Recently, my brother was going through boxes kept after Dad passed away and unearthed two tools.

“They say Harm on them,” he said to me over the phone, “so I thought you might want them.”

Yes! Of course I want them. I wrote a novel based on the true story of my great-great grandfather Michael Harm and his Harm & Schuster Carriage Works, and by now I’ve collected a small museum of items: photos, a goat cart, a beer stein. I’d not come across any tools, though.

“One of them looks like a carpenter’s plane,” my brother added. “Not sure why it was kept, though.”

“I bet I know why!” Through genealogy research, I’d discovered the carriage works was a family affair. Michael Harm married Elizabeth Crolly. Her father worked as a carpenter at Harm & Schuster. “Your 3x great grandfather, Adam Crolly, was a carpenter. He’s pictured in the old photos.”

Above in this photo, circa 1874, of the Harm & Schuster Carriage Works, our 3x great grandfather Adam Crolly is shown in the upper right window. In the photo at right, Adam Crolly is holding an adze — another tool of his carpentry trade.

Above in this photo, circa 1874, of the Harm & Schuster Carriage Works, our 3x great grandfather Adam Crolly is shown in the upper right window. In the photo at right, Adam Crolly is holding an adze — another tool of his carpentry trade.

“Then there’s a knife of some kind, I’m not sure what it’s for,” my brother said. “It has a curved blade, something like an ulu.”

That tool remained a mystery until a couple of weeks later when my brother and I met up for a family gathering. After much speculation about the knife and its uses, my niece and I did some internet browsing and found a poster of antique tools, one of which resembled ours. “Couteau à pied” the inscription underneath it read. Literal French meaning: “knife in foot.” Or possibly, “knife for foot.” Still not quite right. More digging turned up a probable English counterpart: a couteau à pied is a type of trimming tool, a round head knife for cutting leather.

Okay, but what does leather trimming have to do with carriage-making, you may ask? Answer: trimming is another term for upholstering. A carriage-making company in the 19th century generally consisted of four departments: blacksmithing, carpentry, painting, and trimming, in other words, upholstering of carriage seats, cushions, dashes and what not. This trimming knife has the inscription Harm on it. The rough-hewn nature of it leads me to believe it was forged by hand by my great-great grandfather, Michael Harm.

Why hang onto these seemingly crude old tools? I’m keeping them not only for sentimental value. I see them as treasures of the artisan craft livelihoods of our German immigrant ancestors, of their toil and talent, of the legacy they left for posterity.

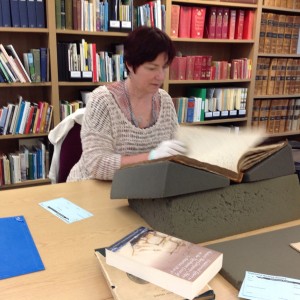

Tinsmiths of the day were also known as tinkers, handy at most repairs. Upon further research, I turned up this book: Last of the Tinsmiths: The Life of Willie MacPhee by Sheila Douglas. In a nutshell:

Tinsmiths of the day were also known as tinkers, handy at most repairs. Upon further research, I turned up this book: Last of the Tinsmiths: The Life of Willie MacPhee by Sheila Douglas. In a nutshell: I had the good fortune this past month to be in London. On a visit to Westminster Abbey, this bell caught my eye, hanging near the

I had the good fortune this past month to be in London. On a visit to Westminster Abbey, this bell caught my eye, hanging near the  “It’s a cross made from the wedding rings of her first marriage,” Dad said. “He died in WWI.”

“It’s a cross made from the wedding rings of her first marriage,” Dad said. “He died in WWI.”

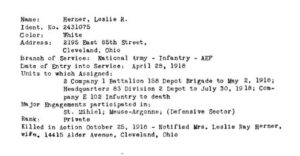

Leslie was 29 years old at the time of his death. May turned 29 a month later. Thirteen years later, she married again but remain childless. She outlived her first husband by 58 years. Leslie Ray Herner is not an “unknown warrior.” His cross stands in the graveyard of the

Leslie was 29 years old at the time of his death. May turned 29 a month later. Thirteen years later, she married again but remain childless. She outlived her first husband by 58 years. Leslie Ray Herner is not an “unknown warrior.” His cross stands in the graveyard of the