Jet-lagged, but arrival back in Freinsheim has brought a barrage of sights to share.

Matthias and I have reviewed the calendar during my stay. The story of the Harm brothers descendants continues.

Jet-lagged, but arrival back in Freinsheim has brought a barrage of sights to share.

Matthias and I have reviewed the calendar during my stay. The story of the Harm brothers descendants continues.

The last time I visited Freinsheim was the fall of 2010 during the annual “Wine Hike” / Weinwanderung. (Ostensibly, I was there to research my novel, but hey, a girl can have fun too, right?)

The last time I visited Freinsheim was the fall of 2010 during the annual “Wine Hike” / Weinwanderung. (Ostensibly, I was there to research my novel, but hey, a girl can have fun too, right?)

Soon I’ll be headed back there, about the same time of year, but so much in my life has changed. I’ve studied more German, for one thing. I feel as if I’m so much closer to my relatives, for another. But most of all, I’ve now made the leap from aspiring writer to published author. The book I went there to research — relying on Freinsheimer hospitality for a whole month! — has become a reality.

And they’re setting up a book talk for me, while I’m there, in a renovated old hospital that is now used as a cultural venue. My presentation will be Monday, October 6 at 7:00 p.m. I’ll talk about my book (hopefully in German) and read from it, and will have help from my relatives during the Q&A. Heartfelt thanks to the Weber family for setting this up. A link to the announcement of the event (in German) is here.

When I visited the Pfalz region of Germany, I especially enjoyed the wines. The Rieslings are crisp, not cloying, the Spätburgunder is as fine as a good Pinot Noir, and the sparkling Sekt is equal in quality to French champagne.

Wine-making is so ubiquitous to the culture and lifestyle of the Pfalz, the entire cellar of the Bad Dürkheim Heimatsmuseum is dedicated to a viticulture exhibit. The rack shown here is an example of the traditional method of fermenting champagne. According to the Heimatsmuseum curator, it was an iffy proposition — 10- to 20-percent of the bottles could be counted on to explode, the champagne wasted.

Wine-making is so ubiquitous to the culture and lifestyle of the Pfalz, the entire cellar of the Bad Dürkheim Heimatsmuseum is dedicated to a viticulture exhibit. The rack shown here is an example of the traditional method of fermenting champagne. According to the Heimatsmuseum curator, it was an iffy proposition — 10- to 20-percent of the bottles could be counted on to explode, the champagne wasted.

Wines from the Bad Dürkheim region were exported to Cleveland in the 19th century, thanks to the Dürkheimer wine-makers George and John Fitz and a Cleveland wine importer named Leick of Kirchheimbolanden. (Apparently Leick and his brother married the Hege sisters from Dürkheim, so a connection was made.)

In particular, the Fitz brothers produced the 1848 Dürkheimer Firemountain label especially for export. Records show the wine was also exported to New York City, Cleveland and New York City being areas with high Palatine immigrant populations. While the year on a label normally indicates the vintage, in this case, all wines carried this year. The year 1848 was a reference to the 1848 Revolution for democracy, the Fitz brothers reaching out in solidarity to exiles forced to immigrate to America after the revolution was crushed. It’s not clear how long the 1848 label lasted. But wine exports continued until Prohibition brought an end to the once lucrative trade.

These days, the Mosel region seems to dominate German wine imports to the U.S. However, I recently stumbled on a delightful surprise. The Fitz wine-makers of Bad Dürkheim are still in business. Now called the Fitz-Ritter Winery, the history of their revolutionary 19th century activities is even posted proudly on their website:

SEKT – SPARKLING WINE WITH DEMOCRATIC ROOTS

In 1837, the Fitz estate founded the first “Champagne“ Production in the Palatinate (second in all of Germany). Johannes Fitz, known as “the Red Fitz,” had imported the necessary know-how from the Champagne region of France which had been his exile home following his activity for the German Democracy movement at the Hambach Festival in 1832.

Five years later the first „Palatine Champagne“ emerged from the Bad Dürkheim winery. …Just as it was back then, today the Sektkellerei Fitz (Sekt is the German word for sparkling wine) still produces “Sekt” from Burgundy and Riesling wines by traditional bottle fermentation.

No wonder the Fitz wine-makers reached out to those suffering exile in 1848–John Fitz had been an exile himself in 1832. I checked into it, and the Fitz-Ritter wines are again being exported to the U.S. Oh happy day!

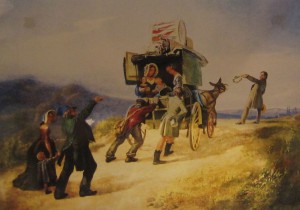

Browsing through photos of my visit to Germany a few years ago, I came across this image of a traveling music band, a photo I took of a display at the Culture House Museum in Bad Dürkheim.

Browsing through photos of my visit to Germany a few years ago, I came across this image of a traveling music band, a photo I took of a display at the Culture House Museum in Bad Dürkheim.

The scene reminded me of a wonderful museum I visited during my travels: the Pfälzer Musikantenland-Museum in Kusel at the Burg Lichtenberg. It’s a stunning setting, a former castle that’s now something of a village, with shops, a dining hall and a family and youth hostel guest house.

The scene reminded me of a wonderful museum I visited during my travels: the Pfälzer Musikantenland-Museum in Kusel at the Burg Lichtenberg. It’s a stunning setting, a former castle that’s now something of a village, with shops, a dining hall and a family and youth hostel guest house.

At the Musikantenland Museum, I picked up a flyer that provided “A Little Bit of History.”

The western Palatinate (primarily the area comprised by the former Bavarian Rhine Landkommissariate of Kusel, Hornburg, Kaiserslautern and Kirchheim), known as “Musician Country” is one of the few regions of the German-speaking cultural world with a tradition of itinerant musicians or Wandermusikanten.

After the Palatinate attained freedom from French occupation in the era of Napoleon (1797-1814), one encounters the vocational description of musician more and more often in western Palatinate archives. The freedom from guild obligations allowed a considerable number of local popular musicians to make a living from their natural talents. Economic causes (overpopulation, famine, bad harvests in the poor soil of the western Palatinate, similar to the reasons which drove many people from the Palatinate to emigrate to America in the 19th century) were also responsible for the first travels of musicians around 1830. They traveled first to neighboring countries (France, Switzerland) or to other German states (Prussia), then to the rest of Europe (Spain, Holland, the British Isles, Scandinavia, Russia etc.) and finally — after the middle of the century — literally to the entire civilized world.

After thorough practice during the winter, these western Palatinate musicians set out in the spring and remained away until fall, if they were seeking to make their living in Europe, or came home after two, three, or more years if they traveled overseas.

In the prime years around the turn of the century, approximagely 2,500 musicians were traveling about, earning the considerable sum of many millions of gold-marks annually.

The Musikantenland Museum at Burg Lichtenberg houses not only instruments, uniforms, and so on, but also souvenirs the men carried back from their travels. More information about the itinerant bands (and their demise) can be found at a brief history of Itinerant Musicians.

Posted in 19th century history, Freinsheim and Palatinate history, The Last of the Blacksmiths: A Novel, Travels in Germany

Tagged 19th century itinerant musicians, Lichtenberg Castle, Lichtenberg hostel guest house, Musikantenland Museum, Palatinate music museum, Palatinate musicians, wandering musicians

The Tenement Museum visitor center and shop at 103 Orchard Street, New York, New York has a great selection of books. I got caught up in such titles as:

When Did the Statue of Liberty Turn Green?: And 101 Other Questions About New York City, until a title caught my eye a few shelves over: The German-American Experience, by Don Heinrich Tolzmann. A must-buy. When I brought it to the counter, the salesperson sighed.

“You found one of two books we carry here about German Americans. I wish we had more.”

I should have asked her what the other title was, but my tour of 97 Orchard Street was about to begin. Back home, when I visited the Tenement shop on-line, I saw what the sales clerk meant. In addition to books about New York, the shop inventory listed books “Of Irish Interest,” “Of Jewish Interest,” and “Of Italian Interest.” Nothing “Of German Interest.” Humph. Maybe I bought the last one.

Tolzmann’s The German-American Experience is well researched. I love how it includes a write-up of Charles Sealsfield (a pen name–his real name was Karl Postl), whose books were as influential as James Fenimore Cooper’s “Leather-stocking Tales” series in giving 19th-century Germans an idealized vision of America.

Tolzmann also briefly mentions “The Hambacher Fest and the Thirtyers,” something I rarely come across in English versions of German history. The 1832 Hambacher Fest is where the black, red and gold tricolor was first flown as a symbol of democratic rebellion.

Tolzmann also briefly mentions “The Hambacher Fest and the Thirtyers,” something I rarely come across in English versions of German history. The 1832 Hambacher Fest is where the black, red and gold tricolor was first flown as a symbol of democratic rebellion.

From May 27-30, 1832, tens of thousands of craftsmen, students, farmers, officials, and young intellectuals gathered at the ruins of the castle of Hambach to listen to speeches on liberty, reform, and the tyranny of the German princes. Like the Wartburg Fest of 1817, the Hambacher Fest culminated in arrests, dismissals of professors from their positions, espionage, censorship, and police surveillance. These oppressive measures caused many to emigrate to America. (The German-American Experience, p. 166)

Hambach Castle, situated in the foothills of the Haardt Mountains near Neustadt, is now a museum. I found the interpretive displays there very informative. Here are just a few personalities of the day:

Friedrich Deidesheimer

The merchant and vineyard owner Friedrich Deidesheimer, of Neustadt an der Haardt, was a member of the Civil Guard, and in 1832 was a signatory to the invitation to the Hambach Festival. On May 27, Deidesheimer delivered a speech calling for a guarantee of civil rights and liberties by the prince and concluded with an appeal: “Long live freedom / Long live the order.”

Daniel Friedrich Ludwig Pistor

Daniel Friedrich Ludwig Pistor, of Bergzabern, studied law in Munich, receiving his doctorate in 1831. The political climate in Bavaria had intensified under King Ludwig I. At the Hambach Festival, Pistor gave a speech so revolutionary that he had to flee to France to avoid arrest. In absentia, he was sentenced to one year in prison. His radical writings in Paris earned him another indictment and conviction for treason. Living as an exile, Pistor joined the “covenant of the outlaws,” a circle of emigres. A clemency request was rejected by King Ludwig I.

Following the 1832 Hambacher Fest, which drew protesters from all over Europe, a June rebellion in Paris also failed. You may have heard something more about that French uprising than you realize. Does Les Miserables sound familiar?

Check out this new promotional Youtube spot about Freinsheim in the Rhineland-Palatinate. Visiting there is such a fun-loving, picturesque experience. You can even hear the tolling of the church bells in one part. (Sure, it’s narrated in German, but you’ll get the idea.) I clipped one of my favorite shots, this picture of a kid leaping to touch the top of the tunnel along the inner ring of the towns ancient fortified wall.

Posted in General, The Last of the Blacksmiths: A Novel, Travels in Germany

Tagged Freinsheim

Do I have it backwards? Isn’t it supposed to be “add water to the wine?” Today, perhaps. But in Roman times, and still in the Palatinate, a favorite quaff is the Wein-schorle, a healthy dose of sparkling mineral water with wine added.

Do I have it backwards? Isn’t it supposed to be “add water to the wine?” Today, perhaps. But in Roman times, and still in the Palatinate, a favorite quaff is the Wein-schorle, a healthy dose of sparkling mineral water with wine added.

On my travels in the Palatinate (Pfalz) in 2010, cultural disorientation smacked me on the forehead my first night, while visiting the Bad Dürkheim Wurstmarkt. In one of the many vendor tents of this wine festival (which dates back some 600 years), I had no idea what any of the offerings on the sign meant. What on earth was a Wein-schorle? (a spritzer) A Trollschoppen? (a bumpy 0.5 litre pint glass, unique to the Palatinate). Traubensaft? (juice) Sprudel? (mineral water)

On my travels in the Palatinate (Pfalz) in 2010, cultural disorientation smacked me on the forehead my first night, while visiting the Bad Dürkheim Wurstmarkt. In one of the many vendor tents of this wine festival (which dates back some 600 years), I had no idea what any of the offerings on the sign meant. What on earth was a Wein-schorle? (a spritzer) A Trollschoppen? (a bumpy 0.5 litre pint glass, unique to the Palatinate). Traubensaft? (juice) Sprudel? (mineral water)

What’s more, I couldn’t help wondering, why are they diluting their wine? It seemed so strange, but turned out to be a wise choice — the Wein-schorle kept me hydrated, and alert enough late into the evening to be able to enjoy the fireworks display.

