In 1866, Irish Americans, part of an organization known as the Fenian Brotherhood, hailing from Cleveland and other U.S. cities, invaded Canada.

The following are just a few snippets in the Annals of Cleveland, a compilation of Cleveland newspaper reports.

1866 Irish moving against Canada, amassing at borders of Buffalo and Detroit, to fight against Great Britain. Led by Sweeny, called Fenianism.

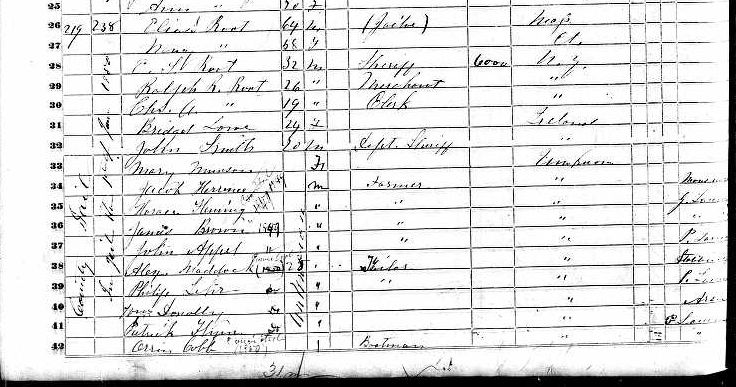

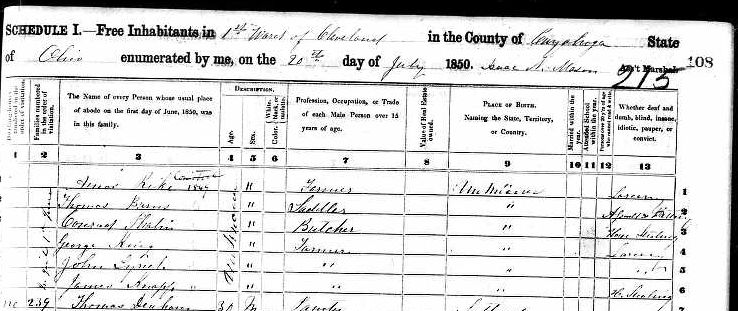

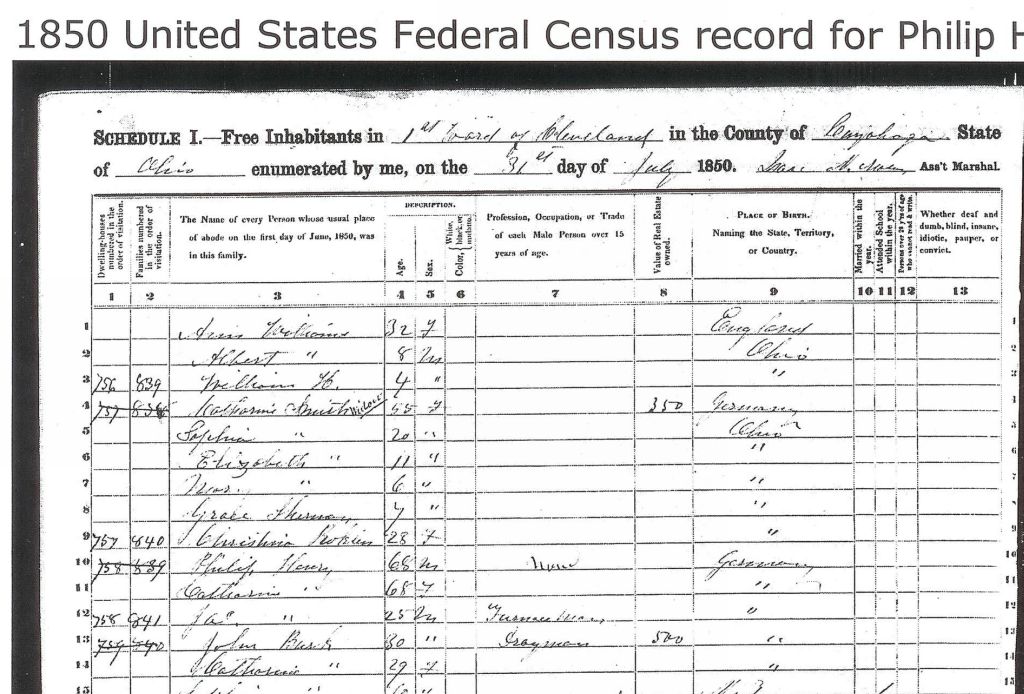

June 7: “In accordance with instructions received from the attorney-general of the United States, the officers of the Fenian brotherhood in [Cleveland] were arrested yesterday by U.S. Marshall Earl Bill on charges of aiding and abetting violators of the neutrality laws of the United States. The officers arrested were: Thomas Lavan, Thomas S. Quinlan, and Phillip O’Neil. The headquarters on Seneca St. were seized, and the papers, orders, etc. were taken

June 12, 15,000 Irish men “Fenians” were amassed along Canadian border from Potsdam Junction and Malone to St. Albans. British troops that met him numbered twice his army, resulting in an utter rout. Speech by Colonel Roberts, Fenian president, at Weddell house on July 3.

Trial of Fenians in Toronto – Cleveland Leader [newspaper] advocates for pardon, says hanging will bring more attempted invasion.

Apparently, there were more invasions, on into the 1880s. For starters, read all about it here.