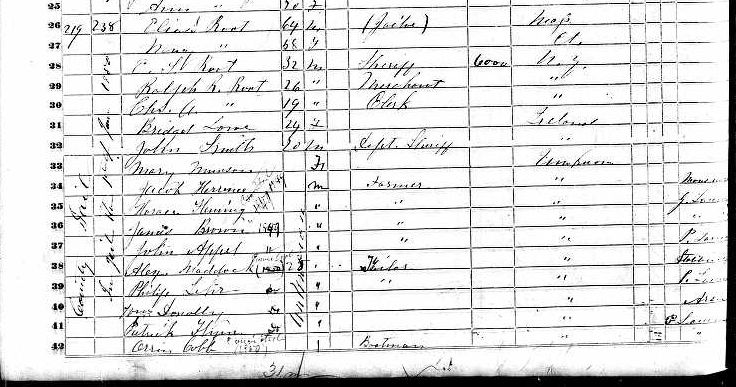

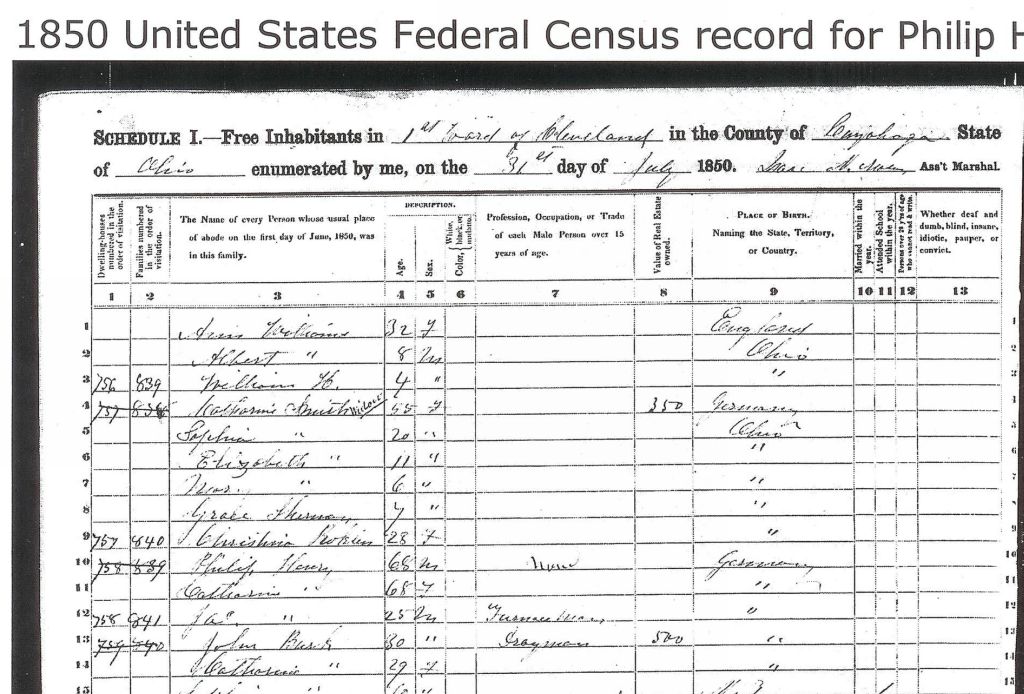

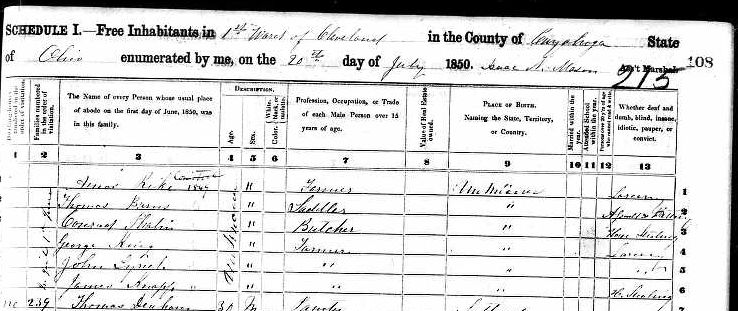

I was browsing Cleveland’s 1850 Federal Census Record on Ancestry.com, and figured out the jailhouse business in those days was a Root family enterprise:

Elies Root, 64, male, born in Massachusetts (jailor)

Nancy Root, 58, female, born in Ohio

E.S. Root, 32, born in NY, Sheriff, Real Estate value $6,000, born in NY

Ralph R. Root, 26, male, Merchant, NY

Charles Root, 19, Clerk, NY

Bridget Lowe, 24, Ireland

John Smith, Deputy Sheriff, Ireland

Cuyahoga County Jail residents:

Mary Munson

Jacob Herrince, farmer, murder? money counterfeiting? illegible …

Horace Fleming, farmer, g. larceny

James Brown, farmer, g. larceny

John Appel, farmer, p. larceny

Alex Maddock, tailor (sailor?), stabbing

Philip Lehr, g. larceny

Wm Donnelly, arson

Patrick Flynn, p. larceny

Orrin Cobb, boatman, p. larceny

Amos Rike, farmer, larceny

Thomas Burns, saddler, assault and battery

Conrad Phalin, butcher, horse stealing

George King, farmer, larceny

John Lynch, farmer, larceny

James Knapp, farmer, horse stealing

Places of birth for all convicts? “Unknown.” I’ll bet these folks had no idea how long their crimes would stick with them.