in Cleveland was the Rauch & Lang electric. Why wouldn’t the German newspaper be touting a German automaker? Because the first Rauch & Lang vehicle would not come out until 1905.

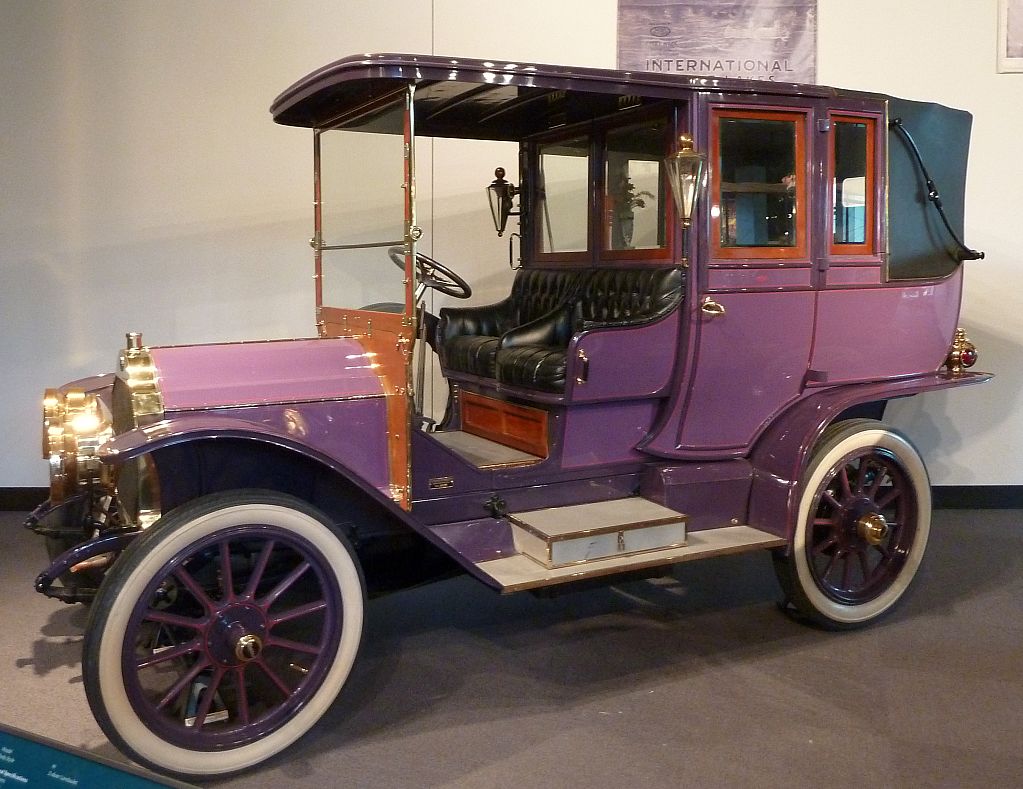

[Pictured left: a 1916 Rauch & Lang.]

