My ancestor Michael Harm emigrated from Germany to the U.S. in 1857. During my research of the time period, I’ve discovered a number of “big events” occurring that year.

– July 4th riots in the Five-Points slum of New York City, a Democrats v. Republicans squabble over who controlled the city, including control over liquor laws.

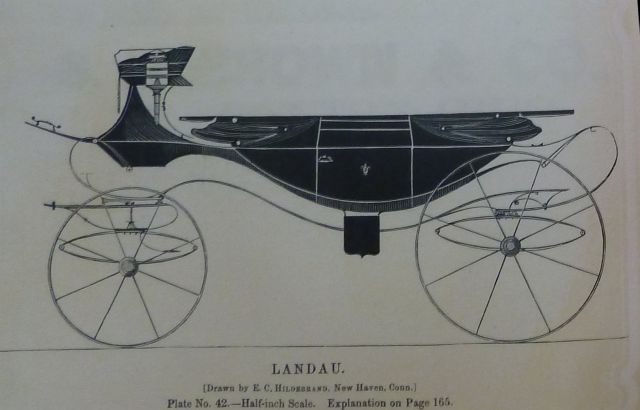

– On August 24th, railroad stocks tumbled, kicking off the financial Panic of 1857, further exacerbated by the sinking of the “Central America,” a ship loaded with federal gold to back up the U.S. treasury.

– Transatlantic telegraph cables were laid from North America to the United Kingdom for the first time. The first signal was feeble at best, then failed altogether a short time later. The first successful instantaneous communication across the Atlantic would not occur until after the Civil War.

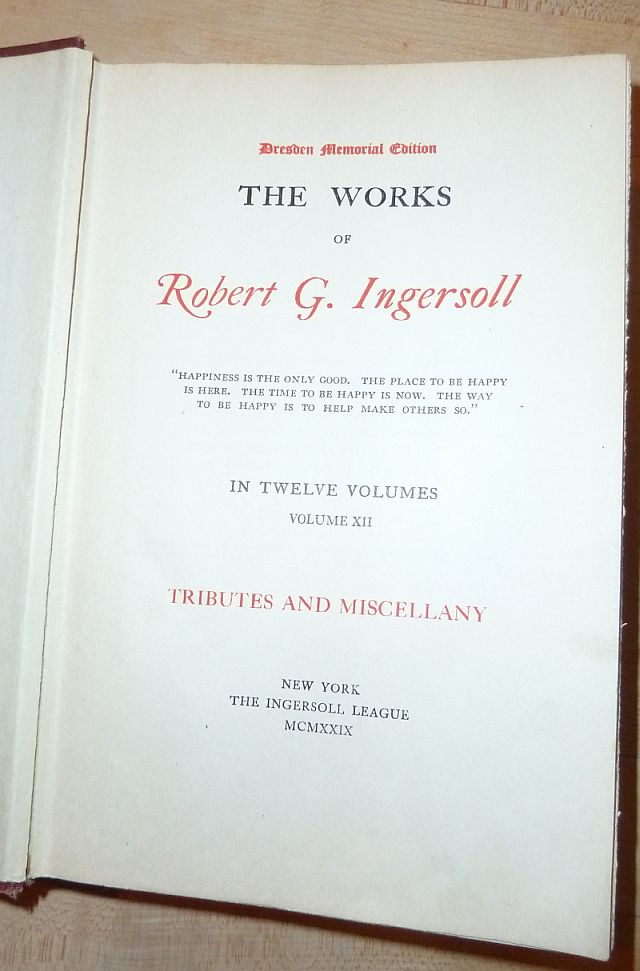

– The Atlantic Monthly was founded. I learned this the other day in the grocery story, when I plucked off the magazine shelf a special issue of articles published in the Atlantic on stories of the Civil War. It is an issue in honor of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War about the mid-19th century discussion of slavery, and includes essays by Louisa May Alcott, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., Nathaniel Hawthorne, and the first editor, James Russell Lowell. Here is an excerpt about the history of the magazine, given by Cullen Murphy at a 1994 presentation:

The year was 1857. Railroads did not yet cross the North American continent, but everyone knew that one day soon they would. The publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species was two years away, but loud rumblings in the halls of science had already warned the keepers of religious faith that serious challenges lay ahead. The largest wave of immigration in the nation’s history was pouring through the cities of the eastern seaboard. Though he would become President in four years, Abraham Lincoln in 1857 was no more widely known nationally than any former one-term Congressman is today. But the clouds of secession had begun to gather, and few believed that North and South, still joined by weak bonds of vexing compromise, would not soon be torn asunder.

Among educated people throughout the United States the issue of slavery was obviously one of great moment. But so, too, was another matter, and in the baldest terms it might be said to have involved an attempt to define and create a distinctly American voice: to project an American stance, to promote something that might be called the American Idea.

It was this concern that brought a handful of men together, at about three in the afternoon on a bright April day, at Boston’s Parker House Hotel. At a moment in our history when New England was America’s literary Olympus, the men gathered that afternoon could be said to occupy the summit. They included Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and several other gentlemen with three names and impeccable Brahmin breeding—men from the sort of families, as Holmes once noted wryly, that had not been perceptibly affected by the consequences of Adam’s fall. By the time these gentlemen had supped their fill, plans for a new magazine were well in hand. As one of the participants wrote to a friend the next day, “The time occupied was longer by about four hours and thirty minutes than I am in the habit of consuming in that kind of occupation, but it was the richest time intellectually that I have ever had.” Soon the new magazine acquired an editor, James Russell Lowell, and a name—The Atlantic Monthly.