To imagine one might write a “brief” history of the Palatinate seems grandiose, but I think Larry O. Jensen has done a pretty good job, in “Articles of Interest” in a 1990 issue of the German Genealogical Digest (Volume VI, No. 2). I summarize the contents of his article below.

To imagine one might write a “brief” history of the Palatinate seems grandiose, but I think Larry O. Jensen has done a pretty good job, in “Articles of Interest” in a 1990 issue of the German Genealogical Digest (Volume VI, No. 2). I summarize the contents of his article below.

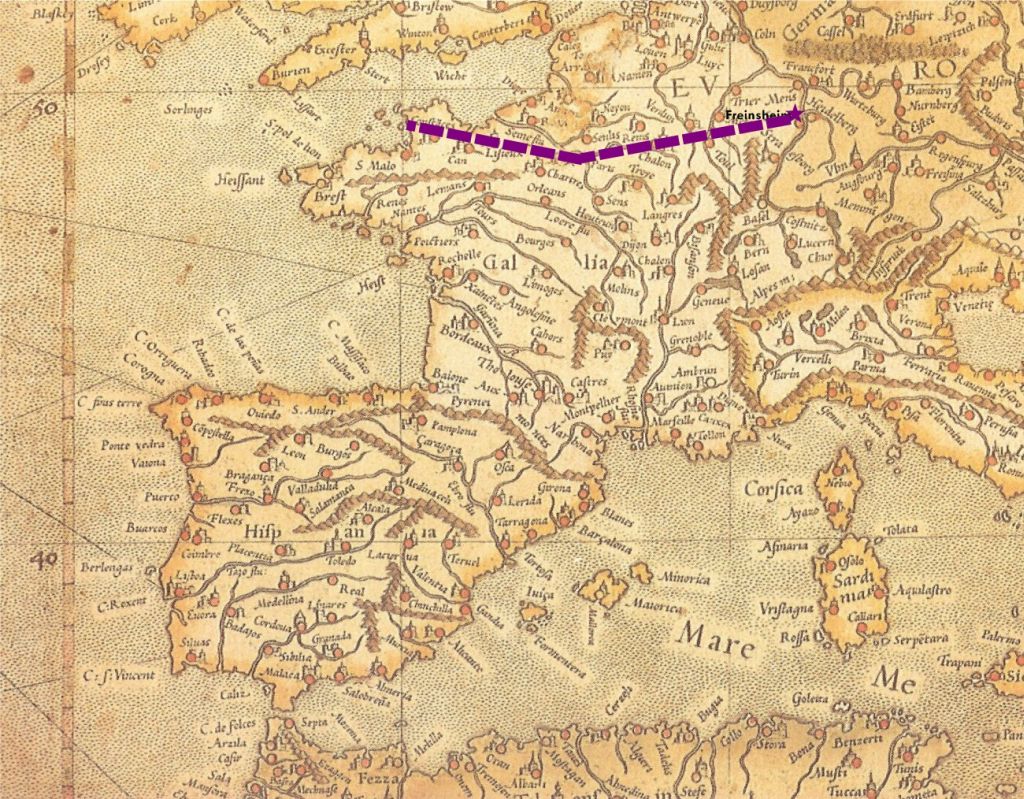

The Palatinate? Known in Germany as the Pfalz (from the Latin term palatium meaning palace or castle). Also called the Niederpfalz, the Pfalz am Rhein, “Palatinatus inferior”, “Palatinatus Rheni”, Rheinpfalz, and Rheinbayern. Why so many names for one relatively small stretch of land along the Rhine River? Perhaps because this charming locality has seen a whole lot of history.

HISTORY OF THE PALATINATE

3rd century – Inhabited by Alemannic tribes

6th century – Conquered by the Franks, who established tribal districts, otherwise known as “Gauen”

9th century – Under Charlemagne, earls were established to rule the Gauen

12th century – King Friedrich I became the ruler.

1214 – Ludwig of Bavaria, of the House of Wittelsbach, became ruler of the Palatinate, by marriage

1410 – Four sons of King Ruprecht III divided the region into four parts. Ludwig III, the eldest, received the Rheinpfalz

1508-1544 – King Ludwig V introduced Protestantism, although he himself remained Catholic

1618-1648 – Thirty Years War. At the start, the Pfalz was ruled by King Friedrich IV, leading supporter of the Evangelical Union. In 1622 Heidelberg was conquered and plundered, and the Pfalz turned over to Bavaria’s Duke Maximilian. Spinola of Spain then invaded the Pfalz. The plague hit at around the same time, wiping out as much as two-thirds of the population. The Thirty Years War established the right of three religions to exist: Catholic, Lutheran, and Calvinist.

