The “1848 Revolution” in Europe was a formative political event of the mid-19th century century. Beginning in late February, 1848 with an uprising in Paris, the foment of peasants against rulers played out across the many countries, duchies, and principalities of the day. It took over a year for all of the different revolutions to be crushed, the rebels scattered in exile. Here are a few persons who went on to make a name for themselves, who were active in some part of the 1848 struggles:

Richard Wagner was active in the rebellion in Dresden

Robert Schumann and his wife Clara were witnesses to the Dresden violence, and Schumann fled the scene rather than be conscripted in the city’s civil guard

Karl Marx was especially active in France in 1848; the failure of the rebellion convinced him of the need for a more radical society

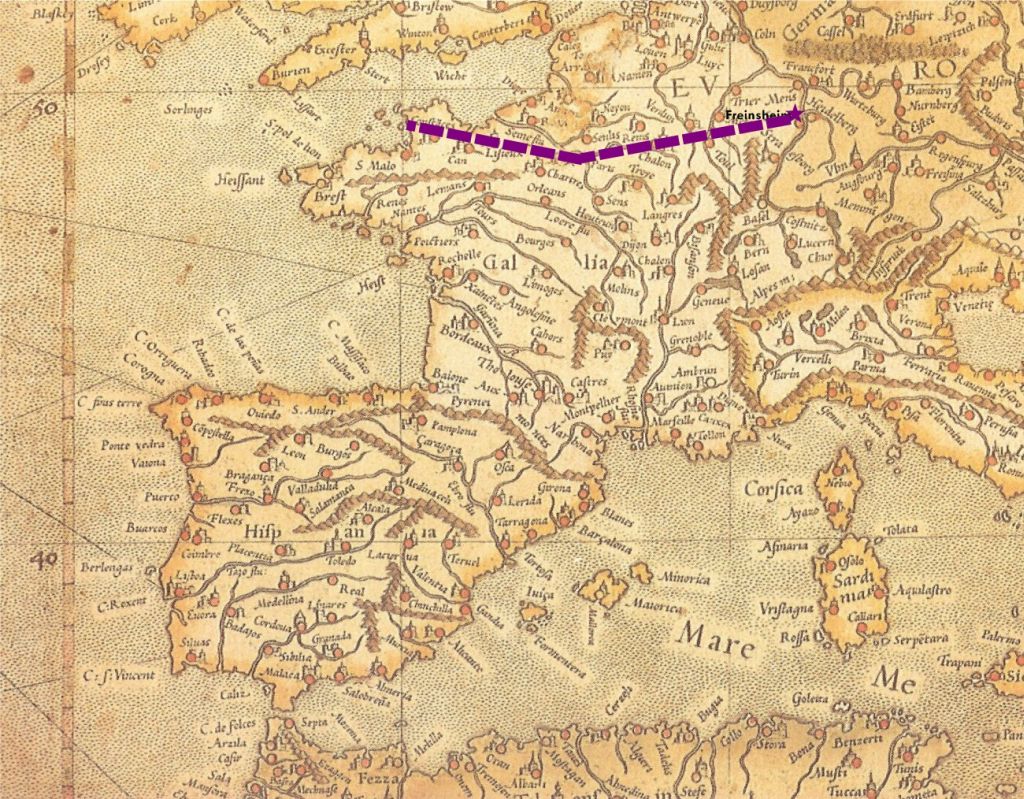

Frederick Engels wrote about his role in the Palatinate in 1849, in a document called “The Campaign for the German Imperial Constitution”

Otto von Bismarck was a young landowner who rose to power and influence on the monarchist side

Carl Schurz was a leader in the rebellious provisional governments army, who escaped from the Prussian troops through a sewer from a village under siege, sailed to America, and later became an active advocate of the newly formed Republican party and an attorney and friend of Abraham Lincoln

Jacob Müller was a provisional government civil commissioner of Kirchheimbolanden who immigrated to Cleveland, eventually becoming the tenth Lieutenant Governor of Ohio from 1872-1874.

Perhaps you know of others? If so, do tell.