Early on in the research trail of my immigrant ancestors, I talked with writing friend Christine about my quest for passenger lists. She suggested the Seattle Public Library (SPL).

“Have you been to the 9th floor? There’s a great section on genealogy. You should definitely go.”

I knew she was right, but as time passed, whenever I thought about going something else always got in the way. Until the other day when I was riding the bus along 4th Avenue with 45 minutes to spare, and that smushed 4-layer cake of a library building loomed into view. On impulse I pulled the bus stop cord and hopped out to have a look.

I knew she was right, but as time passed, whenever I thought about going something else always got in the way. Until the other day when I was riding the bus along 4th Avenue with 45 minutes to spare, and that smushed 4-layer cake of a library building loomed into view. On impulse I pulled the bus stop cord and hopped out to have a look.

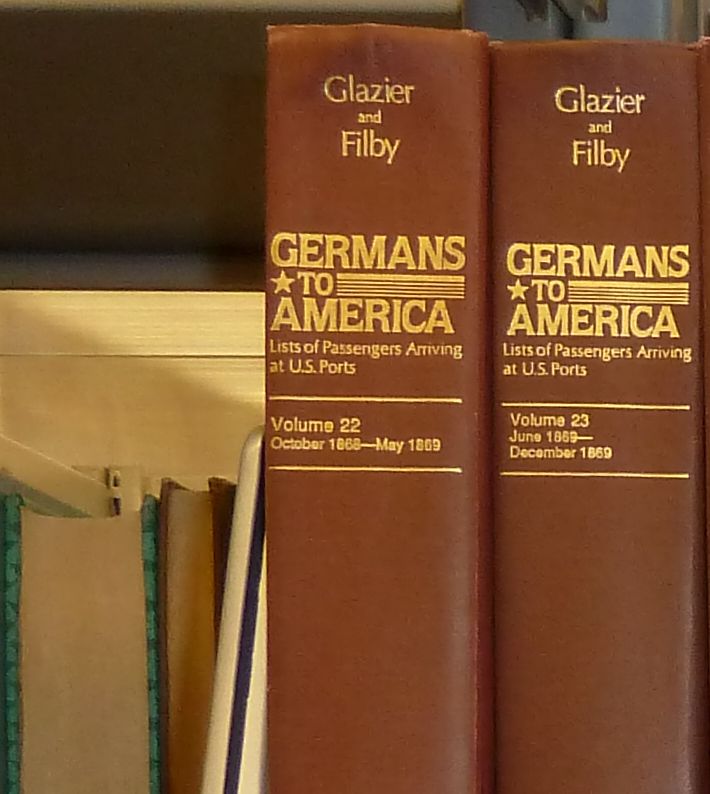

When I finally arrived on the 9th floor (it was a long and winding up-ramp), the first thing I happened upon was a shelf of “Germans to America” bound volumes. I had no idea that “Lists of Passengers Arriving at U.S. Ports,” exclusively Germans, had been compiled in chronological order. I had found my ancestor Michael Harm the hard way, by scrolling through hours and hours of microfilm at NARA.

When I finally arrived on the 9th floor (it was a long and winding up-ramp), the first thing I happened upon was a shelf of “Germans to America” bound volumes. I had no idea that “Lists of Passengers Arriving at U.S. Ports,” exclusively Germans, had been compiled in chronological order. I had found my ancestor Michael Harm the hard way, by scrolling through hours and hours of microfilm at NARA.

I pulled out the “Germans to America” volume for the proper time period thinking, this looks so easy. Why didn’t I come here sooner?