The disorientation continued the next day at Bewartstein castle, where I heard (or at least I thought heard — the tour guide was speaking German, my relative translating bits and pieces) that the best wine was reserved for the king’s knights at the castle, because if the water supply was poisoned, they would survive to protect the king. This concept cast a whole new perspective on the purpose of, and fascination with, wine-making. Water fermented with grapes in the wine-making process would render it safe to drink.

The disorientation continued the next day at Bewartstein castle, where I heard (or at least I thought heard — the tour guide was speaking German, my relative translating bits and pieces) that the best wine was reserved for the king’s knights at the castle, because if the water supply was poisoned, they would survive to protect the king. This concept cast a whole new perspective on the purpose of, and fascination with, wine-making. Water fermented with grapes in the wine-making process would render it safe to drink.

A week later, at Heidelberg Castle, I encountered the world’s largest wine barrel, the Heidelberg Tun. The barrel was built as a kind of “reservoir” — 55,345 gallons in all — to contain wine quotas, that is, the royal family’s taxes on wine growers under their rule. Imagine: all those wines dumped together in one enormous vat. What would be the point? Unless maybe, the water quality was poor, so the wine served as a substitute, or was mixed with mineral water to stave off illness?

A week later, at Heidelberg Castle, I encountered the world’s largest wine barrel, the Heidelberg Tun. The barrel was built as a kind of “reservoir” — 55,345 gallons in all — to contain wine quotas, that is, the royal family’s taxes on wine growers under their rule. Imagine: all those wines dumped together in one enormous vat. What would be the point? Unless maybe, the water quality was poor, so the wine served as a substitute, or was mixed with mineral water to stave off illness?

Which makes more sense, except for the dance floor on top of the barrel. Perhaps the royal family’s motives were not entirely pure.

I did not realize this book was so rare. My relative Angela gave a copy to me–Pfälzer in Amerika (Palatines in America) by Roland Paul and Karl Scherer–to help in my thesis research. Searching out a link to it for this blog, I notice it sells for a high price. I can see why.

I did not realize this book was so rare. My relative Angela gave a copy to me–Pfälzer in Amerika (Palatines in America) by Roland Paul and Karl Scherer–to help in my thesis research. Searching out a link to it for this blog, I notice it sells for a high price. I can see why.

It’s not such a big volume, but it’s packed with cross-cultural historical info. Published in 1995 by the Institute of Palatine History and Folklife, it offers articles about 18th and 19th century immigration to America from the Palatine region. Most of the text has English translations. Included are maps and explorations of the “waves” of immigration and their causes, bios of notable personalities, and letters written by immigrants to America (only in German).

I find the bios especially intriguing. I had not realized that Thomas Nast (b. 1840), “cartoonist, moralist, and ‘president-maker'” was a contemporary of Michael Harm (b. 1841).

When in Germany, I visited Villa Ludwigshöhe above Edenkoben, and walked through that town, but missed the part of Edenkoben with the Johann Adam Hartmann fountain. Born in Edenkoben, Johann Adam Hartmann emigrated in 1764 to America, finishing his days in Herkimer, NY. A neighbor of James Fenimore Cooper, many claim the main character of Cooper’s most famous series (Last of the Mohicans, The Deerslayer, The Pioneers, etc.) is in part based on Hartmann. Pfälzer in Amerika states:

[After arrival in America in 1764], Hartmann became a woodsman and hunter on the Indian frontier. When the War of Independence began in 1775, he had already had ten years of hunting and fighting experience which he now put to use. In particular, he is said to have been instrumental in winning the Oriskany battle against the British troops and their Indian allies in the Mohawk Valley on 6 August 1777.

A memorial plaque has also been installed in the village. “In Edenkoben and elsewhere, it is firmly believed that next to Daniel Boone, the man from Edenkoben formed the most important model for J. F. Cooper’s character, Leatherstocking.”

To imagine one might write a “brief” history of the Palatinate seems grandiose, but I think Larry O. Jensen has done a pretty good job, in “Articles of Interest” in a 1990 issue of the German Genealogical Digest (Volume VI, No. 2). I summarize the contents of his article below.

To imagine one might write a “brief” history of the Palatinate seems grandiose, but I think Larry O. Jensen has done a pretty good job, in “Articles of Interest” in a 1990 issue of the German Genealogical Digest (Volume VI, No. 2). I summarize the contents of his article below.

