I have been listing the immigrants to Cleveland, Ohio, who lived long enough, or stuck around Cleveland long enough, to be listed in an anniversary edition of the Cleveland German newspaper “Wächter und Anzeiger.” The list goes through the start of the 1860s, and I will continue to type up the remaining years in future posts. In the meantime, there are several things I’ve figured out in my research that I want to share.

First, the immigrants listed in these posts are part of what is considered the “first wave” of immigration. (The “second wave” of over a million German immigrants in the U.S. occurred from 1865-1879, the “third wave” nearer the turn of the century, and so on.) In 1848, the immigrants to Cleveland listed total nine names. In 1849, they number twenty, over twice as many. It could be argued this is an example of chain migration, where first one family member arrives, and others follow, but only Müller of Alsenz seems to fit in this category. Other influential factors:

–In 1848, the California Gold Rush began. Perhaps some of these immigrants are part of this rising tide (by 1854, four times as many German immigrants to Cleveland are listed as in 1848).

–In 1848, starting in France in March, democratic revolutions swept across Europe, and many in the German-speaking areas (and Hungary, Austria, France, etc.) were forced to flee.

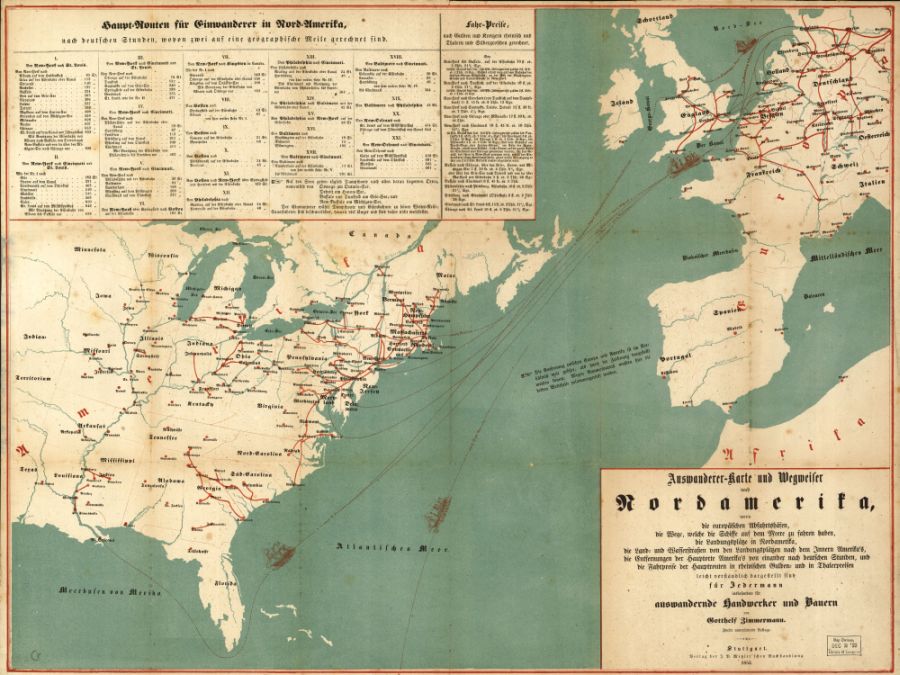

–By the early 1850s, transatlantic steamship crossings were more common, shortening the westward journey to around two weeks. However, in reality, most immigrants still traveled on sailing ships called “packets,” a crossing lasting around 40-50 days.

–Manufacturing: due to the steam engine, factories were driving many out of age-old trades like shoemaking and blacksmithing

–Farming: there had been almost a decade of lean years of bad harvests and crop failure (potato rot).

–Religious persecution: the faith of the prince of a duchy dictated the religion of its citizens. The U.S.’s constitution, declaring freedom of religion, was irresistible, to Catholics in some regions, Protestants in others, and across the board, to Jews.

–In most of these German-speaking regions, a man was not permitted to marry if he did not have property, a living, or craft guild membership.

–In the south and west, rising population increased economic pressure.

–Shipping companies bringing tobacco and sugar and other goods from the Americas conducted marketing campaigns to fill their cargo holds with paying European passengers for the return voyage.

–In Europe, the citizens paid taxes to the princes, dukes and kings. In the U.S., there were no taxes.

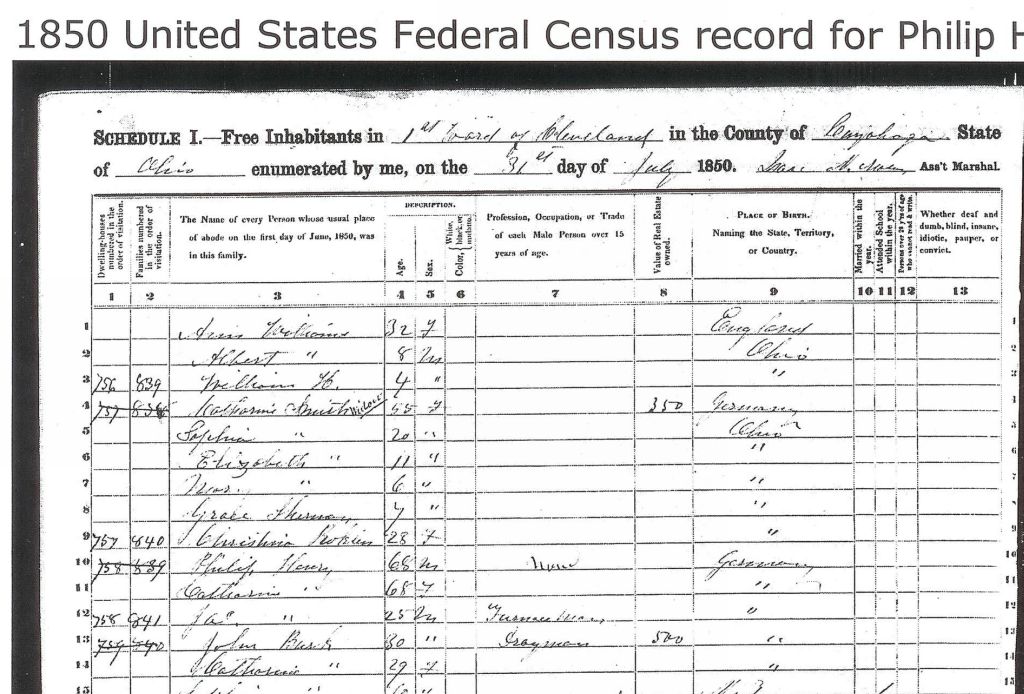

Second, note that these immigrants listed are mainly from a certain area of the German-speaking regions. This data follows national trends. In Stanley Nadel’s Ph.D. thesis on New York City’s Kleindeutschland, he notes: “Despite the slight lull during the revolutionary years of 1848-1850, the rising wave of emigration after 1843 carried nearly one-and-a-half million Germans to the United States before it broke over the rocks of depression and civil war in America. … The U.S. Census report for 1850 gives us a good idea of the origins of this wave of immigrants. Two-thirds of the German born residents of the United States were from the states of south and west Germany. Another 15% can be assigned to the Prussian Rhineland, making for a majority of over 80%.” (p. 35)