Mary Biddinger, author of Prairie Fever, St. Monica, and O Holy Insurgency, has started a self-interview series called The Next Big Thing. I’ve been tagged to participate by the awesome memoirist and writing teacher Janet Buttenwieser, author of Guts.

What is the working title of your book?

What is the working title of your book?

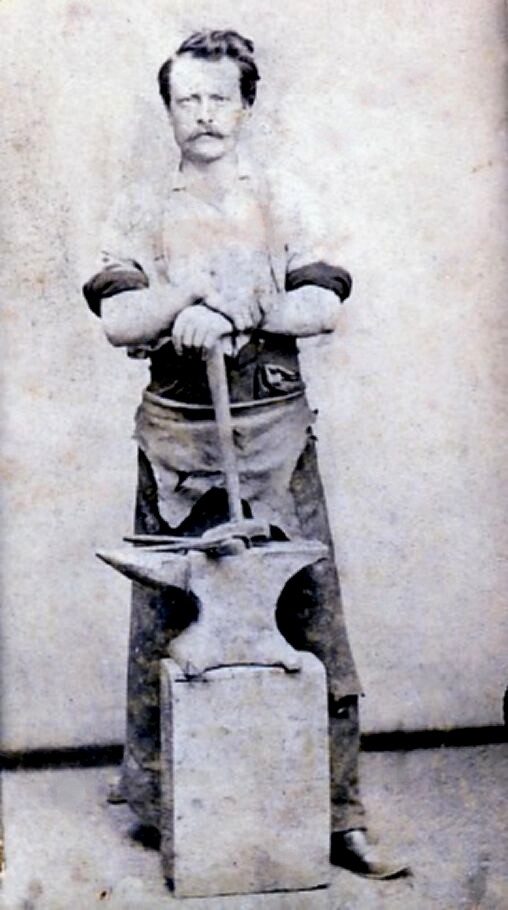

The Last of the Blacksmiths.

Where did the idea come from for the book?

Originally, I wanted to write a book based on several dozen letters in my family dating back to 1840, written by German immigrant blacksmiths and wagon-makers in Cleveland. The letter writers lived at a time when the city population was approximately one-third German. Since I had unique primary source material, I pondered making the book non-fiction. But every time I researched a clue in the letters, it led me to new layers of history – the “mean-spirited” monarchies of Europe, the recurrent bank failures in the U.S., the short-lived era of travel by canal, the apprenticeship system that had faded to non-existence by the twentieth century. I came to understand that my great-great-grandfather lived at a key point in the nineteenth century, when Cleveland was on the cutting edge of worldwide trade, westward expansion, the advent of modern technology, and the discovery of oil.

What genre does your book fall under?

In the end, I chose to write historical fiction, in order to create characters and scenes and dialogue, to flesh out history into three-dimensions. Even so, The Last of the Blacksmiths is based on a true story and real events.

What actors would you choose to play the parts of the characters in your book?

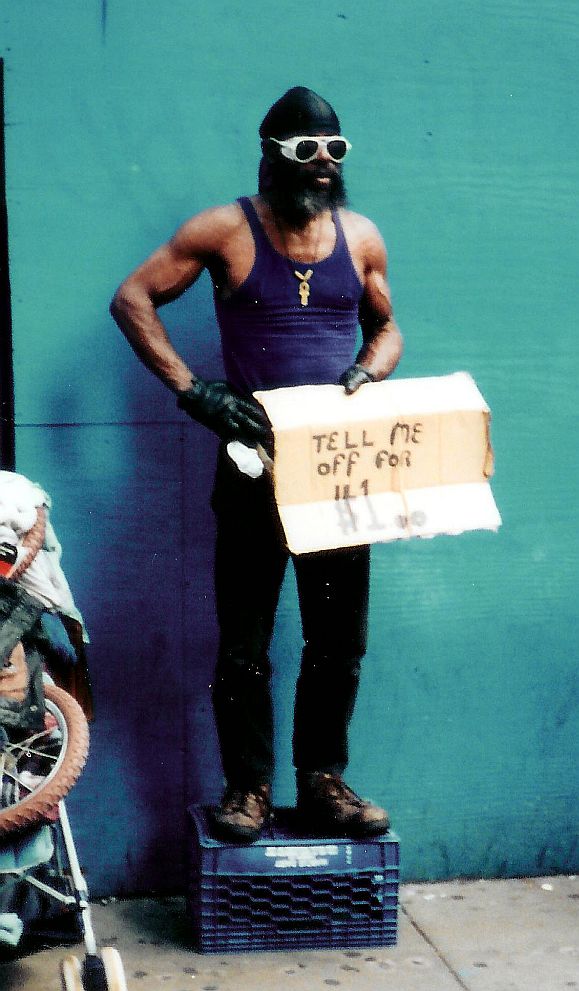

The German men would all have to be bearded and wear suspenders, like the Amish guys in the movie “Witness.” They would need to be broad-shouldered, too, what with all the blacksmith hammering.

CAST:

James Marsden — protagonist Michael Harm.

Ron Perlman — Singely, Michael’s fellow blacksmith apprentice. Or possibly Sean Astin, since Singely has no neck.

Bernard Hill — Johann Rapparlie, Michael’s master and antagonist.

Bradley Cooper — Charles Rauch, Michael’s rival in carriage-making and in love.

Jodie Foster – as a young actress, Jodie would have made an excellent Elizabeth Crolly, with her piercing eyes and strong set to her jaw. Hilary Swank would be a good choice, too.

What is a one-sentence synopsis of your book?

In 1857, Michael Harm leaves behind his family farm in the German Palatinate dreaming of wilderness, prosperity and freedom, to apprentice as a blacksmith in Cleveland, Ohio, wholly unprepared for what he finds—-strong prohibitionist and anti-immigrant sentiment, civil war, and an accelerating machine age that will wipe out his livelihood forever.

How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

About 18 months. I spent over a year in research alone. I had much to learn about history, like blacksmithing for instance. I took a four-day beginning blacksmithing workshop, which gave me a profound respect for this ancient artisan craft (and I forged a fireplace poker, besides). I wrote the first 150 pages or so in the first year, then had the opportunity to spend a month in Germany. My “research trip” (which involved much wine-tasting) was graciously hosted by my German relatives. They escorted me to museums and castles and on bicycle tours to Roman ruins, and also translated for me during meetings with German historians. It was awesome, and a humbling experience. When I returned, with so many new insights, I realized that despite my best efforts I’d been incredibly naive. So I tossed everything out and started over on page one, cranking out a full first draft in five months.

What inspired you to write the book?

With the discovery of the letters, previous assumptions about Cleveland (where I grew up), about my family’s past, about my understanding of the nineteenth century, all took on new meaning. To hear in the letters from the people who actually lived it was inspiring. I felt compelled to tell their stories. We live now in such a technological, material age. How did we get here? Much of it began back in the nineteenth century, a pre-petroleum era we know so little about.

What else about the book might pique the reader’s interest?

My protagonist, Michael Harm, witnessed some amazing moments in history: When he was only seven, his rural village in the Palatinate was occupied by Prussian troops who had come to crush a democratic rebellion against the feudal monarchies. At age 15, Michael arrived in New York City as a major riot broke out between the Irish and the police in the Five Points Slum. Almost as soon as he reached Cleveland, a financial crisis sank the country into a deep depression. He saw the new Republican Party and Abraham Lincoln rise to power, the onset of the Civil War with its tragic loss of life. Then came Cleveland’s “Gilded Age.” The book explores not just my ancestors, but the German American immigrant experience.

Will your book be self-published or are you being represented by an agency?

My book will be published in the coming year by Coffeetown Press. My release date is February 15, 2014 — I’m really excited for that day to arrive.

My tagged writers for THE NEXT BIG THING are Connie Hampton Connally, Don Crawley, and Sandra Sarr.