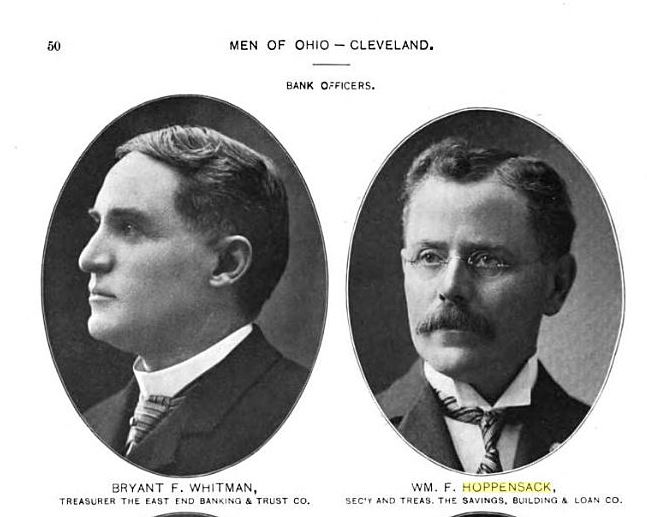

My family has saved a book called Men of Ohio in Nineteen Hundred because our great grandfather William F. Hoppensack is pictured there.

Quite a few historic Ohio men are listed there. It can be found on Google Books here. William F. Hoppensack ran for office as bank commissioner several times, but never succeeded. His political career was not as esteemed as a few other Ohio greats.

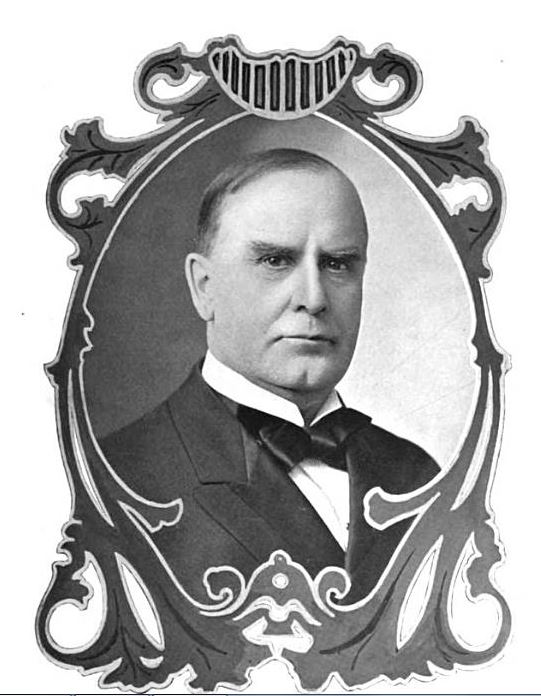

William McKinley appears on page 1 of Men of Ohio, as he was then serving his term as President of the United States (1897-1905). Wait, 1905? Right, that’s how long his term would have lasted — if he had lived. Sadly, he was assassinated at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, NY in 1901. Links to articles about that tragic time are found here. McKinley was not the first Ohio man to lose his life as president.

William McKinley appears on page 1 of Men of Ohio, as he was then serving his term as President of the United States (1897-1905). Wait, 1905? Right, that’s how long his term would have lasted — if he had lived. Sadly, he was assassinated at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, NY in 1901. Links to articles about that tragic time are found here. McKinley was not the first Ohio man to lose his life as president.

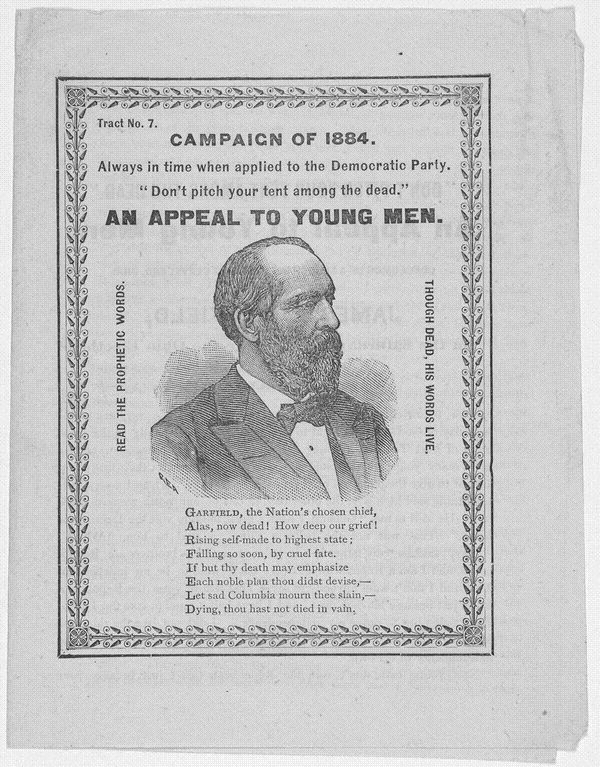

James A. Garfield was another. Garfield was born in Moreland Hills, Ohio, where a replica log cabin now stands in tribute to the place of his birth. Garfield worked on the side of the new Republican Party and Abraham Lincoln in the 1850s. After all, he too was a rags-to-riches kind of guy. His bid for the White House was an attempt to rid a by-then entrenched system of patronage, which had taken hold during the administrations of Johnson, Grant and Hayes. Here’s one of his more intriguing quotes:

Whoever controls the volume of money in our country is absolute master of all industry and commerce…when you realize that the entire system is very easily controlled, one way or another, by a few powerful men at the top, you will not have to be told how periods of inflation and depression originate.

Read about some of his other visionary ideas at Wikipedia. Garfield was president for 200 days — he took office in March of 1881, was shot in July by an attorney who did not get an expected governmental post, and died of the bullet wound in September of that same year. The following is an epitaph I came across recently: