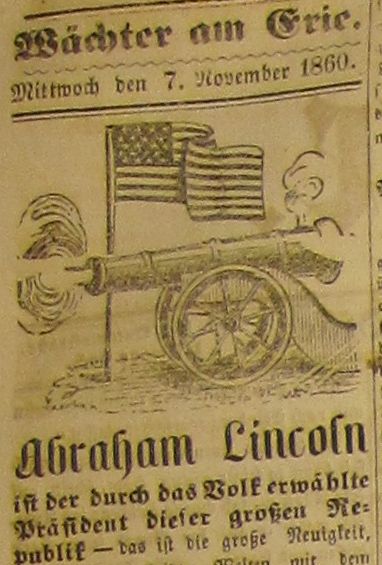

Recently, I saw the movie Lincoln, which shows a time near the end of the Civil War when the deep divide between the North and South is at its most painful and tragic. The movie covers the philosophical and political differences between free and slave states, spending much less time on economic considerations. When the Englishwoman Isabella Bird traveled through Cincinnati, Ohio to Covington, Kentucky in 1854, her foreigner’s account dwells more heavily on what the system of slavery was doing to the Southern economy:

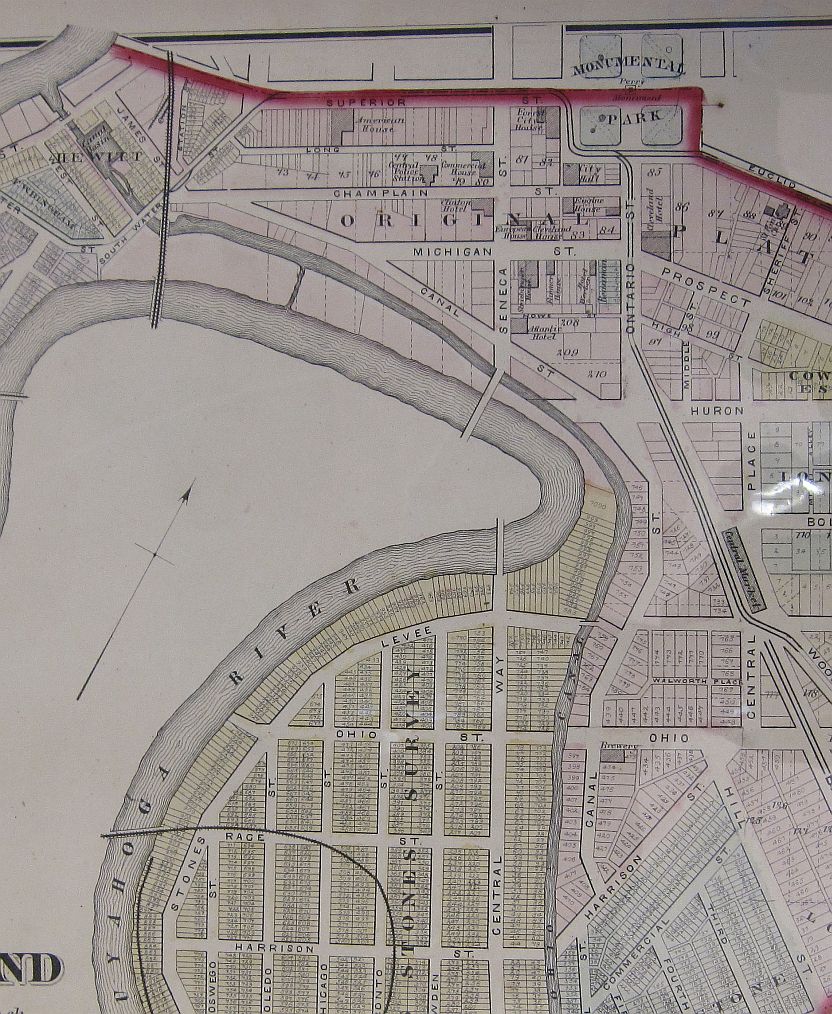

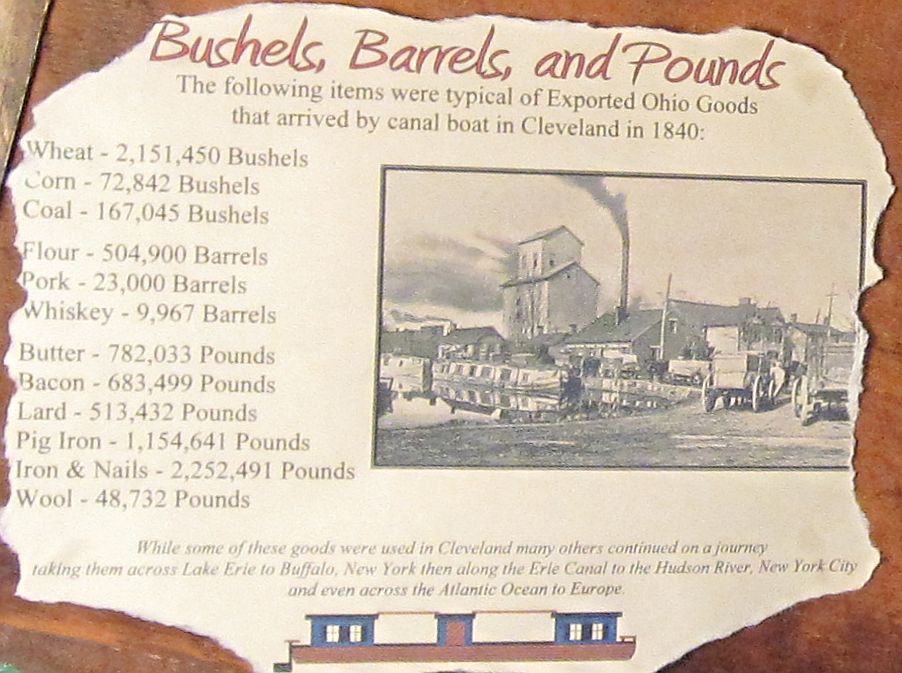

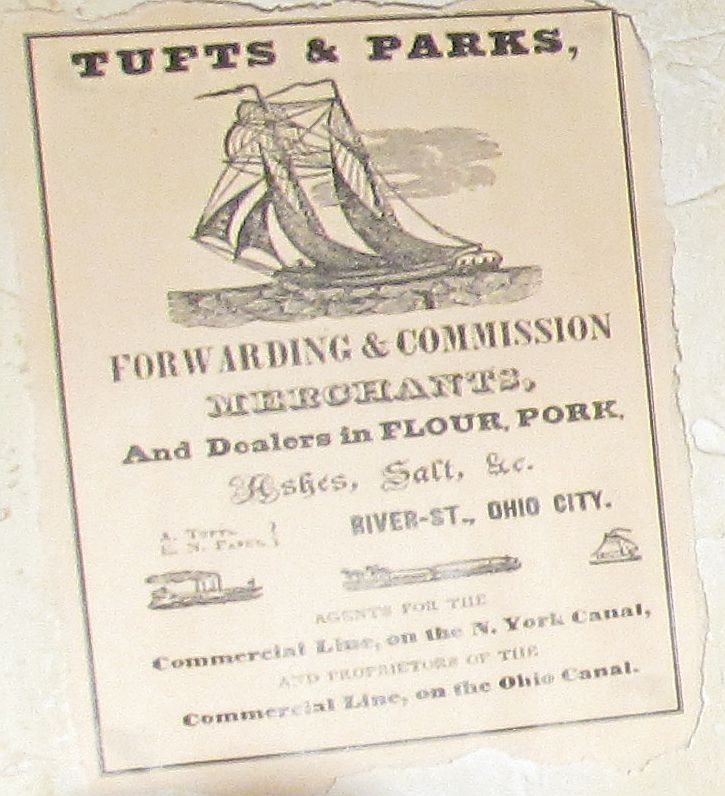

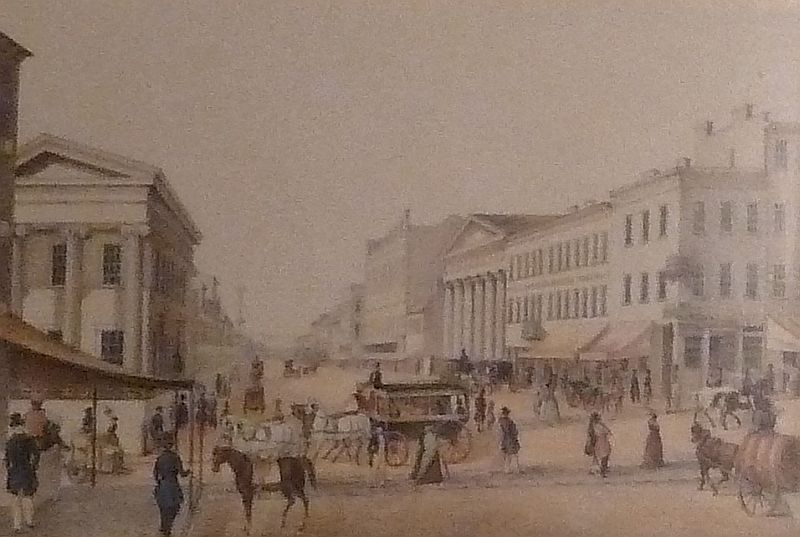

“Cincinnati is the outpost of manufacturing civilization … It has regular freight steamers to New Orleans, St. Louis, and other places on the Missouri and Mississippi; to Wheeling and Pittsburgh, and thence by railway to the great Atlantic cities, Philadelphia and Baltimore, while it is connected with the Canadian lakes by railway and canal to Cleveland. … vast establishments for the production of household goods arrest the attention of the visitor to the Queen City. At the [furniture] factory of Mitchell and Rammelsberg common chairs are the principal manufacture … Rocking-chairs, which are only made in perfection in the States, are fabricated here, also chests of drawers … The workmen at this factory (most of whom are native Americans and Germans, the English and Scotch being rejected on account of their intemperance) earn from 12 to 14 dollars a week. … There are vast boot and shoe factories, which would have shod our whole Crimean army in a week … The manufactories of locks and guns, tools, and carriages, with countless other appliances of civilized life, are on a similarly large scale. … Cincinnati is famous for its public libraries and reading-rooms. The Young Men’s Mercantile Library Association has a very handsome suite of rooms opened as