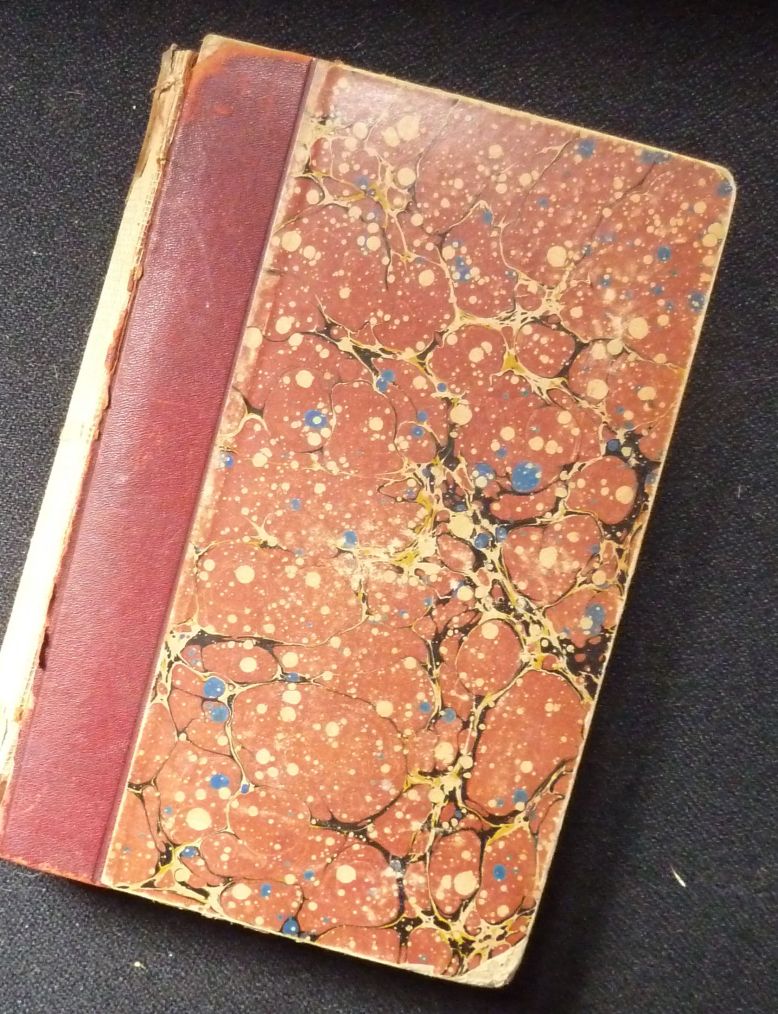

I stopped by an estate sale yesterday and, as always, rummaged through the box of books. Usually by Saturday afternoon all the treasures are long gone. But this 1876 copy of The Deerslayer by James Fenimore Cooper, with its crumbling spine, lay overlooked. The seller wanted fifty cents.

I stopped by an estate sale yesterday and, as always, rummaged through the box of books. Usually by Saturday afternoon all the treasures are long gone. But this 1876 copy of The Deerslayer by James Fenimore Cooper, with its crumbling spine, lay overlooked. The seller wanted fifty cents.

