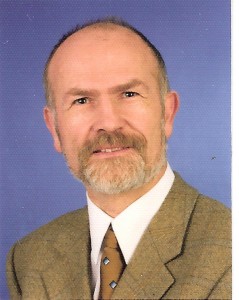

Recently, after a few years of email correspondence with Palatinate historian Dr. Hans-Helmut Görtz, I drew up the courage to ask him to review my completed manuscript Harm’s Way: A Blacksmith’s Journey for historical accuracy, in light of the fact I will send it soon to a publisher.

Dr. Görtz answered almost immediately in the affirmative, adding:

“Harm’s Way – what a coincidence! A very short time ago I read a very touching book Out of Harm’s Way. The British author Jessica Mann (British crime writer and herself a war-time evacuee) … describes the fate of thousands of children sent overseas when the threat of a German invasion in England was imminent. Jessica’s grandfather Richard Mann, who in 1938 settled in Oxford, was a friend of Hermann Sinsheimer [a native of Freinsheim] and is mentioned in Sinsheimer’s letters to Frida Schaffner née Reibold. Together with Erik and Gabriele Giersberg, I have edited these Sinsheimer letters in a comprehensive book Briefe aus England in die Pfalz which came out only recently. But finally let’s come to your question. Of course I will support you as far as I can …”

Help me he did. As we have continued our email exchange, it occurred to me others will benefit from Dr. Görtz’s extensive knowledge, writings about history (a comprehensive list of his publications follows this interview), and insights about the Palatinate region he calls home.

INTERVIEW WITH DR. HANS-HELMUT GÖRTZ

INTERVIEW WITH DR. HANS-HELMUT GÖRTZ

For a number of years, Dr. Görtz, you have been a scholar of the history of the Palatinate. What is especially intriguing to you about this region?

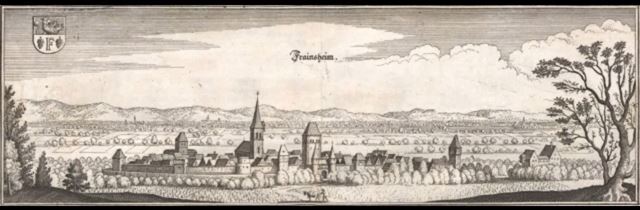

Since 1983 I have lived with my family in Freinsheim. From the beginning on – as it is a tradition in my family – I was an active member in the Freinsheim Catholic community (a member of the parish council, a member of the parish administration council). In 1995, we decided to make a restoration of the historical organ (installed in 1825) in the Freinsheim Catholic church. I took responsibility to set up a Festschrift to be presented at the re-inauguration ceremony of the organ. For that purpose, for the first time I studied a little bit about the history of the Catholic community in Freinsheim during the 18th and 19th centuries, and I was quite fascinated. For me it was the starting point for an intensive and deep preoccupation with the history of Freinsheim and its environs. Since that time I published 4 books and about 35 papers in historical journals and have given a couple of slide lectures in Freinsheim, Mannheim and Heidelberg.

According to your internet bio (link here), you originally studied ancient languages, then went on to do graduate work in chemistry. What made you return to a study of history?

To avoid any misunderstanding: After elementary school, I attended a so-called “Altsprachliches Gymnasium,” a secondary school where we learned the ancient languages Latin and Greek and the modern language French (not English ! I never learned that formally in any school !). But at this school we also had an excellent education in mathematics and sciences. After the Abitur (final exam) I decided to study chemistry (a good choice !) doing my studies at the universities of Mainz, Freiburg and Ulm. After having finished my Ph.D. thesis in Ulm I joined BASF polymer research in Ludwigshafen in 1981 and worked there until my retirement in 2012.

It appears you follow in the footsteps of your grandfather, who was also a historian?