libraries and reading-rooms, the number of books amount to 16,000, with upwards of 100 newspapers. … But after describing the beauty of her streets, her astonishing progress, and the splendour of her shops, I must not close this chapter without stating that the Queen City bears the less elegant name of Porkopolis; … Cincinnati is the city of pigs. … At a particular time of year they arrive by the thousands–brought in droves and steamers to the number of 500,000–to meet their doom. … There are huge slaughter-houses behind the town … the ‘hog crop’ is as much a subject of discussion and speculation as the cotton crop of Alabama, the hop-picking of Kent, or the harvest in England.

“Cincinnati is the outpost of manufacturing civilization … It has regular freight steamers to New Orleans, St. Louis, and other places on the Missouri and Mississippi; to Wheeling and Pittsburgh, and thence by railway to the great Atlantic cities, Philadelphia and Baltimore, while it is connected with the Canadian lakes by railway and canal to Cleveland. … vast establishments for the production of household goods arrest the attention of the visitor to the Queen City. At the [furniture] factory of Mitchell and Rammelsberg common chairs are the principal manufacture … Rocking-chairs, which are only made in perfection in the States, are fabricated here, also chests of drawers … The workmen at this factory (most of whom are native Americans and Germans, the English and Scotch being rejected on account of their intemperance) earn from 12 to 14 dollars a week. … There are vast boot and shoe factories, which would have shod our whole Crimean army in a week … The manufactories of locks and guns, tools, and carriages, with countless other appliances of civilized life, are on a similarly large scale. … Cincinnati is famous for its public libraries and reading-rooms. The Young Men’s Mercantile Library Association has a very handsome suite of rooms opened as libraries and reading-rooms, the number of books