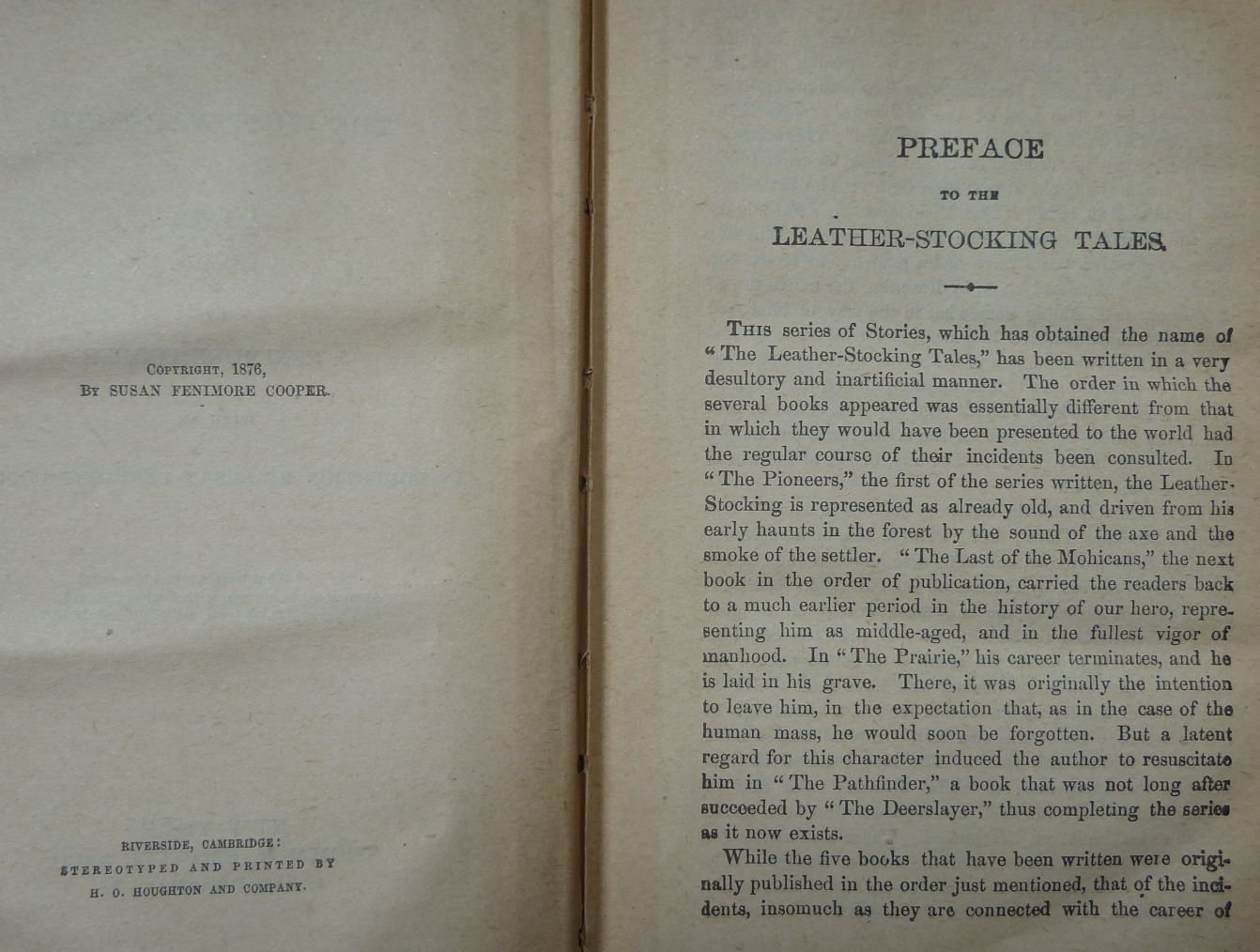

Chronologically the first in the series of Cooper’s five “Leather-Stocking Tales,” The Deerslayer was published last, in 1841. What I love about this 1876 edition is that Susan Fenimore Cooper, the author’s daughter, holds the copyright and supplies her own “Introduction” about the history, the geography, flora and fauna of the Lake Otsego region. According to Quotidiana, “Susan Fenimore Cooper is remembered as America’s first female nature writer,”  best known for her nature journal Rural Hours. She also worked for female suffrage, wrote articles for magazines, helped her father edit his books, and was so essential to his life he disapproved her several suitors and she never married.

best known for her nature journal Rural Hours. She also worked for female suffrage, wrote articles for magazines, helped her father edit his books, and was so essential to his life he disapproved her several suitors and she never married.

Browsing through her “Introduction,” I found the following:

