Oh my! the book How We Survive Here has been out for a year now, and it’s been a wonderful ride. It’s always nice to hear from readers. Several people have commented to me, “It’s a great read. I was right there with you the whole way.”

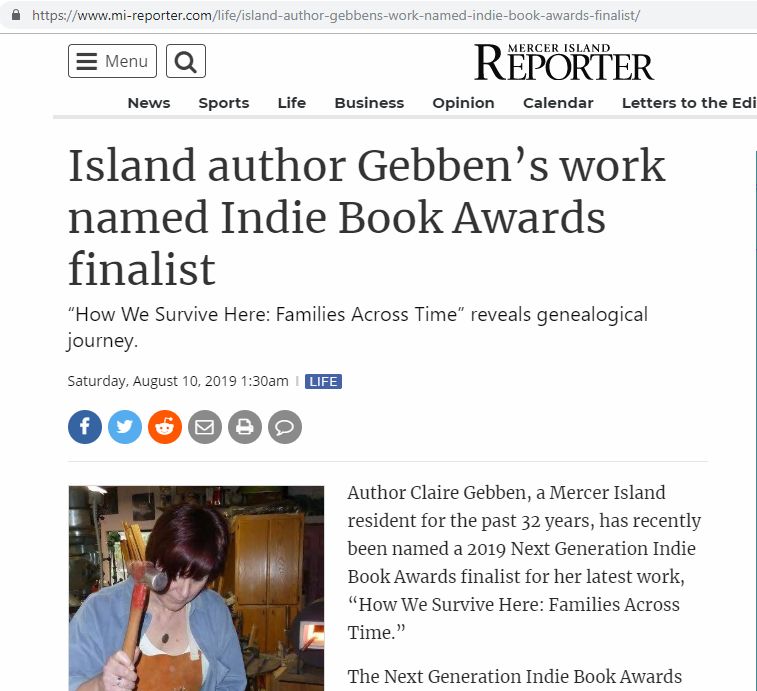

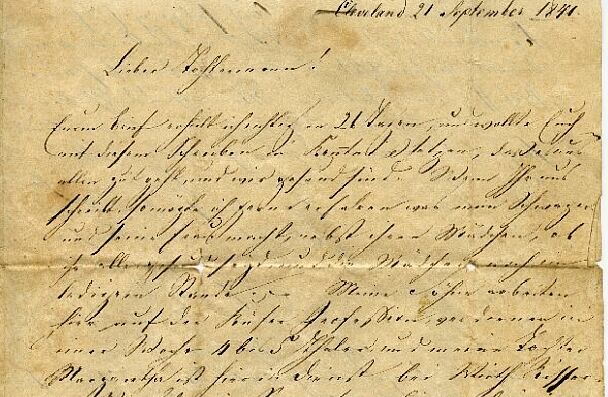

The book is the story of my quest to trace and write about my ancestors, which culminated in the historical novel The Last of the Blacksmiths (2014). In addition to being a memoir, the book How We Survive Here also includes letter translations by my German cousin, Angela Weber, making the letters available for the first time to genealogists and scholars.

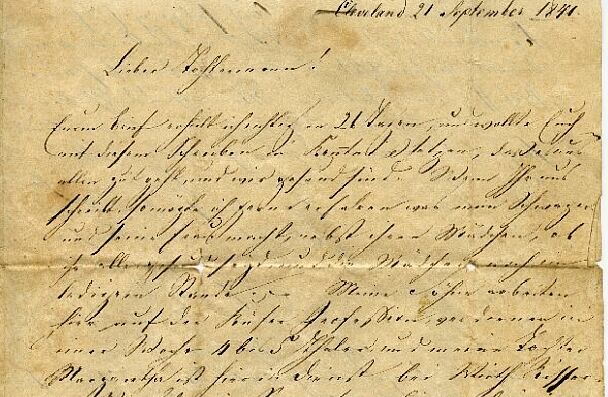

The letters were written in Old German Script, the cursive used in many German nation states up until the early 20th century.