amount to 16,000, with upwards of 100 newspapers. … But after describing the beauty of her streets, her astonishing progress, and the splendour of her shops, I must not close this chapter without stating that the Queen City bears the less elegant name of Porkopolis; … Cincinnati is the city of pigs. … At a particular time of year they arrive by the thousands–brought in droves and steamers to the number of 500,000–to meet their doom. … There are huge slaughter-houses behind the town … the ‘hog crop’ is as much a subject of discussion and speculation as the cotton crop of Alabama, the hop-picking of Kent, or the harvest in England.

Kentucky, the land, by reputation, of “red horses, bowie-knives, and gouging,” is only separated from Ohio by the river Ohio; and on a day when the thermometer stood at 103 degrees in the shade I went to the town of Covington. Marked, wide, and almost inestimable, is the difference between the free state of Ohio and the slave-state of Kentucky. They have the same soil, the same climate, and precisely the same natural advantages, yet the total absence of progress, if not the appearance of retrogression and decay, the loungers in the streets, and the peculiar appearance of the slaves, afford a contrast to the bustle on the opposite side of the river, which would strike the most unobservant. I was credibly informed that property of the same real value was worth 300 dollars in Kentucky and 3000 in Ohio! Free emigrants and workmen will not settle in Kentucky, where they would be brought into contact with compulsory slave-labour; thus the development of industry is retarded, and the difference will become more apparent every year, till possibly some great changes will be forced upon the legislature.” –Isabella Bird, My First Travels in North America, pp. 94-98

Indeed. Watching Lincoln in living color, the heart-rending portrayal of how many lost their lives for freedom, I was reminded again that we become complacent about freedom at our peril.