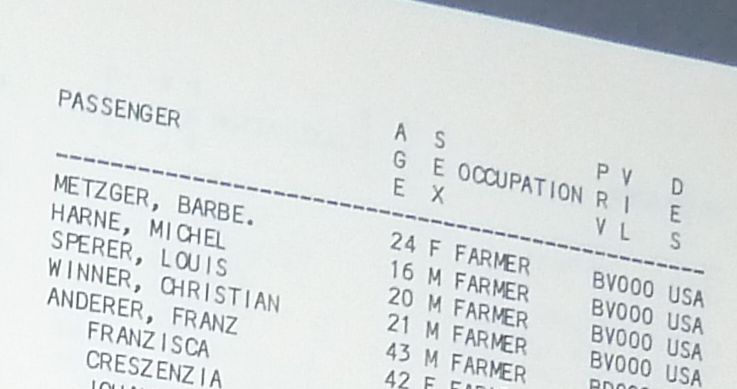

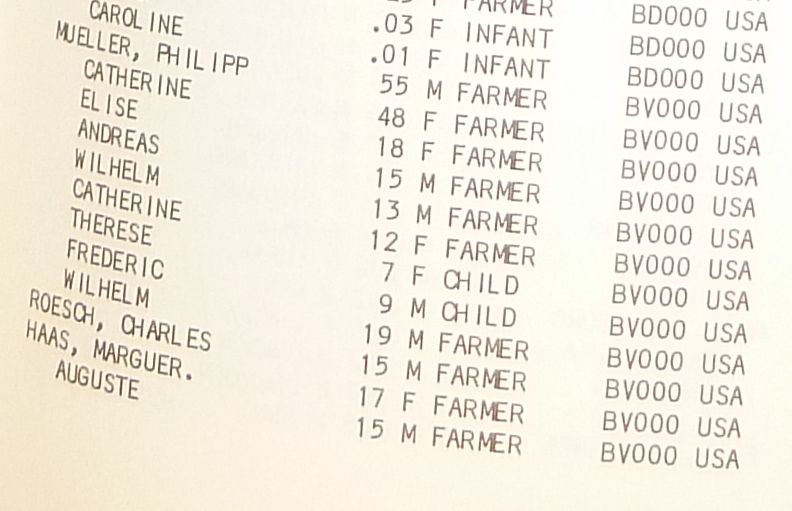

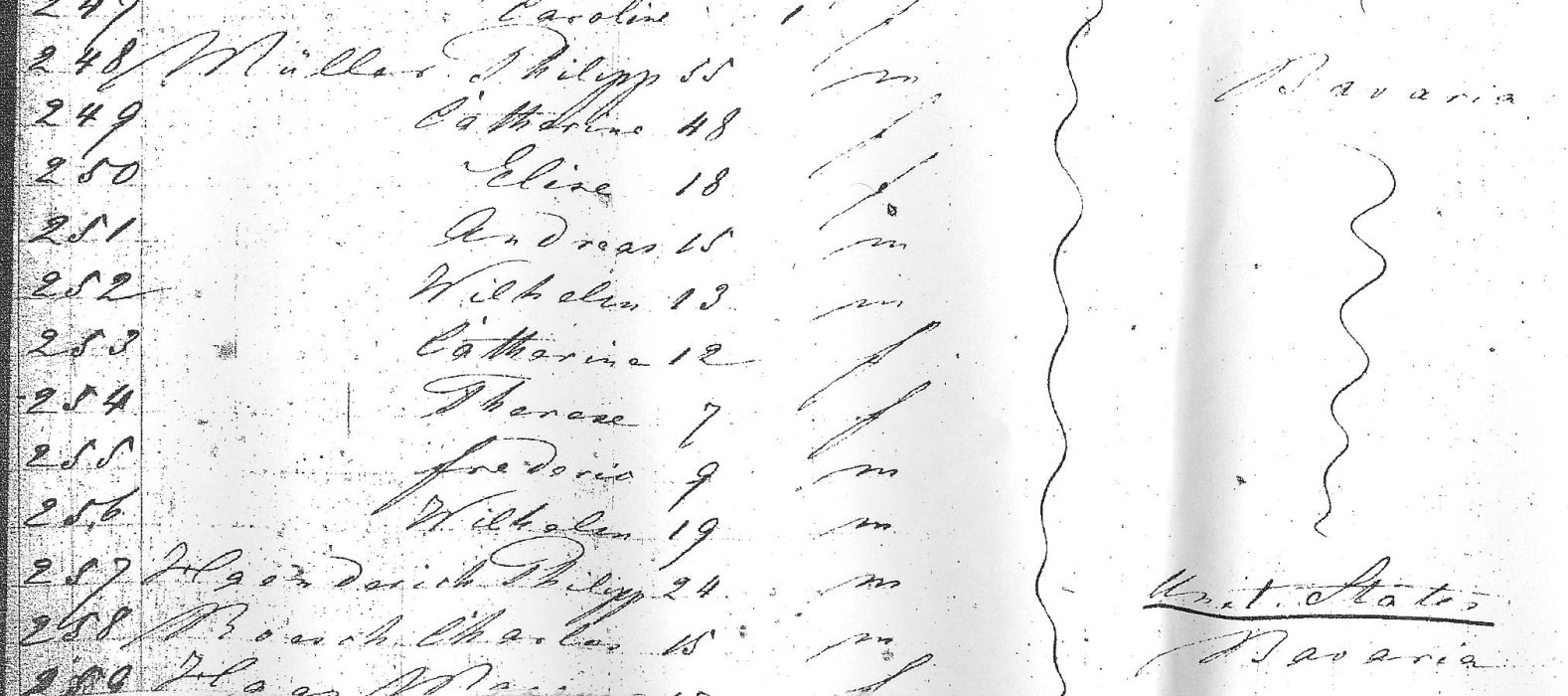

“In the year 1709 a large party of Protestant Germans from the Palatinate, fleeing from the effects of religious persecution, and the poverty brought upon Rhenish Germany by the wars of Louis XIV., emigrated to America under the patronage of Queen Anne. Some three thousand crossed the Atlantic at this period. Many of these settled in Pennsylvania, others on the Hudson, others at the German Flats on the Mohawk. A colony of several hundred of these worthy industrious people settled on the banks of the Schoharie [New York] in 1711. … Natty [hero of “The Leather-Stocking Tales”] and Hurry Harry are supposed to have approached [Lake Otsego] from the little colony on the Schoharie, founded thirty years earlier by the ‘Palatines,’ as they were called.

“There was a village of the Mohegans on the Schoharie, at the foot of a hill called by them ‘Mohegonter,’ or ‘the falling away of the Mohegan Hill.’ These Mohegans came, it is said, originally from the eastward, beyond the Hudson. The clan is reported to have numbered some three hundred warrieors when the Germans arrived among them. A tortoise and a serpent were the tokens of this clan. documents, chiefly sales of land to the Germans, still exist bearing their signatures in this shape.”

There is much more, about how her father decided to write The Deerslayer, about the end of her father’s days in Cooperstown, NY. Not to mention my delight at stumbling upon such a treasure.