I first learned of Thomas A. Kinney‘s research on horse-drawn carriages when roaming around the The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. In the section on the Wagon and Carriage Industry, I discovered a fascinating write-up about the prevalence of German carriage-makers in Cleveland, Ohio in the 19th century. Dr. Kinney had written the article. The information supported what I was learning from the letters of my ancestor, Michael Harm, once a carriage-maker in Cleveland, and so I emailed Dr. Kinney to share with him my photos of Harm & Schuster Carriages. We have been in correspondence ever since. Recently, Thomas A. Kinney spoke at the International Carriage Symposium in Williamsburg, VA.

INTERVIEW WITH THOMAS A. KINNEY

Thomas A. Kinney is Associate Professor of History at Bluefield College in Virginia and author of The Carriage Trade: Making Horse-Drawn Vehicles in America (Johns Hopkins University Press). He earned a B.A. in History from the University of Maine, then went on to Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland to earn his M.A. and Ph.D., also in history.

How did you first become interested in the wagon and carriage industry?

My research specialty was the history of technology. I came from Maine, a state with deep roots in the timber industry, and from a family with some involvement in that as well as in woodworking. I wanted to research something to do with logging, the woodworking trades—something like that. Acting on a chance conversation with a fellow graduate student, I began investigating wagon and carriage making. This was a woodworking trade, which like most crafts, underwent the process of industrialization. I became interested in the craft-to-industry transition, and it appeared horse-drawn vehicle manufacture would be a good candidate for such a study. I wasn’t disappointed.

No doubt you found a whole lot more than you bargained for. The Carriage Trade does such a great job of exploring more than woodworking: blacksmithing, painting, trimming, the growth of the industry on the eastern seaboard and in the midwest. But you started with Cleveland?

Yes, my dissertation “From Shop to Factory in the Industrial Heartland” looks at the industrialization of wagon and carriage manufacture in Cleveland. I focused on Cleveland partly because that was where I was living, but also because it was an iconic Midwestern industrial city—-one I hoped would have sufficient sources for my study. The end result, my dissertation, explained how the craft of wagon and carriage making became a full-fledged industry there.

The thesis was not published in book form, but my research attracted the attention of Johns Hopkins University Press. On the basis of their interest, I ended up taking my dissertation’s interpretive structure and expanding the focus to include the entire United States—-in other words, several more years of research, in this case in Washington D.C. and New York. Johns Hopkins University Press published The Carriage Trade: Making Horse-Drawn Vehicles in America in 2004.

And you had a best seller on your hands …

Well, that would have been nice, but that usually doesn’t happen with research monographs. It was well-received–co-winner of the 2005 Hagley Prize in Business History, and I’ve received numerous compliments from readers and fellow historians since then. Most books on wagons and carriages concentrate on the vehicles themselves, an artifact-based focus. The Carriage Trade is the first to focus exclusively on how they were actually built, a manufacturing-based focus. I think this fills some significant gaps in our knowledge of horse-drawn vehicles, but also in our understanding of nineteenth-century crafts and industry. So I’m pleased with it.

It filled in significant gaps in my knowledge. I was delighted to come across it in my research about my great-great-grandfather. Now, about the Third International Carriage Symposium, held at Colonial Williamsburg last month. What is this, and how did it get started?

The Carriage Association of America (CAA) is an organization of horse-drawn vehicle enthusiasts—-people who collect, restore, and drive wagons and carriages. Established in 1960, the association has sponsored driving events, competitions, tours of public and private collections, in addition to publishing an informative illustrated journal. They’ve always had an historical focus, but in 2008 they decided to try hosting a scholarly symposium where professional historians and museum curators could share new research on horse-drawn vehicles. Working in conjunction with the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, they held the first such event in 2008 at Colonial Williamsburg. They even started a journal, “World on Wheels,” to publish the papers. It’s become a well-attended event, held ever other year.

Who attends? Scholars? The general public?

The Carriage Symposium is a venue for scholarly research, and while some like myself are professional historians teaching at colleges and universities, others are museum curators, vehicle restorers, preservationists, and the like. But it is also open to the general public, whoever has an interest.