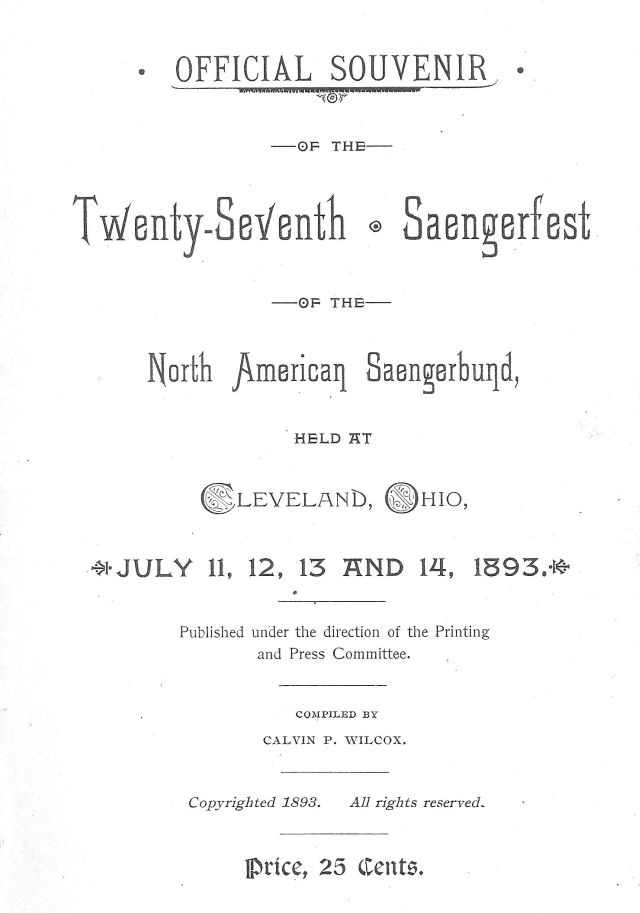

1673-79 – War between the German Empire and France, in which the Pfalz had to pay 250,000 florin in war tax. (1683, Pietists emigrate, establish Germantown, PA)

1688 – War of the League of Augsburg. King Louis XIV of France invaded and burned most of the region to the ground.

1697 – Treaty of Rijswik made the State Church Catholic, although Catholics were outnumbered 5 to 1.

1705 – Calvinist and Lutheran churches re-established.

1707 – Palatinate destroyed in the Spanish War of Succession. (1708 – another emigration led by Joshua von Kocherthal, many of whom settled in Neuberg on the Hudson River.)

1742 – The Palatinate grew and prospered in trade, agriculture, arts, and science.

1799 – France moved in to occupy the Palatinate, Napoleon officially took the region over in 1801.

1815 – Paris Peace Treaty gives the Palatinate to Bavaria. Thirteen districts were created: Bergzabern, Frankenthal, Germersheim, Homburg, Kaiserslautern, Kirchheimbolanden, Kusel, Landau, Ludwigshafen, Neustadt, Pirmasens, Speier, Zweibruecken

1832 – Hambacher Festival – enormous gathering of peasants and intellecuals from all over Europe at Hambach Castle to advocate for a democracy – the tricolor black, red and gold flag was first flown. The rulers quickly put down the movement, and forbid political assemblies.

1849 – Democratic Revolution of 1848 crushed by Prussia and Bavaria (prompting a wave of emigration from the region)

1871 – The Palatinate joins the united German Empire.

There are many twists and turns in between, but were I to include them, this history would not be brief. Not at all. When I visited the Palatinate a little over a year ago, a member of the Bad Dürkheim history club noted they had suffered more than 20 wars between 1610 and 1850. No wonder the Spätlese (late harvest wines) are so popular — no doubt they take off the edge. These days, the people of the Palatinate are a fun-loving people, in a fertile, enchanting land.

There are many twists and turns in between, but were I to include them, this history would not be brief. Not at all. When I visited the Palatinate a little over a year ago, a member of the Bad Dürkheim history club noted they had suffered more than 20 wars between 1610 and 1850. No wonder the Spätlese (late harvest wines) are so popular — no doubt they take off the edge. These days, the people of the Palatinate are a fun-loving people, in a fertile, enchanting land.