Dating between 1841 and 1908, the letters are written from Cleveland to Freinsheim, Germany, by Philipp Henrich Handrich (1), Jakob Handrich (1), Michael Harm (23), Michael Höhn (1), and Johann Rapparlie (7). So many other surnames are mentioned. German immigration to Cleveland in the 19th century is a prime example of chain migration. After the first people came and got established, others from the same village followed.

In the back of How We Survive Here, I’ve included an index with page numbers noting where various names are mentioned. Below is the complete list of names.

Aul, Jacob / Aul, John / Aul, Philipp

Bender, Konrad

Beringer, Ana / Beringer, Georg and Jakob

Bletschers (see also, Pletschers)

Böhl, village of

Borner, Franz, Joseph and Ana

Butler, Ernst

Crolly, Adam / Crolly, Elizabeth (Harm) / Crolly, Gerhard / Crolly, Katherine

Dackenheim, village of

Dietz, Friedrich

Dürkheim/Bad Dürkheim, village of

Filius

Fischer, Ana

Försters

Francke

Freinsheim, village of

Frey

Fuhrmann, Johannes

Gonnheim, village of

Gros, Franz Wilhelm

Haenderich. See Handrich

Handrich, Philipp / Handrich, Jacob / Handrich, Jakob / Handrich, Johannes / Handrich, William

Handrich, Anna (Steinbrick)

Handrich, Katherina (Ohler)

Handrich, Katherina (Rapparlie)

Handrich, K. Elisabetha (Harm)

Handrich, K. Margaretha (Scheuermann)

Harm, Edna (Witte)

Harm, Elizabeth

Harm, Emma (Becker)

Harm, Henry / Harm, Johann Michael / Harm, Johann Philipp / Harm, Katherina (Kitsch)

Harm, Michael of Cleveland

Harm, Michael of New Jersey

Harm, Philipp

Häuser, Philipp

Hawer

Heinrich

Herr, Hans Philipp

Hischen. See Hisgen

Hisgen, Susannah Margaretha (Harm)

Hisgen, Gertraud (Hoehn)

Hoffman, Jacob

Höge, Jacob

Hoehn (see Höhn)

Höhn, Adam / Höhn, Frank / Höhn, Gretel / Höhn, Jacob / Höhn, Johannes / Höhn, Matthias / Höhn, Michael

Hoppensack, Henry F. and Maria Illsabein Hissenkemper

Hoppensack, Olga (Gressle)

Hoppensack, W. F.

Hucks, Jacob

Joh. Ehrhard

Kallstadt, village of

Kirchner, Philipp

Krehter

Kröther

Laises

Lebhard

Lederer, Heinrich and Kate

Leises. See Laises

Leycker

Martinger, Hans

Mäurer, Heinrich

Meckenheim, village of

Michel, Anna Maria (Selzer) 43

Michel, Jacob / Michel, Johann / Michel, Reichert

Oberholz

Obersülzen, village of

Ohler, Daniel / Ohler, Jacob

Ohler, Elisabetha Katherina (Handrich)

Parma, Ohio

Pletscher (see also Bleschers)

Rabalier. See Rapparlie, Johann

Räder, Nicholas

Rapparlie, Elizabeth

Rapparlie, Jacob / Rapparlie, Johann / Rapparlie, John / Rapparlie, Wilhelm

Reibold, Anna Elisabetha

Rheingönnheim, town of

Riethaler

Risser

Schäfer, Philipp

Schantz

Scherer, Martin

Scheuermann, George

Scheuermann, John

Schmidt Hannes

Schmidt, Paul

Schuster, Fred and Mary (Crolly)

Schuster, Karl

Schweizer, F. B.

Selzer, Jacob / Selzer, Jean / Selzer, Michael

Siringer, Jacob

Stein

Stenzel, Wilhelm

Steppler, Rev.

Stützel

Umbstädter

Umstader. See Umbstader

Wachenheim, village of

Weisenheim am Sand, village of

Wekerling, George

Wernz

Westfalia

Winter, Ludwig