It’s nice to have context. One day as I sat ruminating on the life of Michael Harm, the subject of my thesis project, it occurred to me to look up some people who lived in his era. Famous people who would have been his contemporaries.

Please understand, it’s not that I have delusions of grandeur for blacksmith Michael Harm, born in the German Rheinpfalz, who emigrated to Cleveland, Ohio and had a carriage making company. The list below, therefore, is only included as a frame of reference.

Michael Harm, 1841-1910

In the U.S.:

John D. Rockefeller, Sr., 1839-1937

Grover Cleveland, 1837-1908

Mark Twain, 1835-1910

In Europe:

Friedrich Nietzche 1844- 1900

Antonin Dvorak 1841 – 1904

Emile Zola 1840-1902

Claude Monet, 1840-1926

Karl May, 1842-1912

Hmm, you’re thinking — Karl May? But only if you’re from the U.S. If you’re from Germany, and you’ve never heard of Karl May you must have been born in the 21st century.

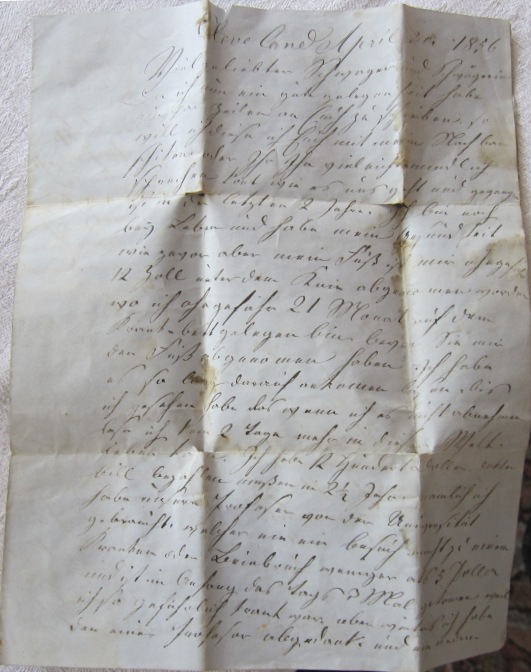

To me, Karl May is an interesting parallel to Michael Harm. One letter that traveled across the Atlantic from Cleveland back to Germany included a package with Indian moccasins, which Michael would have received when he was nine years old. This romantic fascination with the American Indian — could it be considered the “mythology” of the 19th century?