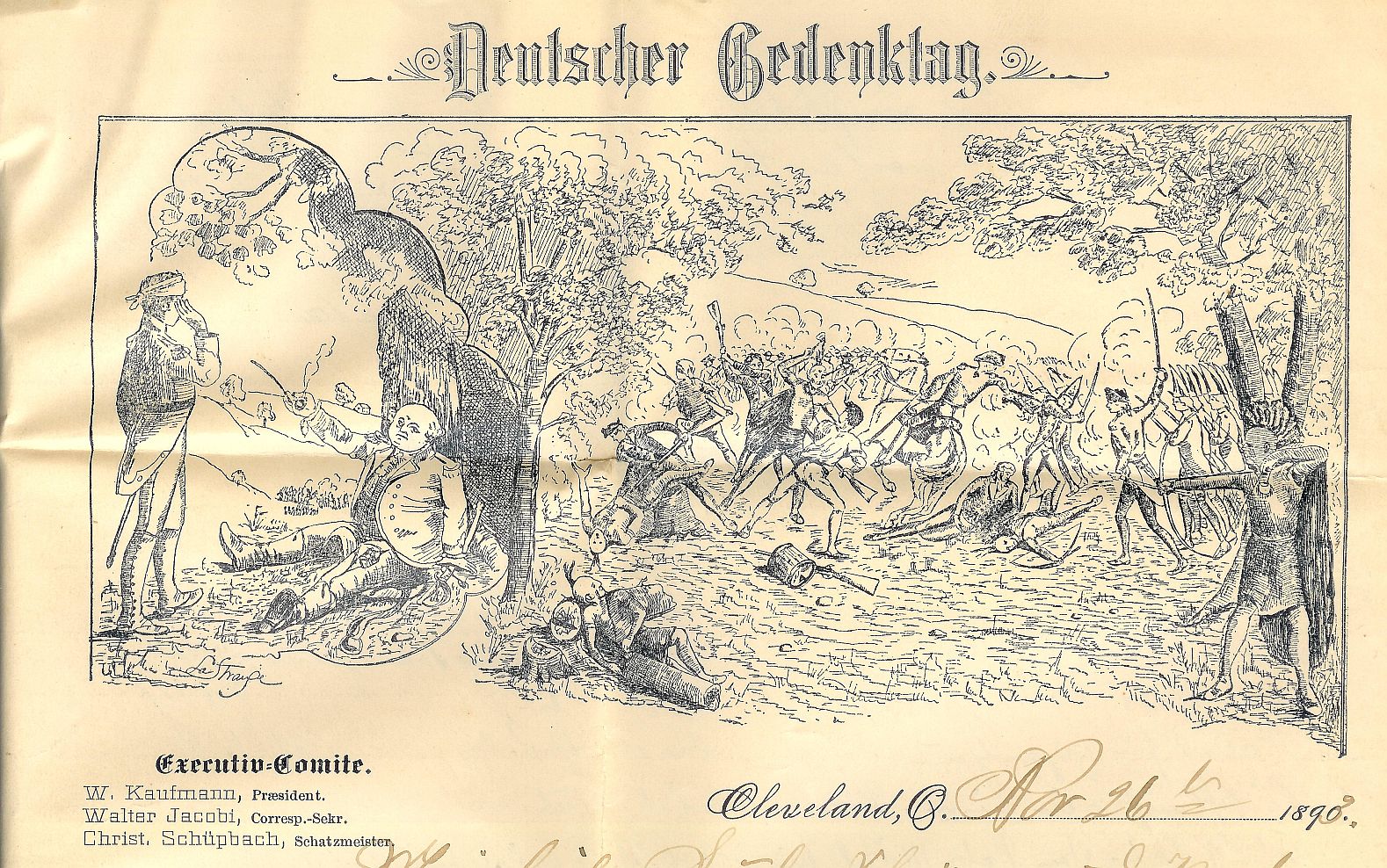

My grandfather Joseph Görtz, who unfortunately died in the age of 46 in 1934, was a teacher at the elementary school in Venningen and later on in Edenkoben in the southern Palatinate. He was very interested in history and wrote a remarkable booklet about the combat around the so-called “Schänzel” near Edenkoben during the invasion of French troups in 1794-95. He also left a manuscript on the history of the village Venningen, which has been edited decades later by my father Hugo Görtz. My father himself, a tax inspector, after his retirement spent a lot of time (together with my mother Marga) researching our ancestors. The result of their work is an elaborate book “Unsere Ahnen” in three handwritten and hand-drawn copies for my two sisters and me.

