I admit I’m a history geek: Snowbound in Seattle, I can’t think of a better way to spend the day than curling up by the hearth fire with a just-discovered tome: Religion in American Life: A Short History, by Butler, Wacker and Balmer (2003).

Intended as an overview, the book begins with native religions and extends all the way into the Reagan and Bush eras of American conservativism.

Right now I’m buried in the chapter called “Reformers and Visionaries.” For example, William Miller’s numerology (mentioned in an earlier post: Is 2012 the end of the line?) led him to calculate the return of the Lord would occur in 1843. “[Miller’s] views reached a broad audience in Horace Greeley’s New York Herald, complete with illustrations. Comets and meteor showers at the time added to the excitement. Some said that Miller attracted thirty thousand to one hundred thousand followers.”

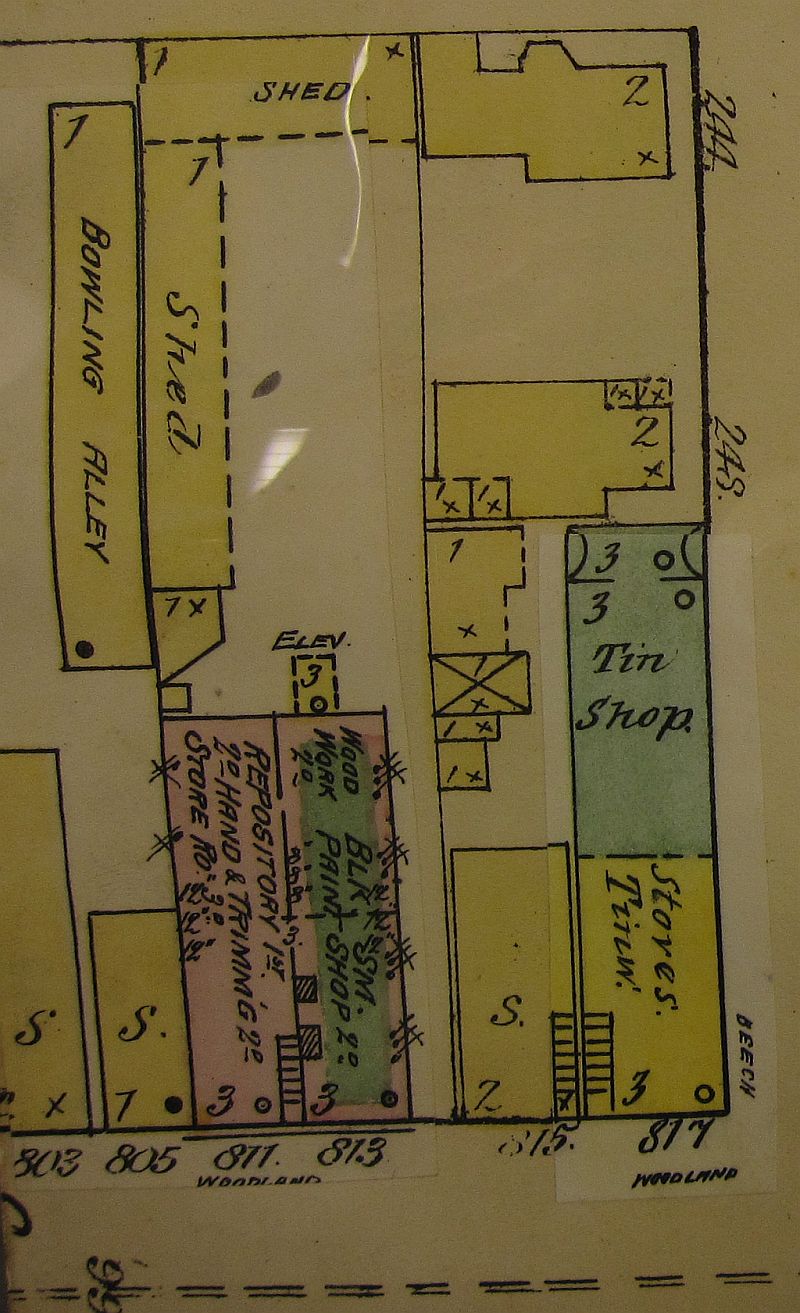

Another end-times religion began in the mid-18th century, due to the visionary zeal of Mother Ann Lee. Her sect came to be known as the Shakers. One of nineteen Shaker communities, the North Union Shaker Community was organized in 1822 on land just outside Cleveland, on property along Doan Brook.

Another end-times religion began in the mid-18th century, due to the visionary zeal of Mother Ann Lee. Her sect came to be known as the Shakers. One of nineteen Shaker communities, the North Union Shaker Community was organized in 1822 on land just outside Cleveland, on property along Doan Brook.

Better known as Shakers, members of the sect called themselves “Believers,” a shortened version of “the United Society of Believers in the Second Appearing of Christ.” Suffering persecution in England, a small band led by their founder, “Mother” Ann Lee, came to America in 1774. Ann Lee symbolized the second coming of Christ in female form, establishing the Shaker concept of sexual equality and of the deity as a father-mother God. Shaker colonies were founded in New York and the New England states, and later, on the frontier. (from The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History)

Today, the North Union Shaker Community is the neighborhood of Cleveland called Shaker Heights.