The Palatinate? Known in Germany as the Pfalz (from the Latin term palatium meaning palace or castle). Also called the Niederpfalz, the Pfalz am Rhein, “Palatinatus inferior”, “Palatinatus Rheni”, Rheinpfalz, and Rheinbayern. Why so many names for one relatively small stretch of land along the Rhine River? Perhaps because this charming locality has seen a whole lot of history.

HISTORY OF THE PALATINATE

3rd century – Inhabited by Alemannic tribes

6th century – Conquered by the Franks, who established tribal districts, otherwise known as “Gauen”

9th century – Under Charlemagne, earls were established to rule the Gauen

12th century – King Friedrich I became the ruler.

1214 – Ludwig of Bavaria, of the House of Wittelsbach, became ruler of the Palatinate, by marriage

1410 – Four sons of King Ruprecht III divided the region into four parts. Ludwig III, the eldest, received the Rheinpfalz

1508-1544 – King Ludwig V introduced Protestantism, although he himself remained Catholic

1618-1648 – Thirty Years War. At the start, the Pfalz was ruled by King Friedrich IV, leading supporter of the Evangelical Union. In 1622 Heidelberg was conquered and plundered, and the Pfalz turned over to Bavaria’s Duke Maximilian. Spinola of Spain then invaded the Pfalz. The plague hit at around the same time, wiping out as much as two-thirds of the population. The Thirty Years War established the right of three religions to exist: Catholic, Lutheran, and Calvinist.

1673-79 – War between the German Empire and France, in which the Pfalz had to pay 250,000 florin in war tax. (1683, Pietists emigrate, establish Germantown, PA)

1688 – War of the League of Augsburg. King Louis XIV of France invaded and burned most of the region to the ground.

1697 – Treaty of Rijswik made the State Church Catholic, although Catholics were outnumbered 5 to 1.

1705 – Calvinist and Lutheran churches re-established.

1707 – Palatinate destroyed in the Spanish War of Succession. (1708 – another emigration led by Joshua von Kocherthal, many of whom settled in Neuberg on the Hudson River.)

1742 – The Palatinate grew and prospered in trade, agriculture, arts, and science.

1799 – France moved in to occupy the Palatinate, Napoleon officially took the region over in 1801.

1815 – Paris Peace Treaty gives the Palatinate to Bavaria. Thirteen districts were created: Bergzabern, Frankenthal, Germersheim, Homburg, Kaiserslautern, Kirchheimbolanden, Kusel, Landau, Ludwigshafen, Neustadt, Pirmasens, Speier, Zweibruecken

1832 – Hambacher Festival – enormous gathering of peasants and intellecuals from all over Europe at Hambach Castle to advocate for a democracy – the tricolor black, red and gold flag was first flown. The rulers quickly put down the movement, and forbid political assemblies.

1849 – Democratic Revolution of 1848 crushed by Prussia and Bavaria (prompting a wave of emigration from the region)

1871 – The Palatinate joins the united German Empire.

There are many twists and turns in between, but were I to include them, this history would not be brief. Not at all. When I visited the Palatinate a little over a year ago, a member of the Bad Dürkheim history club noted they had suffered more than 20 wars between 1610 and 1850. No wonder the Spätlese (late harvest wines) are so popular — no doubt they take off the edge. These days, the people of the Palatinate are a fun-loving people, in a fertile, enchanting land.

There are many twists and turns in between, but were I to include them, this history would not be brief. Not at all. When I visited the Palatinate a little over a year ago, a member of the Bad Dürkheim history club noted they had suffered more than 20 wars between 1610 and 1850. No wonder the Spätlese (late harvest wines) are so popular — no doubt they take off the edge. These days, the people of the Palatinate are a fun-loving people, in a fertile, enchanting land.

I am home safely.

On Saturday, I had the opportunity to harvest grapes the old-fashioned way, by hand, with local Freinsheimers. Then, on Monday morning, just as my suitcases were being loaded into the car, the local Die Rheinpfalz newspaper arrived at Barbel’s door. And there I appeared, in the local news section, page 2.

“Search for roots leads to vineyard: In the city vineyard, American author from Seattle assists in her grape harvest debut ” etc. etc. and a few paragraphs later, the following text:

Posted in Travels in Germany