The town of your birth, Edenkoben, is the seat of the Schloss Villa Ludwigshöhe. Did this offer an early influence for your love of history?

Perhaps you also could observe that young people have little or no interest in history, but my experience is that, with increasing age the interest in history also increases. Such is the case for me. In my youth I had no special interest in history. My memories of Villa Ludwigshöhe are very simple: Villa Ludwigshöhe is situated at the eastern border of the Pfälzerwald, this border consisting of chestnut trees. So my memory is walking there every fall with my grandmother to collect chestnuts to sell to a local grocery – a very welcome revenue for a boy in the late 1950s/early 1960s.

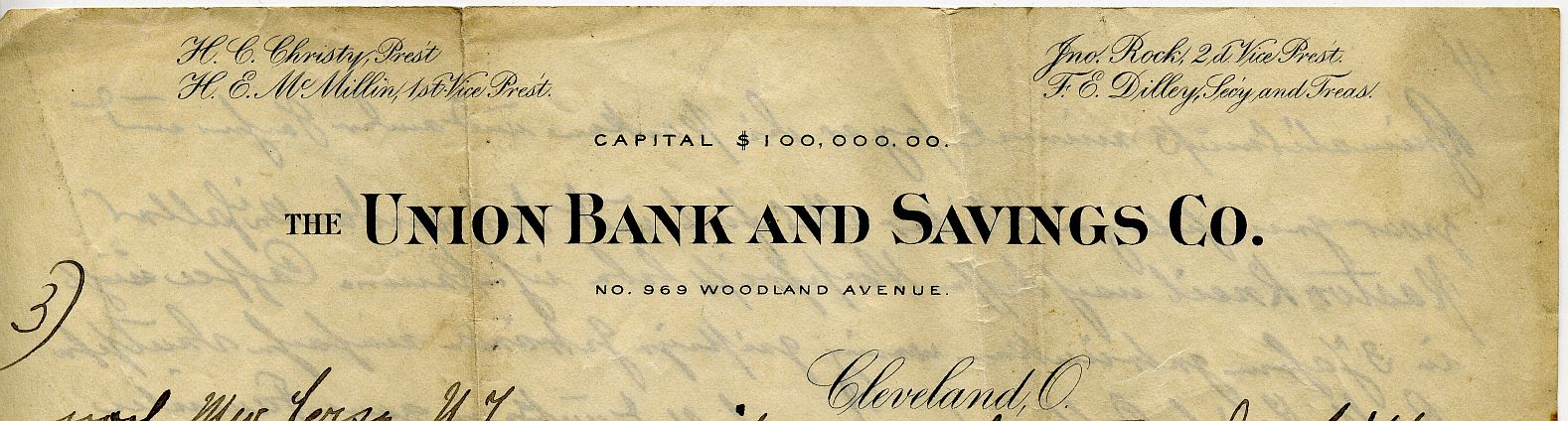

You must be a frequent visitor to the Palatinate archives at Speyer. Do you have any advice to genealogy researchers, for how to navigate the search for their ancestors at this archives and others in the region?

I have been in many archives, not only in Speyer, but frankly, I don’t feel too comfortable with your question, since genealogy is not my main area of study. So I would like to avoid your question a little bit by saying that there are genealogical societies with much knowledge and expertise, which it would be very worthwhile to contact. The corresponding society for our region is the Pfälzisch-Rheinische Familienkunde with a very useful library located in Ludwigshafen/Rhein.

Regarding the book Briefe aus England in die Pfalz, released at the end of 2012, which you co-authored to publish the letters of the Sinsheimer family. The writer and journalist, critic and lawyer Hermann Sinsheimer was a native to Freinsheim, and wrote about the city, did he not?

Hermann Sinsheimer (1883-1950) was born in Freinsheim. A lawyer by training, after practicing only a few years he abandoned his profession for theater, his true passion. Living in Munich in the years 1916 to 1929, he was a director of the Kammerspiele, chief editor of the satirical magazine Simplicissimus, feature writer and critic of Münchner Neueste Nachrichten. In 1929 he moved to Berlin, were he worked for the Berliner Tageblatt. Since Sinsheimer was Jewish, in the advent of the Nazi terror in 1938, he fled to England. He died in London in 1950. From 1946 until his death, Sinsheimer wrote numerous letters to his former Freinsheim schoolmate Dr. Frida Schaffner née Reibold. These letters as well as letters of his widow to the same addressee are the core of the book you are asking about. You see – the authors are Hermann Sinsheimer and his wife Christobel – not me and my colleagues. Nevertheless we have added an extensive introduction providing a lot of material and photographs about Sinsheimers ancestors, his brothers and sisters, his first wife and his second English wife Christobel and also about the living descendants of Sinsheimer’s sister in America. The book (768 p., hardcover, many photographs) is edited by the Stiftung zur Förderung der Pfälzischen Geschichtsforschung in Neustadt an der Weinstraße. It costs 49 Euros. Whoever is interested in buying a copy should just send me an email at hhgoertz@t-online.de. The foundation will send it on their account.

Is there anything I should be asking, that might be of interest to genealogists and scholars of the Palatinate?

