To make things easier for blog visitors, I’ve been scrolling through my earliest blogs to add the following categories —

Cleveland and Ohio history, and

Freinsheim and Palatinate history

Just this morning, I came across a post from 2010 about the 19th century system of public education in the Palatinate known as the Volksschule. It’s very brief, based on my scant knowledge at the time.

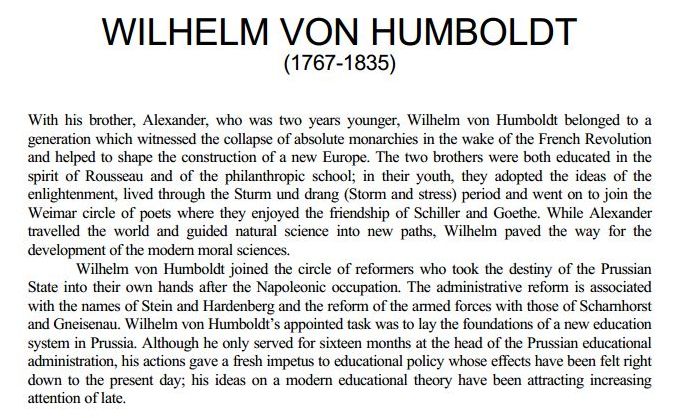

I’ve learned much more since then, especially about a couple of key figures of the 19th century — the Humboldt brothers. The full text of the article snippet pasted below, originally published in Prospects:the quarterly review of comparative education (Paris, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education), vol. XXIII, no. 3/4, 1993, p. 613–23. ©UNESCO:International Bureau of Education, 2000, can be found here:

At the Schiller institute, there’s a terrific overview of Wilhelm von Humboldt’s vision for education, in an article written by Marianna Wertz. A few of Humboldt’s views are excerpted below:

Philosophically, education has only three stages: Elementary education, scholastic [secondary] education, and university education. Elementary education should merely enable the child to understand and express thoughts, to read and write, and merely to overcome the difficulties involved in the major ways of describing things. … [The child] therefore has a twofold concern: first, with learning itself, and second, with learning how to learn. …

Scholastic education is divided into linguistic, historical, and mathematical studies … The student is ready to graduate once he has learned so much from others, that he is now able to learn for himself. …

… I also deny the possibility of purposefully setting up an essentially different establishment for future craftsmen, and it is easily shown, that the gap resulting from the lack of trade schools, can be completely filled by other establishments. …

Everyone, even the poorest student, would receive a full education, variously limited only in those cases where it could progress to further development; each individual intellect would be done justice, and each would find its place; none would need seek their vocation earlier than what their gradual development permits; and finally, most, even if they left school, would still have had some transition from simple instruction to practice in the specialized institutions.

Hence, by 1857, the year my great-great grandfather turned 15, there was a Volksschule system in place in the Palatinate where all children attended school until that age, regardless of whether they were destined for farming, the trades or a university education.

Remember how Latin was once a curriculum requirement in high school? Ever wonder where that came from? Humboldt continues:

And now, only a couple more suggestions on the learning of ancient languages. Proceeding from the principle that, on the one hand, the form of a language must become visible as form, and that this can happen better with a dead language, whose strangeness is more striking than our living mother tongue; and on the other hand, that Greek and Latin must mutually support each other, I would assert:

—That all students, without exception, absolutely must learn both languages in the elementary grades, whether it be both at once, or whichever one of the two is begun first. …

Hebrew … must be likewise strongly encouraged, not merely because of the theologians, but also because its grammatical and vocabulary structure seem at first to be radically different from Greek; are closely related to the language structures of primitive peoples; and therefore expand the concept of the form of language in general. …

The scholarly schools would admit no one who does not possess a firm foundation in elementary knowledge and is not at least nine years old. They would have five classes, and the elementary schools, two. …

Education in the elementary schools would comprise:

—reading,

—writing,

—mathematical relations and proportions,

—recitation exercises,

—the first and most necessary concepts of

human beings and the human species, of the Earth,

and of society,

—music,

—drawing,

—geography, history, natural history, insofaras they can yield material

which the mind can work on within the sphere assigned to each.

At its core, this whole system is based on the idea that, as the ancient Greeks believed, “nothing can be more important for our world than a comprehension of this characteristic feature … an uncommonly subtle feeling for everything beautiful in nature and art.”