Colonial Williamsburg is an important contributor in a number of ways, not least of which are staff members who present on eighteenth-century carriages and related subjects. The CAA aims for an even mix of American and European presenters, the latter including historians and curators but also those in charge of horse-drawn vehicles owned by various royal families. The latter have fascinating hands-on experience with working vehicles in addition to a deep knowledge of carriage history. So the presenters come from a wide background, the common denominator being serious research on the history of horse-drawn vehicles.

There are also “horse people” who participate in competitive equine events, horse-drawn vehicle collectors both casual and advanced, and just ordinary individuals with an interest in historic transportation, horses, farm wagons-—that sort of thing. It’s a really worthwhile experience: first-class researchers from around the world, an engaging assortment of attendees, a marvelous conference setting, and the opportunity to not only see Colonial Williamsburg but also to take a behind-the-scenes looks at that vast operation.

And you spoke at this year’s Carriage Symposium, drawing from your research on commercial carriages? Business wagons and such?

Yes, I had the privilege to be invited to speak. I say privilege because it’s such a delight to speak to large audiences of people who are really interested in your work, and because both the Carriage Association and Colonial Williamsburg are such generous hosts. I spoke on horse-drawn commercial vehicles, focusing on their increasingly forgotten role in American cities. “Looking Back at Horse-Drawn Commercial Vehicles” draws heavily on my Cleveland research, both old and more recent, and I was pleased to include newly-identified photographs from the Smithsonian Institution as well as images from private collections. The Carriage Association will be publishing the conference papers as well as a summary of the event in their journal, but they’ve meanwhile posted some photographs on their blog.

I understand my great-great-grandfather made an appearance.

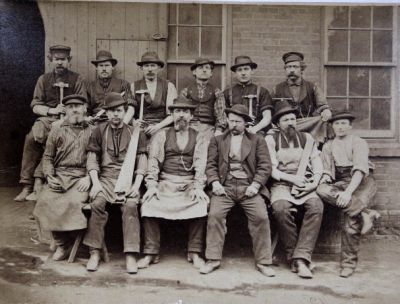

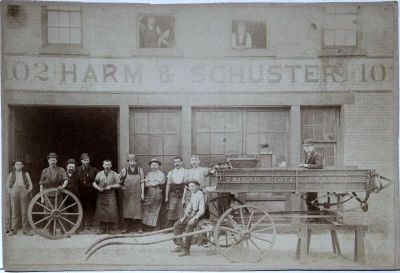

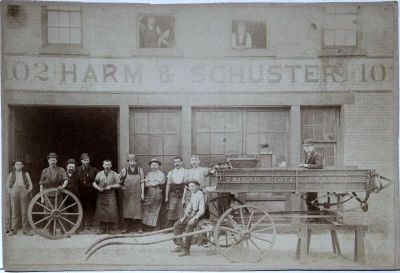

That’s right! One of the pleasures of publication is the unexpected letters one receives from readers who have something to share. I can’t say enough how thrilled I was to hear from you, a descendant of one of those Cleveland carriage makers I researched in graduate school. In the course of that project I studied more than a hundred small firms, and it’s funny, but the names still rattle around in my head: Jacob Hoffman, Kredo & Ott, J. J. Eberle, Schoonard & Dulin, Gustav Schaefer, Griese & Deuble, Jacob Lowman, Stoll & Black—-a veritable lexicon of European names. So  when you said “Harm & Schuster,” not only did I recognize it, I knew I had a file on it—-just like I do on dozens and dozens just like them. But while I had information from the trade literature, the only visuals I’d managed to locate were fire insurance maps. To see photographs of the outside of the shop and of the men who worked therein—-well, that’s just priceless. Like putting a face to a name you’ve known

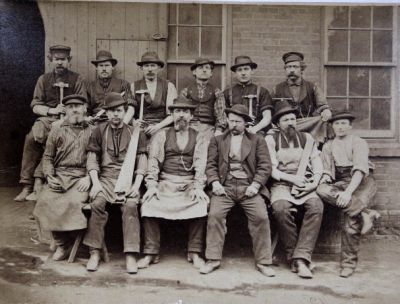

when you said “Harm & Schuster,” not only did I recognize it, I knew I had a file on it—-just like I do on dozens and dozens just like them. But while I had information from the trade literature, the only visuals I’d managed to locate were fire insurance maps. To see photographs of the outside of the shop and of the men who worked therein—-well, that’s just priceless. Like putting a face to a name you’ve known  for a long, long time. Since Michael Harm made commercial vehicles as well as passenger carriages, I used two of those images in my presentation: one of the workmen and proprietors holding representative tools of their trade, the other showing the shop hands around an express wagon. It looks like they’ve just finished resetting the tires and are about to remount the wheels. Great stuff, and a perfect example of the things that can happen when collectors and ordinary people share their resources with scholars. I spent years combing libraries and archives for material on the Cleveland trade, but I never found anything quite like what you shared with me.

