When I started writing my thesis, I had no idea how many “heavyweights” lived in the early nineteenth century.

When I first looked for thinkers, writers, artists, and musicians of the times, Goethe and Schiller emerged from the get-go. But the big names just kept piling up.

The Cleveland German Cultural Garden honors only a few of these 19th century German VIPs: Father Jahn, Humboldt (Alexander, and there was also his brother, Prussian education system brainiac Wilhelm), Goethe, Schiller, Heine, Lessing, Beethoven, Bach … “Oh wow!” I thought, standing there among the statues.

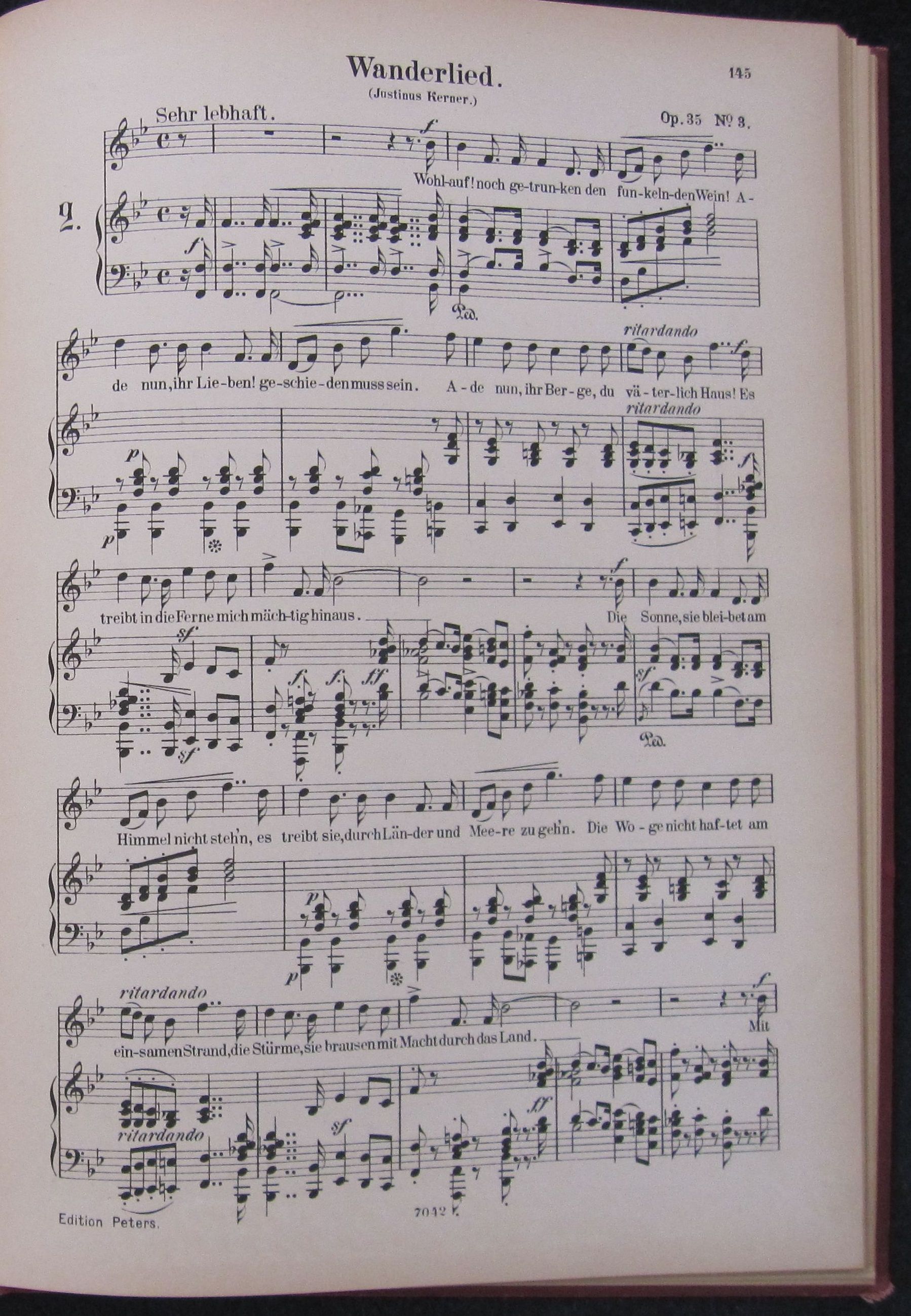

Before long, I had also added Mendelssohn, Schubert, Kant, Hegel, Marx, Engels, and Nietzsche to the list. (“How do you keep it from becoming … ponderous?” a friend asked. Ha! My concern is whether great-great-grandfather, rural farm boy turned Cleveland blacksmith, even knew these scholars and artists shared space with him on the planet.)

I can’t help but explore this stuff, like a pilot flying over the Nazca Lines and trying to make out vague shapes in the desert tundra.

