The Wiener Schnitzel legacy

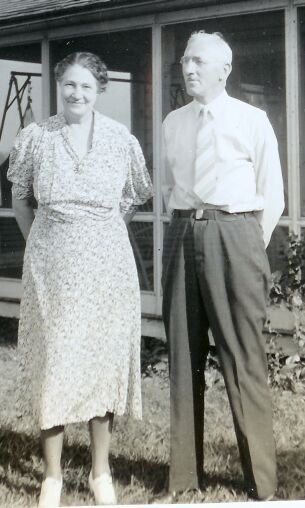

My grandmother Emma (center back in the photo) knew Michael Harm. He died when she was around nine years old. Grandmother used to tell me stories about him, how her grandfather suffered from gout at the end of his life, how he’d sit in the kitchen with stiff, swelling joints, her grandmother Elizabeth lining hot cloths along his legs to ease the pain.

My grandmother spent so much time with her grandparents, who still spoke German in their home, that she learned to speak German as a child.

This branch of the family tree, of my father’s maternal lineage, works out to five generations of separation. Michael and Elisabeth Harm (nee Crolly) begat Lucy Harm who begat Emma Hoppensack who begat Clyde Patterson who begat Claire Gebben. You see the first three generations pictured together here.

When growing up, I spent quite a bit of time with my grandmother. Now that I’m writing this thesis, I see those hours in a new light. I keep wondering: What uniquely German traits were passed to my grandmother via her German heritage? What habits? What ethics and ideas? What recipes? Ah, now we’re getting somewhere. The Wiener Schnitzel revelation.

In 1988, I traveled to Europe for a month, which included plans to visit Freinsheim. My work associate at the time had immigrated to the U.S. from Crailsheim in the Schwabian region. As luck would have it, Inge was planning to visit her mother in Crailsheim while I would be traveling in Germany. She invited me to stop in at her mother’s home. “She’ll make her Wiener Schnitzel for you,” my co-worker said. “It’s really great.”

I readily agreed, saying I’d never tried it before. So one evening in May of 1988, during my travels between Berlin and Freinsheim, I found myself sitting in the kitchen of my co-worker’s mother in Crailsheim, watching her put the finishing touches on her signature dish. At that moment, it dawned on me I’d been eating Wiener Schnitzel my whole life. I just knew it by different name: Pork Chops. My grandmother had instructed me, step by step, with great seriousness, on how to prepare what I now understand was an old German family recipe.

Harm family Wiener Schnitzel

4 pork chops (1/2-inch thick slices, bone in is best)

1/4-cup flour

salt and pepper to taste

1/2-1 onion, sliced in rings

1 T. butter or margarine

Toss the 1/4-cup flour with the salt and pepper on a plate and dredge each pork chop in the flour until all sides are completely coated.

Melt the tablespoon of butter or margarine on med-high heat in a fry pan (large enough to hold four pork chops at once). Add the sliced onion, brown for 2-3 minutes. When onions are getting soft, push them to the sides and put the flour-coated pork chops in the bottom of the pan. (Add more butter if the fry pan is too dry.) Brown the pork chops on med-high heat for 5 minutes per side. When the second side is good and brown, add enough water to the pan so that it barely comes to the top edge of the pork chops. Bring the water to a boil, cover the pan, and lower the heat to simmer for at least 30 minutes. When pork chops are tender, remove to a platter and serve with the onion gravy on the side. (Goes great with mashed potatoes!)

Serves 4.