for a long, long time. Since Michael Harm made commercial vehicles as well as passenger carriages, I used two of those images in my presentation: one of the workmen and proprietors holding representative tools of their trade, the other showing the shop hands around an express wagon. It looks like they’ve just finished resetting the tires and are about to remount the wheels. Great stuff, and a perfect example of the things that can happen when collectors and ordinary people share their resources with scholars. I spent years combing libraries and archives for material on the Cleveland trade, but I never found anything quite like what you shared with me.

Nice to hear. So what’s next? Are you working on another book?

I’ve been accumulating material on the Brewster companies for several years. In fact, at the first Carriage Symposium in 2008, my presentation was “Beyond the Builder’s Plate,” a look at Brewster carriages from a manufacturing standpoint. Carriages built by a couple of different firms of that name were some of the leading luxury brands in the trade, and they retain an avid collector interest today. I’m in the process of researching them for a second book. However, in order to write that I need to get back to New York to finish researching some important sources there. It’s a matter of obtaining grant money and such.

In the meanwhile, I continue to write on related subjects. I’ve just completed an article on the history of ready-made paint; that contains some information about the wagon and carriage industry as well.

Well then, you’ll want to hear about my grandfather, who worked at Sherwin Williams in Cleveland for fifty years — haha. Seriously, thank you for taking the time for this interview.

You’re most welcome. Thank you for taking an interest in my work and for sharing your rich family history. I think we all benefit from such collaboration.