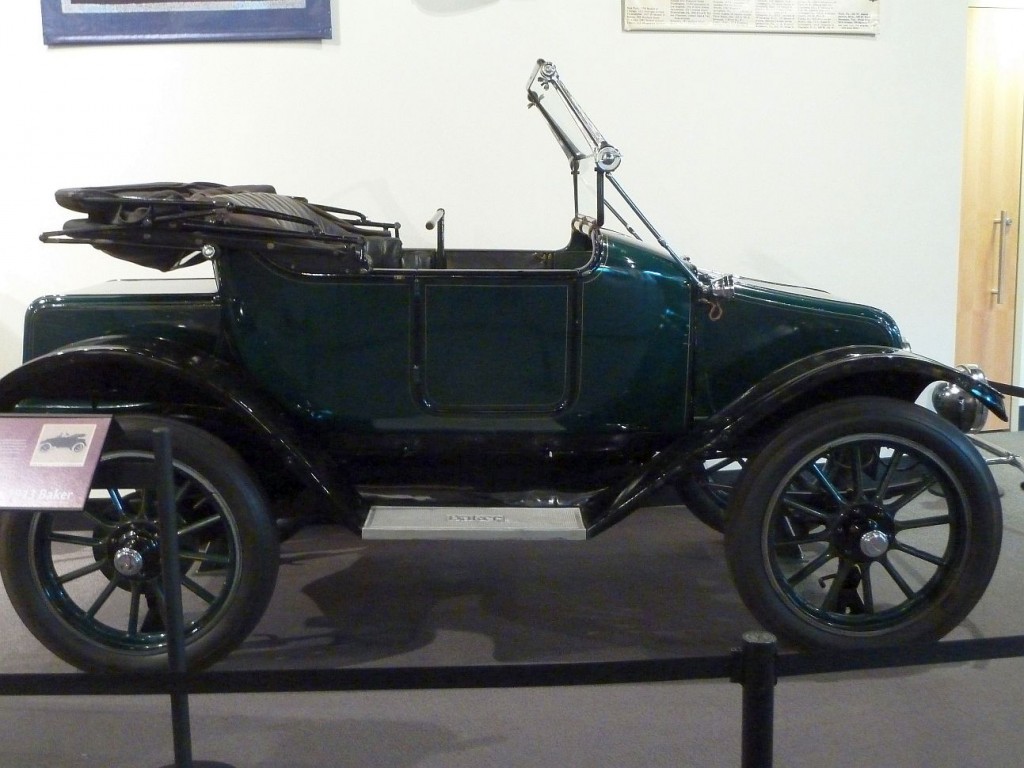

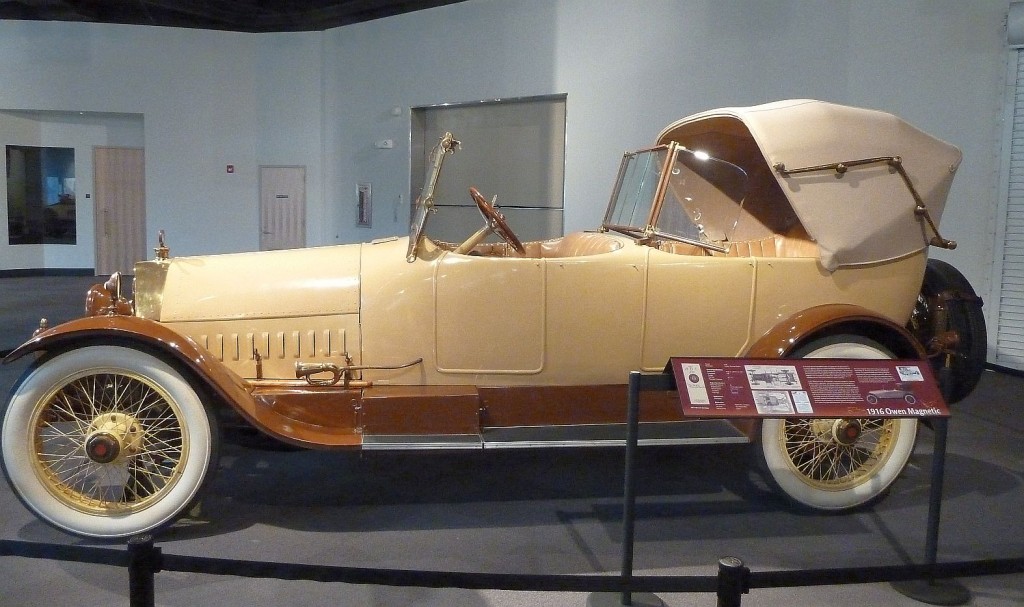

Just a few years beyond 1902, automobiles would quickly blossom from their horse-drawn buggy origins to sleek, luxurious rides. Below are more examples from the tremendous exhibit at the Crawford Auto Aviation Collection in Cleveland.

The White Motor Company Model D from 1904

This Baker electric model is from 1913, a time when gasoline-powered vehicles were finally beginning to dominate the automobile market.

A 1907 Studebaker-Garford, built in Elyria, Ohio, most popular with women drivers. (The Studebaker Company was located in South Bend, Indiana, but contracted out the production of automobiles in this era.)

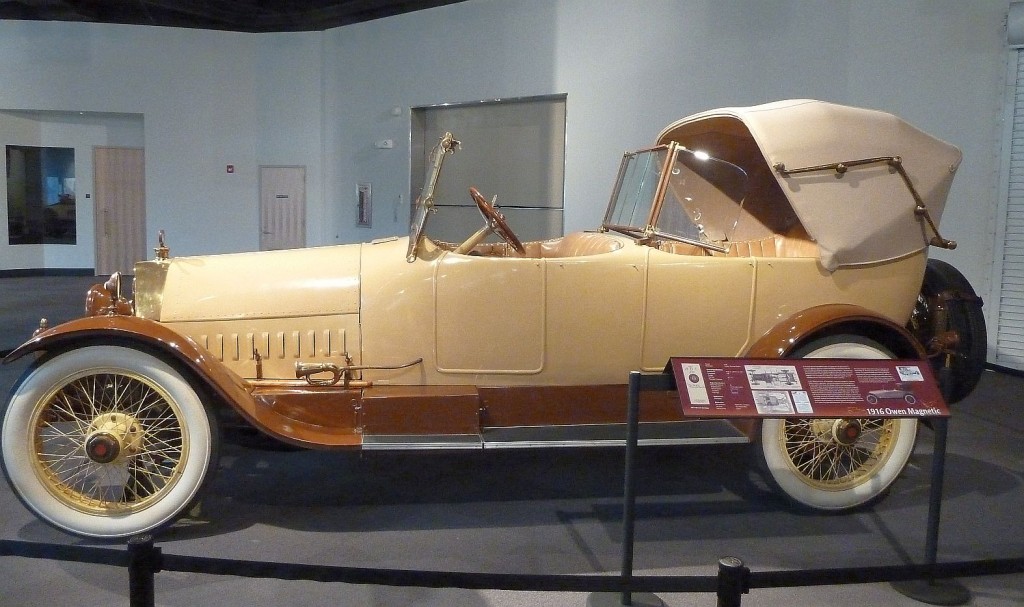

A 1916 Owen Magnetic. Baker attempted to combine the smooth electric ride and power of gasoline in this car. Just a year before, Baker Electric had merged companies with Rauch & Lang and the R.M. Owen company as well.