A song that is formative for one generation becomes lost in obscurity for the next. That is the way of things, Grasshopper. (If you’re wondering, “Grasshopper” references a 1970’s TV program called “Kung Fu.”)

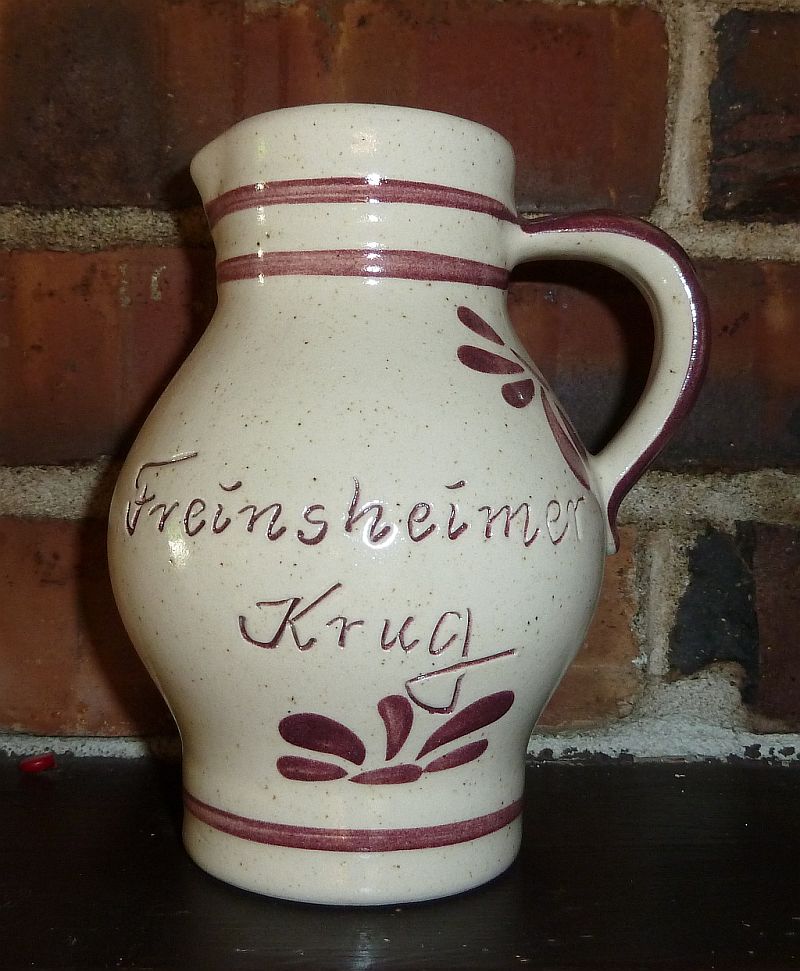

I visited Freinsheim, Germany last year at this time, to see my relatives, to do research, and to experience the Weinwanderung, a 7-mile culinary and wine-tasting hike through the vineyards. It’s awesome! This fall’s Weinwanderung dates are September 23-25. If you can swing it, you should definitely go.

Another memorable event during my trip last year was a meeting with Roland Paul (google translate link: click on “Autor”), Research Fellow and Deputy Director of the Institute for Palatine History and Folklore in Kaiserslautern. He has compiled the largest migration file index in Germany.