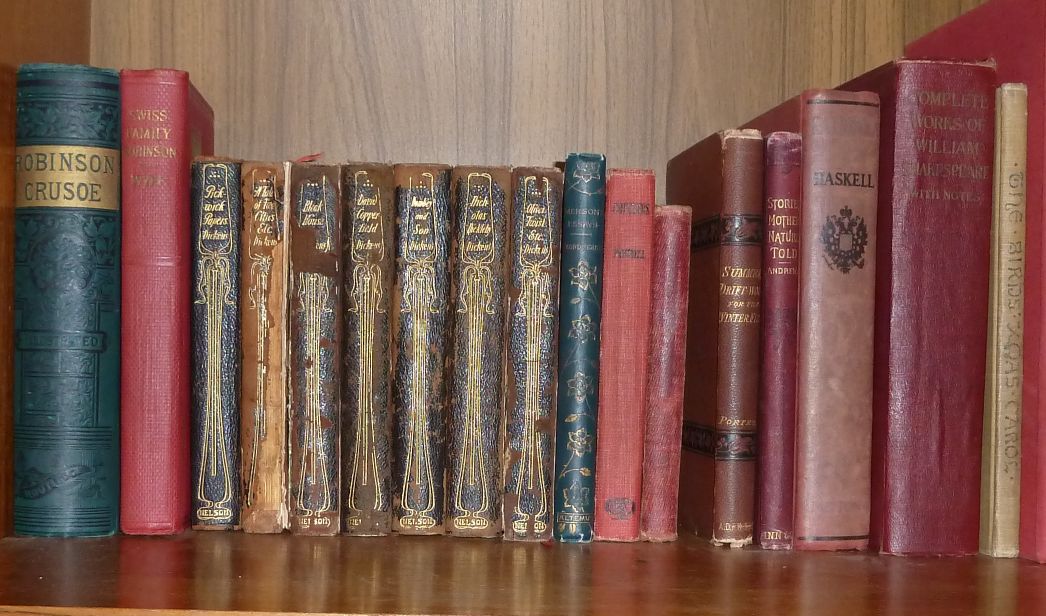

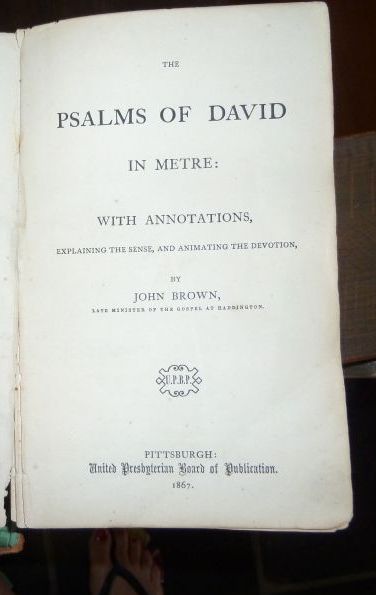

Old books can be like treasure hunts. In The Psalms of David In Metre I was captivated by the subtitle: With Annotations explaining the Sense, and Animating the Devotion, By John Brown, late minister of the Gospel at Haddington. This John Brown was an Anglican minister who lived from 1722 to 1787. It turns out he was a self-made man, a shepherd in Scotland who taught himself to read Greek, Latin and Hebrew. In the songbook in my possession, each Psalm of David begins with Brown’s notes about content and meaning.

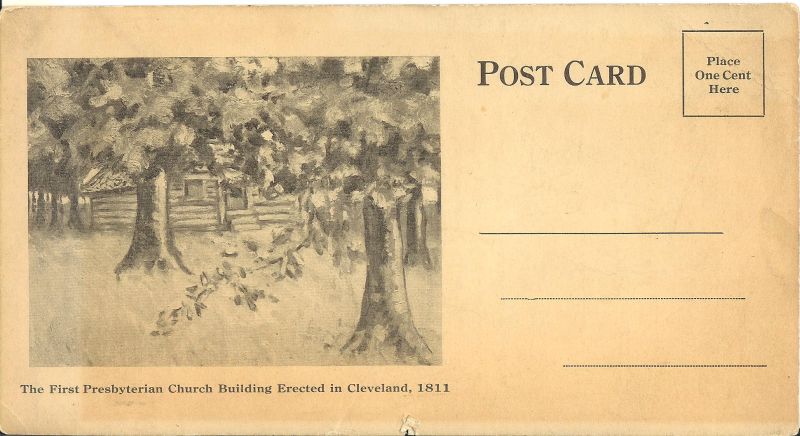

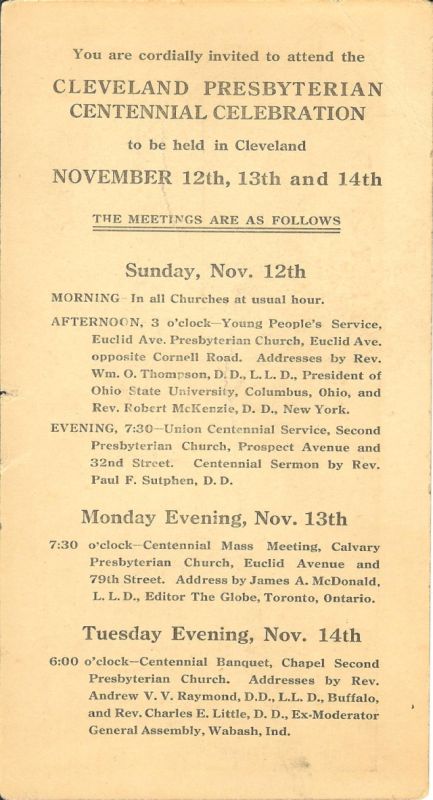

Old books can be like treasure hunts. In The Psalms of David In Metre I was captivated by the subtitle: With Annotations explaining the Sense, and Animating the Devotion, By John Brown, late minister of the Gospel at Haddington. This John Brown was an Anglican minister who lived from 1722 to 1787. It turns out he was a self-made man, a shepherd in Scotland who taught himself to read Greek, Latin and Hebrew. In the songbook in my possession, each Psalm of David begins with Brown’s notes about content and meaning. But there’s more. Tucked in the pages was also a postcard from 1911 advertising the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the First Presbyterian Church of Cleveland, founded in 1811.

But there’s more. Tucked in the pages was also a postcard from 1911 advertising the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the First Presbyterian Church of Cleveland, founded in 1811.