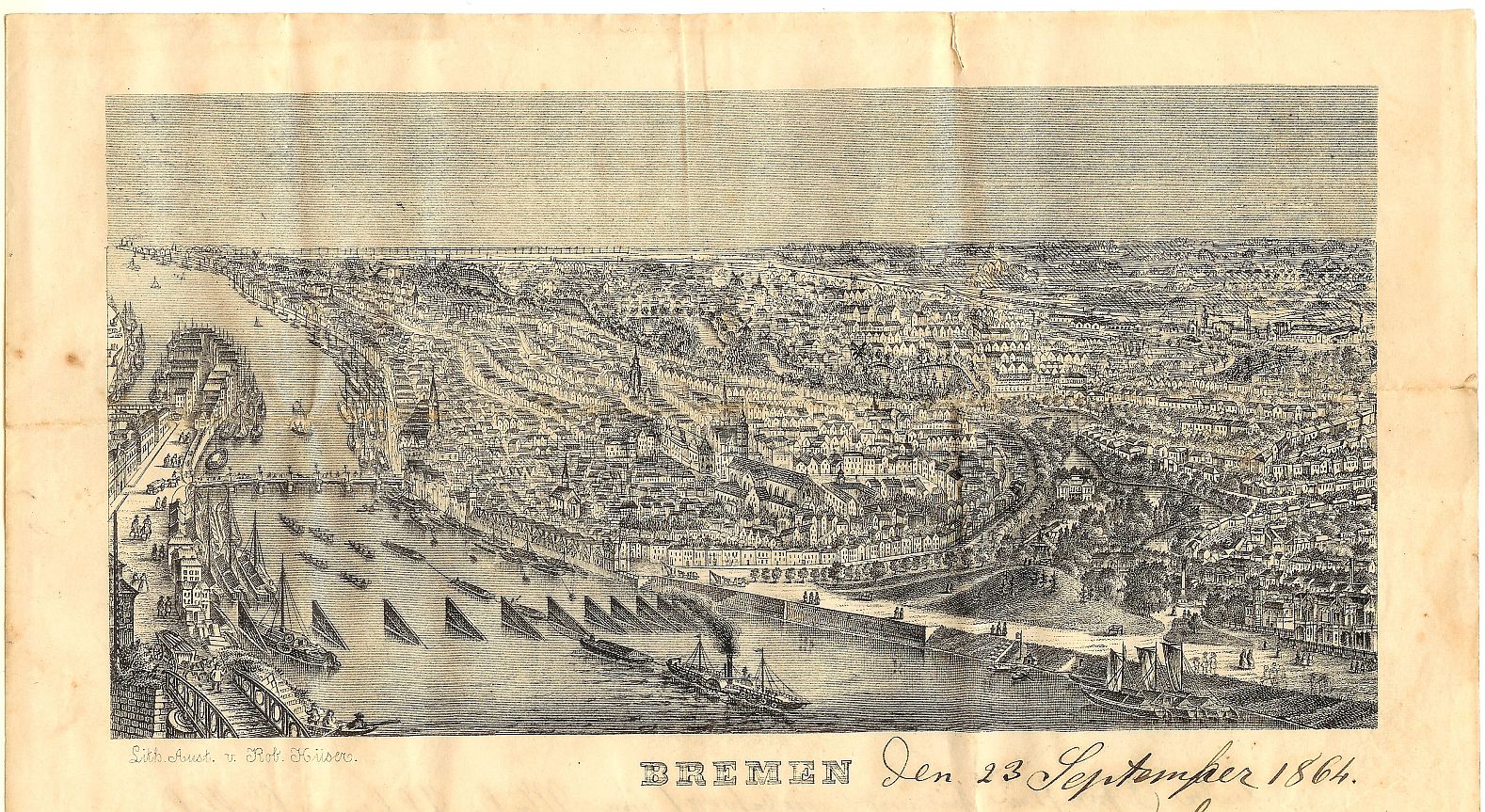

The history of the Palatinate is fascinating and nearly inexhaustible. For me the fascination is based on its historical diversity and lack of homogeneity: our small region was ruled by a lot of parallel rulers with their own territories: the prince electors of Palatinate, the counts of Leiningen, the bishops of Worms, the bishops of Speyer and so on … But not only diversity of lordship but also diversity in religion/confession: Reformed, Lutherans, Catholics, Mennonites, Jews …. last but not least: France …. we are close neighbors to France and remember: all the time before 1870/71 the invasions were from west to east, which the Palatinate had to suffer. The Palatinate region also benefitted from France, for instance with the introduction of the Code Napoleon, the Civil Code which remained in existence even after the French occupation ended.

Thanks so much, Dr. Görtz.

Dr. Hans-Helmut Görtz can be reached at

Am Wurmberg 11

67251 Freinsheim

Tel. 49 (0) 6353-7189

e-mail hhgoertz@t-online.de

Books and Booklets by Dr. Hans-Helmut Görtz

Festschrift zur Orgelweihe der restaurierten Seuffert-Orgel in der Pfarrkirche St. Peter und Paul Freinsheim, Freinsheim 1996, paperback, 108 p.

Das Freinsheimer Gottfried-Weber-Haus und seine Besitzer in kurpfälzischer Zeit, Sonderdruck, Freinsheim 2004 (offprint of identic paper from 2003 with some additions), paperback, 40 p.

Der kurpfälzische Vizekanzler Johann Bartholomäus von Busch (1680-1739) und seine Familie, Freinsheim 2005, paperback, 136 p.

Das kurpfälzische Amt Freinsheim – Entstehung, Personal, Amtsbeschreibung, Freinsheim 2005(reprint of identical paper from 2005), paperback, 72 p.

Das Kallstadter Gerichtsprotokollbuch 1533-1563, Stiftung zur Förderung der Pfälzischen Geschichtsforschung, Reihe A, Bd. 6, Neustadt a. d. Weinstr. 2005, LXXX, 328 p.

Das Kallstadter Gerichtsprotokollbuch 1563-1740, Stiftung zur Förderung der Pfälzischen Geschichtsforschung, Reihe A, Bd. 7, Neustadt a. d. Weinstr. 2010, CXL, 899 p.

Mit Köpf(ch)en durch Freinsheim

Brochure with coloured illustrations, Freinsheim 2012, 16 p.

Hans-Helmut Görtz, Gabriele Giersberg und Erik Giersberg

Hermann und Christobel Sinsheimer, Briefe aus England in die Pfalz

Stiftung zur Förderung der Pfälzischen Geschichtsforschung, Reihe E, Bd. 1, Neustadt a. d. Weinstr. 2012, XI, 752 p.

Papers

“Zur Veränderung der Einwohnerschaft von Freinsheim in der zweiten Hälfte des 17. Jahrhunderts,” Pfälzisch-Rheinische Familienkunde 15 (2002), 129-136.

“Ausländische Zuwanderer 1650-1710 im reformierten Kirchenbuch von Weisenheim am Sand,” Pfälzisch-Rheinische Familienkunde 15 (2002), 137-140.

“Zum Taufnamen von Gottfried Jakob Weber, Mitteilungen der Arbeitsgemeinschaft” für mittelrheinische Musikgeschichte 76/77 (2003) 387-389.

“Das Freinsheimer Gottfried-Weber-Haus und seine Besitzer in kurpfälzischer Zeit,” Mitteilungen des Historischen Vereins der Pfalz 101 (2003), 173-210.

“Das Freinsheimer Kirchenzinsregister von 1658 und das Freinsheimer Almosenregister von 1700-1702 als personengeschichtliche Quellen,” Pfälzisch-Rheinische Familienkunde 15 (2003), 195-200.

“Dorf – Flecken – Stadt. Anmerkungen zum Status von Freinsheim bis zum Ende der Kurpfalz,” Pfälzer Heimat 55 (2004), 42-49.

Die Nagel’sche Erbteilung vom 27. Mai 1574 als Quelle für Freinsheimer Namen, Pfälzisch-Rheinische Familienkunde 15 (2004), 418-420.

“Juden im kurpfälzischen Freinsheim – eine Spurensuche,” Mitteilungen des Historischen Vereins der Pfalz 102 (2004), 139-155.

“Das Rittergeschlecht Nagel von Dirmstein, in: Michael Martin (Hg.), Dirmstein – Adel, Bauern, Bürger.” Stiftung zur Förderung der Pfälzischen Geschichtsforschung, Reihe B, Band 6. Neustadt an der Weinstraße 2005, S. 83-118.

“Das kurpfälzische Amt Freinsheim – Entstehung, Personal, Amtsbeschreibung,” Mitteilungen des Historischen Vereins der Pfalz 103 (2005), 243-312.

“Kurpfalz 1690er Jahre: Führungspersonal gesucht – Hauptsache Katholiken. Zur Herkunft der Familien Gobin, Müssig, Lippe, Morass.” Mannheimer Geschichtsblätter. Neue Folge 12 (2006), 73-94.

“Vom Eichsfelder Jesuitenschüler zum kurpfälzischen Vizekanzler: Johann Bartholomäus von Busch (1680-1739).” Eichsfeld-Jahrbuch 14 (2006), 141-151.

Die Stadtdirektoren des 18. Jahrhunderts. In: Ulrich Nieß und Michael Caroli (Hrsg.), Geschichte der Stadt Mannheim, Bd. 1, 1607-1801, Ubstadt-Weiher 2007, S. 309-310.

“Personen ausländischer Herkunft im lutherischen Kirchenbuch Kallstadt 1656-1739,” Pfälzisch-Rheinische Familienkunde 16 (2007), 296-302.

“Von Menschen und Büchern – Prozessakten erzählen über den Flecken Freinsheim vor 1600,” Pfälzisch-Rheinische Familienkunde 16 (2008), 393-400.

“Juden im Herxheimer Gerichtsprotokoll (1780-1818),” Pfälzisch-Rheinische Familienkunde 16 (2008), 433-442.

“Refugium Freinsheim: Der Dichter Julius Wilhelm Zincgref (1591-1635) und der Verleger Nikolaus von Pierron (1707-1760).” Heimat-Jahrbuch 2009 des Landkreises Bad Dürkheim, Haßloch 2008, S. 88-93.

“Johann Bernhard von Ehm und die Schlacht vor Freinsheim im Jahr 1638.” Mitteilungen des Historischen Vereins der Pfalz 106 (2008), 337-351

“Portraits in München aufgetaucht: Nikolaus von Pierron – ein Name bekommt Gesicht.”

Heimat-Jahrbuch 2010 des Landkreises Bad Dürkheim, Haßloch 2009, S. 200-201.

“Reisenpforte und Heimpforte. Die Freinsheimer Stadttore und ihre ursprünglichen Namen.” Heimat-Jahrbuch 2010 des Landkreises Bad Dürkheim. Haßloch 2009. S. 201-203.

“Leyfart von Heppenheim – ein unbekanntes Geschlecht des pfälzischen Niederadels.” Mitteilungen des Historischen Vereins der Pfalz 107 (2009), 111-121.

“Die „avita nobilitas“ des Johann Bernhard von Ehm – doch wörtlich zu nehmen ?” Mitteilungen des Historischen Vereins der Pfalz 107 (2009), 457-458.