What a treat it was to come across Peter Watson’s book The German Genius. Published in 2010, the early chapters are a compendium of the kind of thing that keeps drawing me to the nineteenth century mindset. The stuff about Pietism in particular was a real forehead smacker.

The idea of doubt, that humans are self-directed, not God directed, emerged as a movement in the late 18th century. The “Third Renaissance, between Doubt and Darwin,” Watson claims, occurred around the years 1697 (Essay Concerning Human Understanding – Locke) and 1859 (Origin of Species – Darwin), when all of the above Germans, and many more, greatly influenced the progress of civilization.

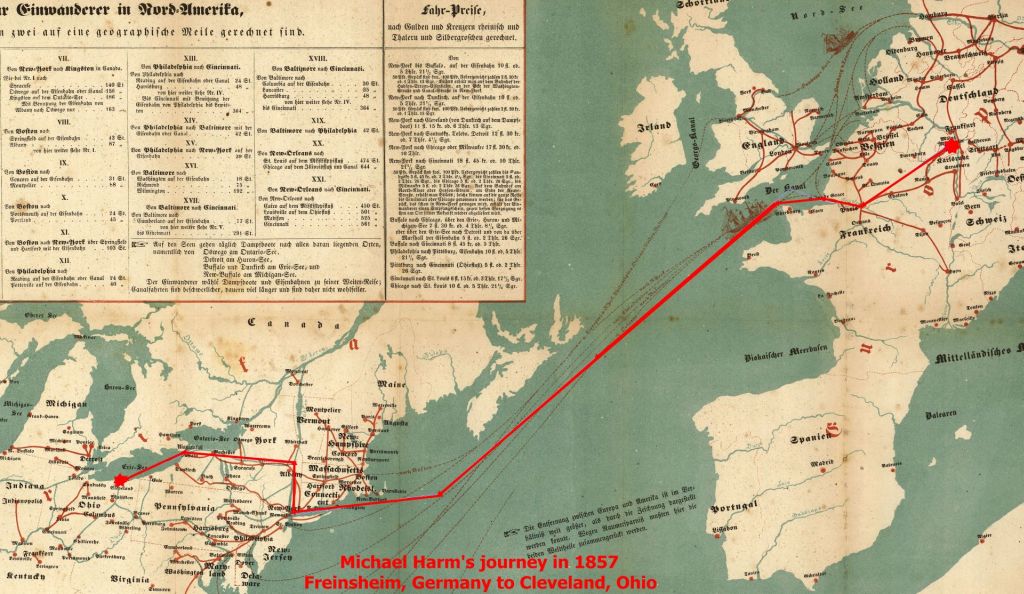

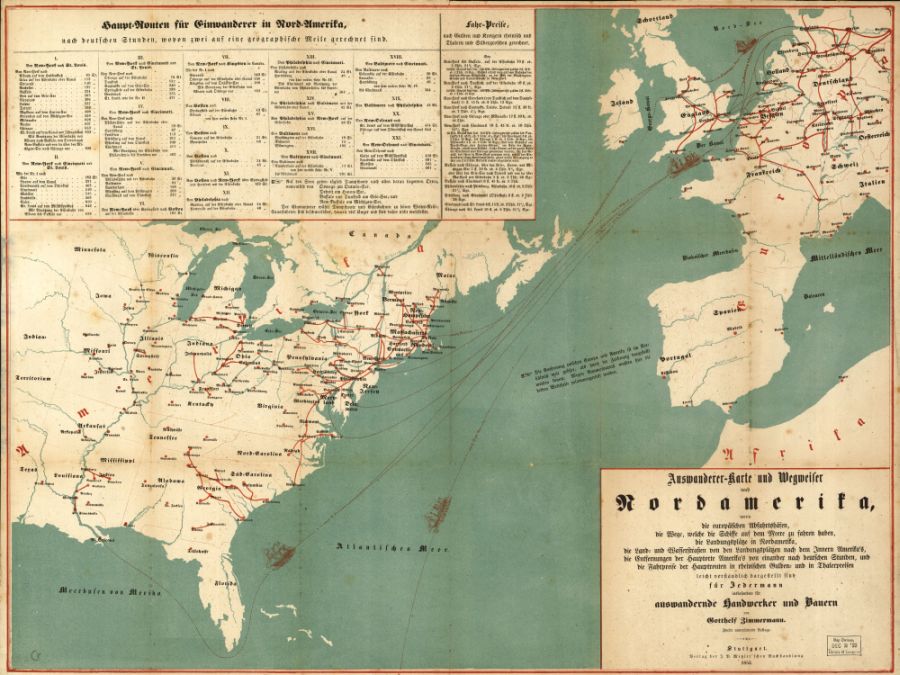

“Oh wow!” I’m thinking (again). Watson examines scientific and social discoveries, advances in education and exploration, the Prussian-dominated world and “separatist” position of Germany in Europe in those years, yet it feels to me like he left something out. Nowhere (so far) have I come across mention of the great “Auswanderung,” the emigration of millions upon millions of Germans from the fatherland in the nineteenth century. A disconnect that has me wondering …