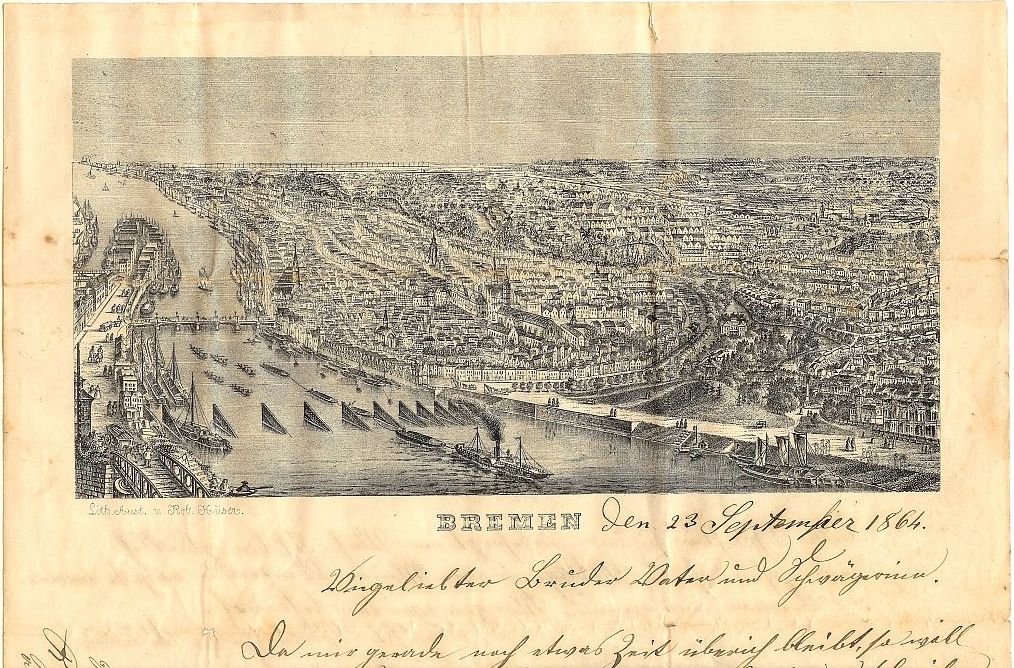

As we talked, I told him the working title of my thesis, which was “Something to Tell About” based on the quote by Matthias Claudius: “Wenn jemand eine Reise tut, so kann er was erzählen.” (When someone goes on a journey, then he has something to tell about.) Dr. Paul nodded perfunctorily. “Yes, yes,” he said. “This is a very popular quote in Germany.” Yet from my side of the Atlantic, I had come up with something pretty obscure.

The same thing happened when I mentioned the many immigration songs and poems. Dr. Paul nodded, waved his hand with a flourish. “Yes, Konrad Krez and so forth.” It hit home again, how what is so well known in one place or time can be so quickly forgotten in another. For general posterity, therefore, I post a poem by Konrad Krez, a moving ode to the immigrant’s journey (this version comes from the reprint of Jacob Mueller’s Memories of a Forty-Eighter (1896), translated by Steven Rowan).

Renunciation and Consolation

by Konrad KrezI dreamed in my youth

Of the roll of drums, the blare of trumpets,

Of the clatter of swords and the fire of muskets,

Of heroism and immortality,

And sick with fever I raised my hand

To pluck garlands from the tree of fame,

I burned for deeds to mark

My trail forever in the sand of time.It drove me to foreign zones,

My hills were too flat at home,

The valleys too narrow, the Rhine a brook,

I wanted alps, seas and waves.

I wanted to defy storm and hurricane,

See the splendor of the tropics with my own eyes,

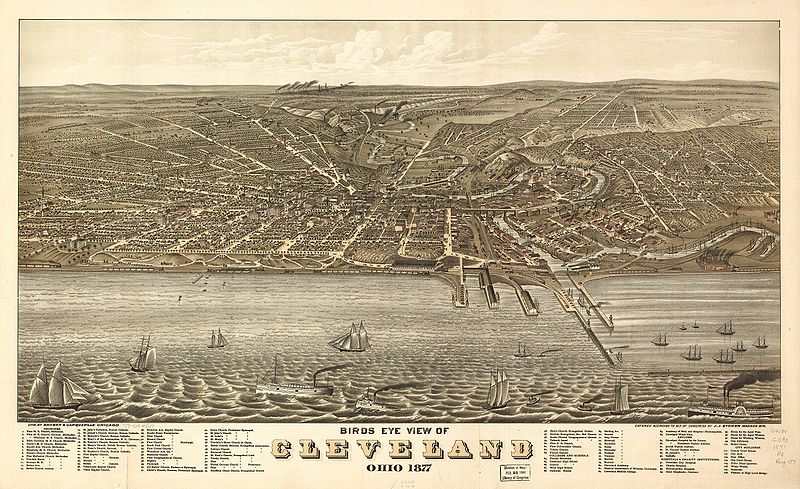

Head west, to the new Canaan,

And plant corn and wheat on the Ohio.And everywhere, wherever I came and went,

I found an ache, no land was so lonely

That I did not find there the way of care,

Even where no tree would grow, there was still distress,

Whether you go South or North,

East or West, to all the winds,

You will always find the same password,

The care of labor and work.The same struggle for daily bread,

Which does not deserve to be so hard earned,

Awaits you on the Hudson as on the Rhine,

Your rights include suffering everywhere.

And if you, through long years of effort,

Pile up riches, where will a whole heap

Of gold buy you a physician who knows a way

To buy back even a day of youth?To be sure you might be tempted to travel

The raw path of fame, to raise

A monument against forgetfulness, spiting envy with

Eternal praise by means of a famous deed;

Yet soon your ambition, your drive for fame

Will sink its wings with satiety,

When you spy the gates which beckon

When you go to drink of immortality.And if one kingdom was once too small for you,

Soon an acre of land will do,

A protecting roof, a log in the fireplace,

To be happier with wife and child

Than a tyrant whose whims pass through wires

To the limits of the earth,

But whom not even a subservient senate

Can resolve to heal him of death.Even if your burden presses and bends you,

And even if your heart distresses you,

Be consoled that life is not long,

And the path you have to go is short.

Then comes death and knocks on your door

As he did for your father,

Arriving like an old friend of the family,

And later he will visit your children.He speaks to you: My friend, you have dreamed,

Fought and worried, now it is time

To rest, your bed is ready,

I have arranged a private house for you.

You will obey and expel your breath into the wind.

Whether grass or marble covers your grave,

On it is written: Vain are

Things, and life is but a shadow.