These days, it’s my understanding that men are primarily behind the distilling of whisky (Scottish spelling). I believed it had always been so until a few years back when I attended a storytelling session presented by the Seattle Scots Gaelic Society. The story (told to us by the seanchaichd (bard) in Gaelic, then repeated in English) went something like this:

There once was an old woman well-known for the fine quality of her whisky. She had just completed a small home batch when she happened to glance out the window and saw the village baillie and the excise man coming down the lane. Snatching up the bottle of whisky, she swaddled it in a baby tartan. When the men knocked on her door, she answered it cradling the “bairn.”

“Oh,” the baillie said, “I heard you’ve just become a grandmother. Congratulations. Let’s have a look at the wee bairn.”

“Shush, she’s sleeping, you mustn’t wake her,” the old woman said.

She invited the men in, but managed to distract them from their search by singing and cooing a sweet lullaby to the bairn in her arms. (Here the storyteller sang a song in Gaelic, about the bairn’s golden hair and warm, sweet qualities.)

The men left none the wiser, the old woman’s fine whisky spared.

At the end, we all enjoyed a good chuckle. The story also gave me pause. How odd, I thought. A woman distilling whisky in her home? Can that be right? Didn’t men build illicit stills in hidden nooks and crannies of the hills? This idea came from a visit to the Abriachan Forest in the Highlands, to a former illicit still dug into a hillside, neatly hidden from excise-collectors’ eyes.

At the end, we all enjoyed a good chuckle. The story also gave me pause. How odd, I thought. A woman distilling whisky in her home? Can that be right? Didn’t men build illicit stills in hidden nooks and crannies of the hills? This idea came from a visit to the Abriachan Forest in the Highlands, to a former illicit still dug into a hillside, neatly hidden from excise-collectors’ eyes.

Entrance to the hidden whisky still in the Abriachan forest

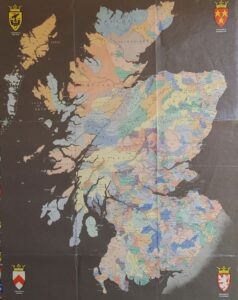

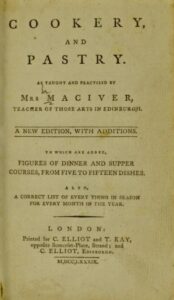

Recently, I happened upon a thesis by Sandra White titled “Smugglers and Excisemen: The History of Whisky in Scotland, 1644 to 1823.” Color me surprised, the story of the old woman was not odd in the least. It turns out whisky making in the Highlands used to be the woman’s job. “Uisge-beatha” or “water of life” is the Scots Gaelic term for whisky. Whisky was considered good for the health, especially in cold, damp climates. It was offered to visitors as a sign of hospitality. It was used as medicine, and in the making of herbal tonics. It was also an important source of income. “Housewives could sell excess whisky for cash, and whisky was also used to pay rents to landowners, to trade for other essential items, or to buy new farm equipment or animals.” Women took their whisky distilling responsibility seriously. Sandra White writes:

A woman was judged by her ability to produce enough whisky to keep her family and guests supplied throughout the year. When a marriage occurred in a community, the women were expected to provide enough whisky to flow throughout the evening. … Whisky was not intended to be consumed for inebriation. However, during social occasions, large quantities of whisky could be consumed in celebration to the point of drunkenness. And if there was not enough whisky for the entire evening, the women of the community were considered poor wives because it was part of their household chores to produce enough good quality whisky for all occasions.

This information does not seem to be widely known, another instance of the disappearance of the roles women have played in history. But not entirely lost. Check out this article about two women of the Cumming family who were instrumental in the success of Scotland’s Cardhu Distillery. Per Cumming family history, this account of one of Helen Cumming’s encounters with excisemen is not-so-weirdly similar to the old woman’s story recounted above.

‘On one occasion, when brewing, [Helen] was warned that [excisemen] were approaching. There was just enough time to hide the distilling apparatus, to substitute the materials of bread-making, and to smear her arms and hands with flour. When the knock came at the door, she opened it with a welcoming smile and the words: “Come awa’ ben, I’m just baking.’

[excerpted from an article by Richard Woodard found at Scotchwhiskey.com’s “Whiskey Heroes” section]

Helen’s ruse strikes me as especially clever — baking in the house would offer a plausible excuse for the steady smoke rising from her chimney. (Whisky making requires a constant heat source so the appearance of excess smoke was often a giveaway for the location of illicit stills in the Highlands.)

For more on women and distilling, there’s a book titled Whiskey Women: The Untold Story of How Women Saved Bourbon, Scotch, and Irish Whiskey about the influence of women in brewing and distilling from ancient (Mesopotamian) times to the present.

Happy New Year and cheers! Slàinte mhath!

Tinsmiths of the day were also known as tinkers, handy at most repairs. Upon further research, I turned up this book: Last of the Tinsmiths: The Life of Willie MacPhee by Sheila Douglas. In a nutshell:

Tinsmiths of the day were also known as tinkers, handy at most repairs. Upon further research, I turned up this book: Last of the Tinsmiths: The Life of Willie MacPhee by Sheila Douglas. In a nutshell: