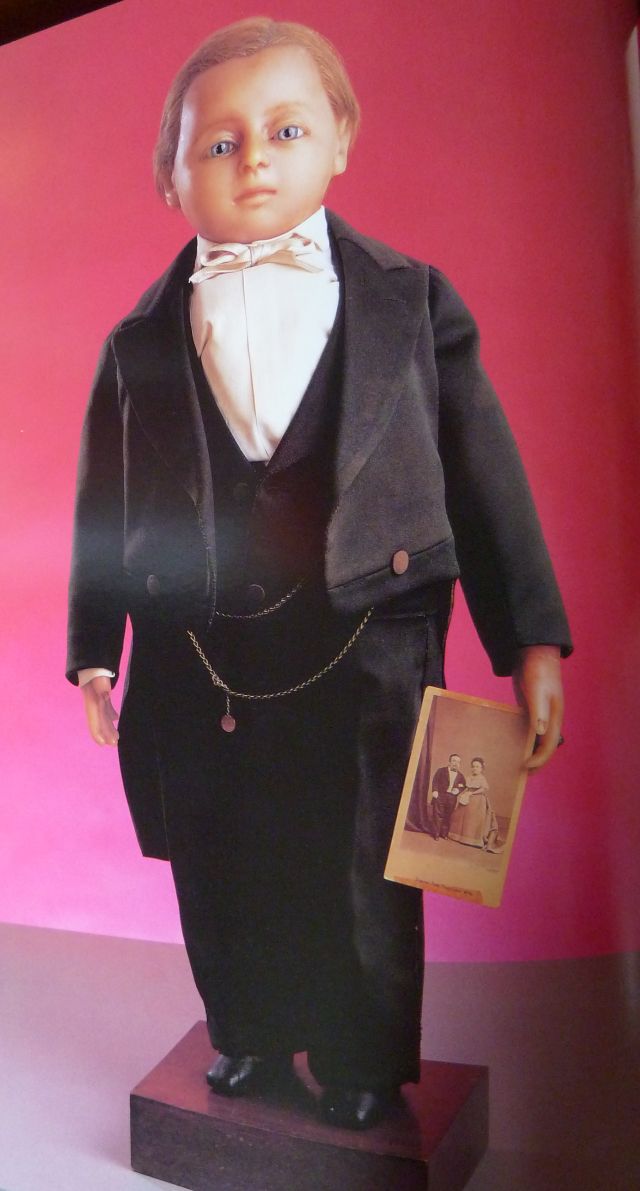

On my recent visit to the (now-closed) Rosalie Whyel Museum of Doll Art, a doll replica of Tom Thumb was on display.

Oh right, you’re thinking, Tom Thumb, of the English fairy tale. The little guy who, among other mishaps, gets cooked in pudding and swallowed by a giant, right? Wrong.

While fairy tales endure, living breathing persons often pass out of the public awareness. One legendary personage of the mid-19th century was General Tom Thumb. Born in 1838, Charles Sherwood Stratton’s growth slowed considerably after the first six months of his life. P.T. Barnum, Stratton’s distant relative, took him under his wing and made a sensation of him in Europe. Stratton adopted the stage name of General Tom Thumb, and became a very wealthy young man. He first appears in the Cleveland newspapers in 1857.

“The Lord Mayor of London has prohibited Tom Thumb’s carriage from parading the city.” –2/25/1857, The Cleveland Daily Herald

“The Lord Mayor of London has prohibited Tom Thumb’s carriage from parading the city.” –2/25/1857, The Cleveland Daily Herald

“We understand that Gen. Tom Thumb is dangerously ill, and not expected to recover. He is, we believe, in France.” — 12/11/1857

“General Tom Thumb held a levee [reception] at the Museum, in New York, on Friday last. … He is now but little larger than a three years old child. He wears a cap surmounted by a crown not unlike those worn by the officers of the British steamers. He is quite communicative–is twenty-one years old–lives in fine style in Bridgeport, and keeps his fast team like any gentleman of the town or ton, though he seldom drives out without company.” — The Scioto Gazette, Chillicothe, OH, 3/20/1860

“Gen. Tom Thumb INJURED. –This notable personage met with a severe accident in St. Catharines, Canada, last Monday. A letter published in the Toronto Leader says:

An accident, which might have been attended with very serious, if not fatal effects, occurred this morning to no less a personage than Gen. Tom Thumb. He and his suite left the Welland House in high spirits, in a conveyance drawn by two spirited horses; they had just turned into the principal street, when the axle broke, which started the horses. The near fore wheel came off, precipitating the whole of the party into the mud, which, in consequence of the late heavy rains, was very deep. The General alighted on his back, striking his head and taking the hair clean off his crown; he was bruised also severely on his thigh. The little General, however, bore the mishap like a true hero, his favorite pipe remained in his mouth, and he continued to smoke while lying on his back in the mud.–11/14/1861 – The Daily Cleveland Herald

An article in the end of 1861 reports that while Tom Thumb toured Chicago, robbers attempted to steal his jewels, but were thwarted. Then, in May of 1862, General Tom Thumb arrives in Cleveland at 24 years of age, reportedly 32 inches high and weighing 38 pounds.

“Gen. Tom Thumb. The levees of the above ‘beau ideal’ of man continue to be well attended by delighted audiences. His impersonation of the ‘Grecian Statues’ is decidedly artistic, and call forth repeated plaudits from his audience. Mr. DaVere’s popular and pleasing ballads, and Mr. Tomlin in ‘Simon the Cellarer’ and the ‘Little Fat Man,’ tend to keep the audience highly pleased during the intervals occasioned by change of dress. To-morrow he takes his final farewell of our citizens, for he intends visiting very shortly the golden shores of California and Australia.”

In 1863, Gen. Tom Thumb married Lavinia Warren. (Notice that, in the picture above, the doll is holding a photograph of Tom Thumb and his wife.) The following article appeared shortly after their wedding:

An Intrusion upon Tom Thumb and Wife.–Mr. and Mrs. Stratton, who are now traveling through this country to let people see how small they are, stopped at the Jones House, in Harrisburgh, on their recent visit. Their levees were densely thronged, and hundreds failed to gain admittance. Among those who were disappointed were several staid gentlemen belonging to the hotel, who prevailed upon the agent to conduct them to Tom’s room, after the evening levee was over. Followed by a crowd of spectacled and reputable gentlemen, the agent proceeded to the chamber, knocked at the door, and was summoned to ‘come in.’ But when the door opened, there stood Tom in his unmentionables, while Mrs. Thumb was invisible. She had just retired, taking refuge among the cambric ruffles of a linen pillow slip, after repeating her tiny prayer, doubtless, of ‘Now I lay me down to sleep all wrapped up in a little heap.’ But the General stood defiant, with boots in hand, his brow gathered into a frown at the intrusion, which no explanation of the agent could dispel. Nothing was left but retreat.” — The Daily Cleveland Herald, 5/11/1863

The couple went on to give birth to a baby girl, and by 1864 were touring London, Paris, and Rome. Charles Sherwood Stratton lived to the age of 45.