Hans-Helmut Görtz und Reinhard Düchting, “Poesie in Freud und Leid: Das Leben des lutherischen Kallstadter Pfarrers Elias Saur (1642-1694),” Blätter für pfälzische Kirchengeschichte 77 (2010), 169-181.

Hans-Helmut Görtz und Mark Spoelstra, 300 Jahre Retzerhaus in Freinsheim – aber nicht dasjenige, das man kennt. Pfälzisch-Rheinische Familienkunde 17 (2010), S. 72-77.

“Das Haus verkauft, die Brücken abgebrochen – Freinsheimer Auswanderer nach Amerika im frühen 18. Jahrhundert”

Pfälzisch-Rheinische Familienkunde 17 (2010), S. 118-128.

“Betreutes Wohnen Anno dazumal – Verpfründung in das Spital Dürkheim um das Jahr 1600.” Heimat-Jahrbuch 2011 des Landkreises Bad Dürkheim, Haßloch 2010, S. 96-99.

“Literatur war sein Leben – Freinsheim verdankt Gert Weber Bücherei und Sinsheimer-Preis.” Heimat-Jahrbuch 2011 des Landkreises Bad Dürkheim, Haßloch 2010, S. 134-137.

“Von Freinsheim nach Melk: Der Benediktinermönch Johannes Wischler (1383 – 1455).” Heimat-Jahrbuch 2011 des Landkreises Bad Dürkheim, Haßloch 2010, S. 230-233.

“Graf Emich VIII. hilft Ostertag-Stiftung – Urkunden-Fund im Zentralarchiv der Evangelischen Kirche der Pfalz.” Heimat-Jahrbuch 2011 des Landkreises Bad Dürkheim, Haßloch 2010, S. 193-194.

Hans-Helmut Görtz und Andreas Hecht, “Freinsheim und die Herren vom Stein,” Mitteilungen des Historischen Vereins der Pfaz 108 (2010), S. 121-151.

“Johannes (Giovanni) Praga – ein Migrant des 18. Jahrhunderts – der erste Italiener in Freinsheim war Kaufmann und gut integriert”

Heimat-Jahrbuch 2012 des Landkreises Bad Dürkheim, Haßloch 2011, S. 49-51.

“Unterwegs zu den Wurzeln – Sinsheimers Großneffe Fred Kolm besuchte Freinsheim”

Heimat-Jahrbuch 2012 des Landkreises Bad Dürkheim, Haßloch 2011, S. 190-192.

Dr. Görtz also presents a number of lectures with slides.

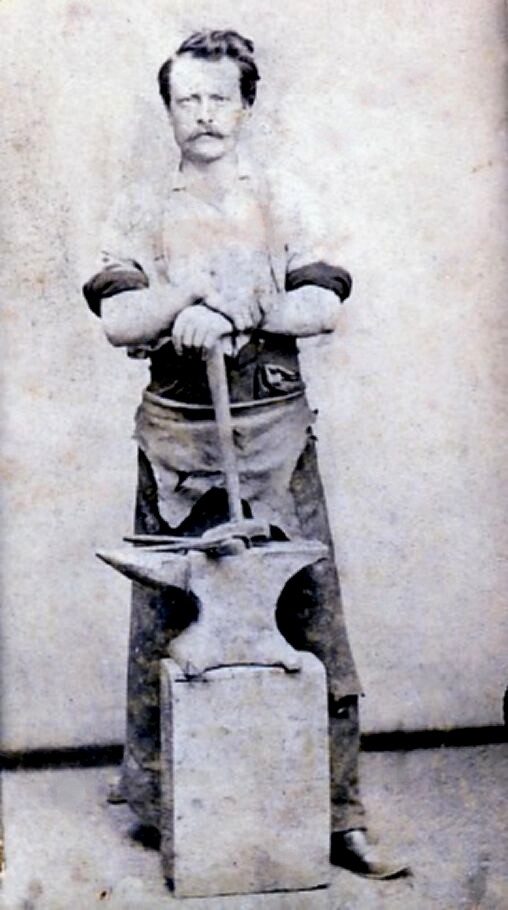

What is the working title of your book?

What is the working title of your book?