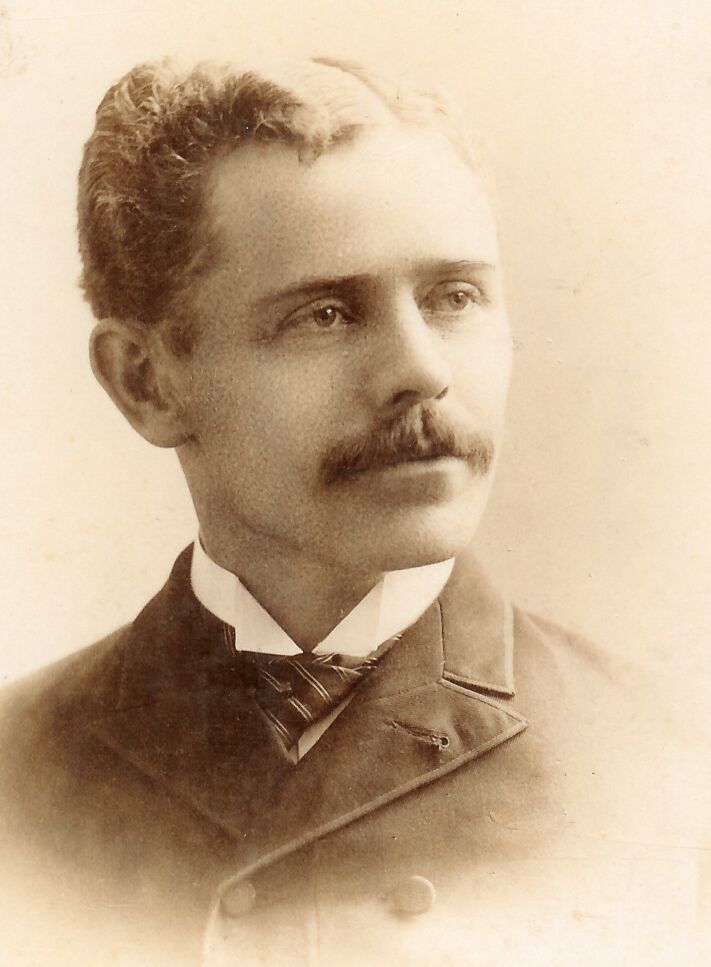

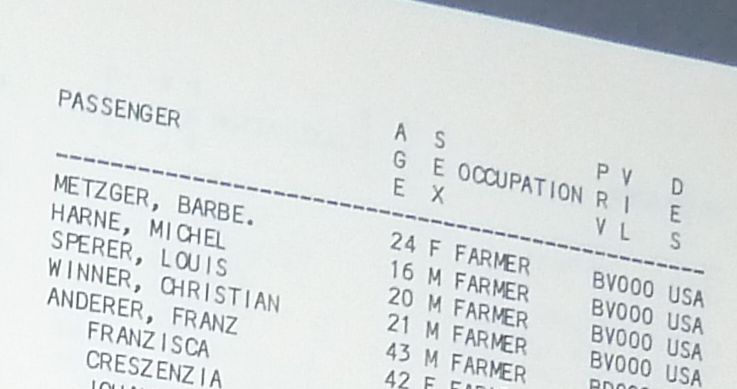

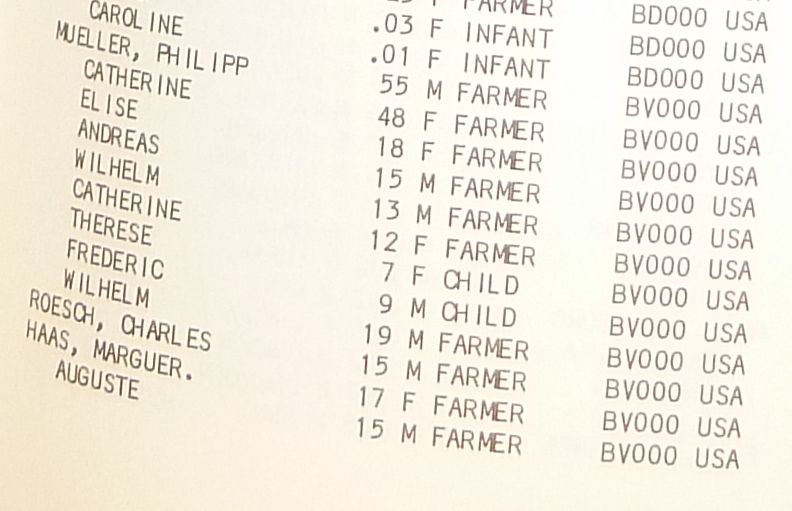

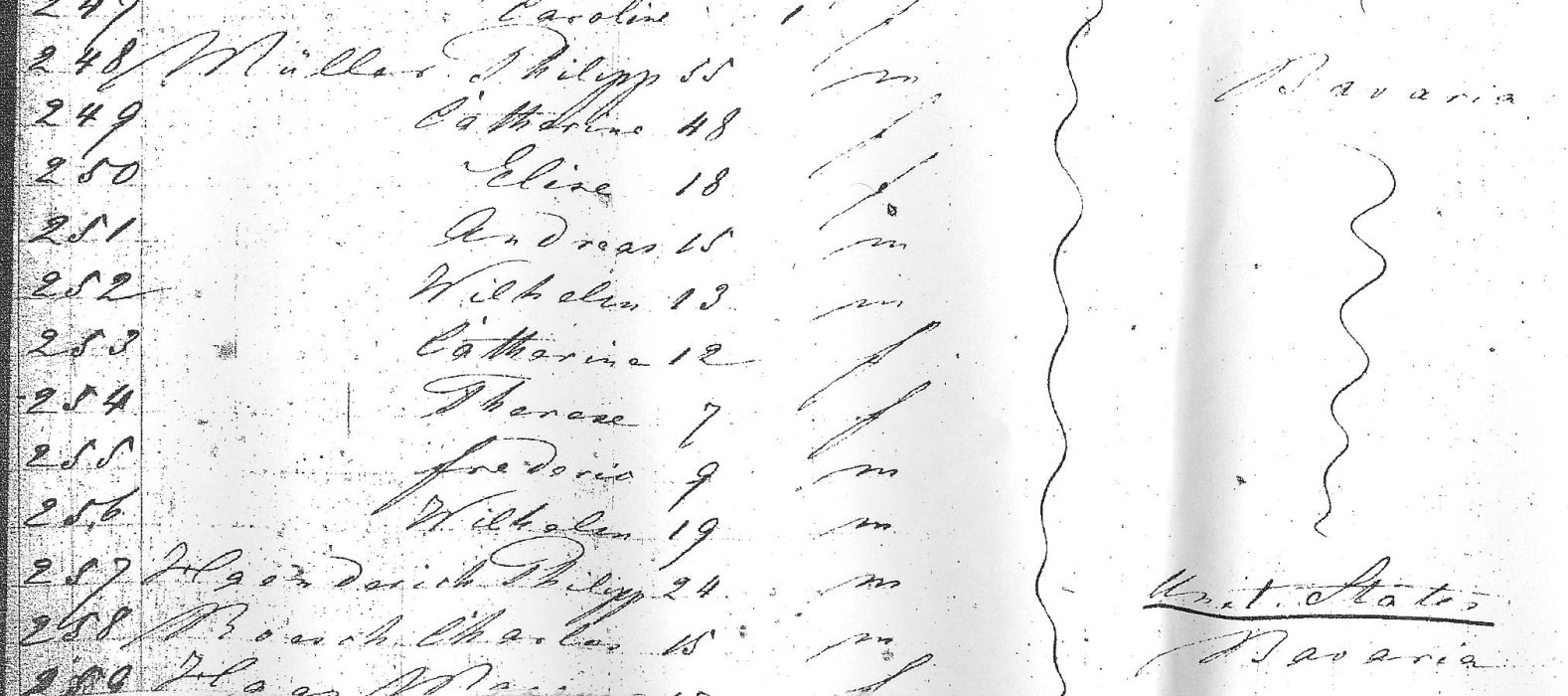

Sure enough, there he was, June 30, 1857 on the good ship Helvetia. You see him there? Michael Harm? Okay, Michel Harne. Still, I’m convinced that’s him, because from letters in my possession I know he made a 43 day journey in 1857 when he was 16, leaving behind his immediate family, voyaging from Le Havre, France to New York City. One other corroborating piece of data on the list clinched the deal. Nearby Michel Harne on the list was the name Philipp Haenderich of the USA. Haenderich (Handrich) was the same last name as Michael’s grandparents on his mother’s side. It makes sense that Michael’s parents would not send him unaccompanied, not if they could help it.

Sure enough, there he was, June 30, 1857 on the good ship Helvetia. You see him there? Michael Harm? Okay, Michel Harne. Still, I’m convinced that’s him, because from letters in my possession I know he made a 43 day journey in 1857 when he was 16, leaving behind his immediate family, voyaging from Le Havre, France to New York City. One other corroborating piece of data on the list clinched the deal. Nearby Michel Harne on the list was the name Philipp Haenderich of the USA. Haenderich (Handrich) was the same last name as Michael’s grandparents on his mother’s side. It makes sense that Michael’s parents would not send him unaccompanied, not if they could help it.

But when I looked in the “Germans to America” volume for the name Philipp Haenderich, to my surprise, no Haenderich was listed.

But when I looked in the “Germans to America” volume for the name Philipp Haenderich, to my surprise, no Haenderich was listed.  If I had relied on this bound volume alone, I might have missed some vital data.

If I had relied on this bound volume alone, I might have missed some vital data.

A cautionary tale. These volumes are called “Germans to America,” and on the handwritten list, Philipp Haenderich is listed as a U.S. citizen so his name was not included.

The presence of Philipp Haenderich also brings up another point. When checking passenger lists and census data, it is almost as important to look at the names nearby as at the names of whoever we’ve been searching for. People tend to wait in line with people they know. Census information also provides more data than we might realize, because relatives often live on the same street, so you might find someone else nearby. At the very least, if you look at those listed around your ancestor, you’ll get a glimpse of the people in their lives.