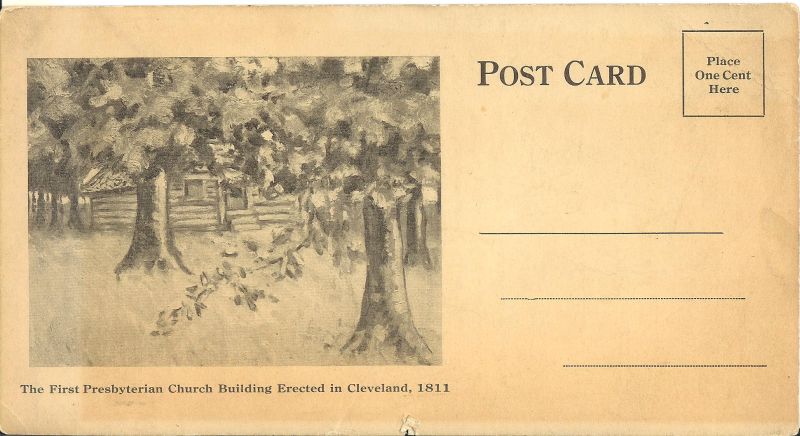

I am very impressed by the Western Reserve Historical Society (WRHS). Unless you’re a history buff, you might not know the term “Western Reserve” refers to the northeastern part of Ohio.

The Wikipedia entry for the Connecticut Western Reserve describes it thus: “the lands between the 41st and 42nd-and-2-minutes parallels that lay west of the Pennsylvania border. Within Ohio the claim was a 120-mile (190 km) wide strip between Lake Erie and a line just south of Youngstown, Akron, New London, and Willard …” The strip of land in Ohio included Cleveland. Hence, names like “Church of the Western Reserve” and “Case Western Reserve University.”

Among the Western Reserve Historical Society’s incredible collections, exhibits, archives and online databases, are the following: local funeral home indexes, Jewish marriage and death notices, biographical sketches, Bible records, Early Families in Cleveland Project, Allen E. Cole African American Collections and more. To see the comprehensive list of databases, click here. To search what’s available in their extensive library catalog, click here.

Among the Western Reserve Historical Society’s incredible collections, exhibits, archives and online databases, are the following: local funeral home indexes, Jewish marriage and death notices, biographical sketches, Bible records, Early Families in Cleveland Project, Allen E. Cole African American Collections and more. To see the comprehensive list of databases, click here. To search what’s available in their extensive library catalog, click here.

Each time I see something like “Bible Records Index” or “Early Families in Cleveland Project” my heart beats a little faster. Maybe I’ll find my ancestors there, I think. So far, nothing much has turned up. Why not? For one thing, they were German, so kept to their German clan. Perhaps their names appear in the German newspapers, hard copies of which are available in the WRHS archives library, but not digitized or inventoried by individual names. For another thing, these first-generation immigrants were working men. Furnace operators, barrelmakers, blacksmiths, machinists. The salt (and grit) of the earth. For instance, my great-great-great uncle Jakob Handrich, who immigrated to Cleveland in 1840, appears rarely (often with alternate spellings, Handrick, Hendricks, Henry). If at all. Here’s what I know.

Jakob Handrich Life Events

*Born circa 1822, presumably in Meckenheim

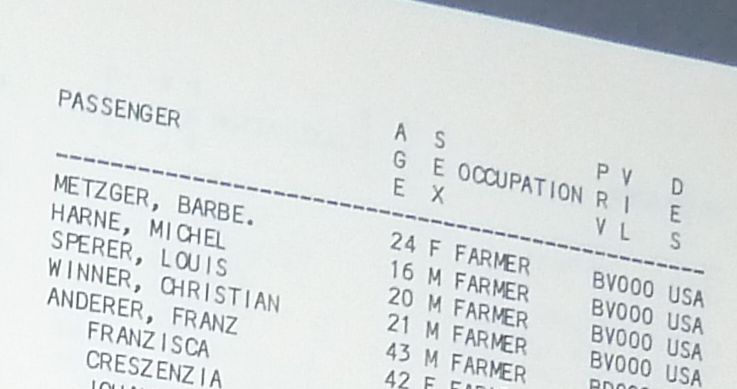

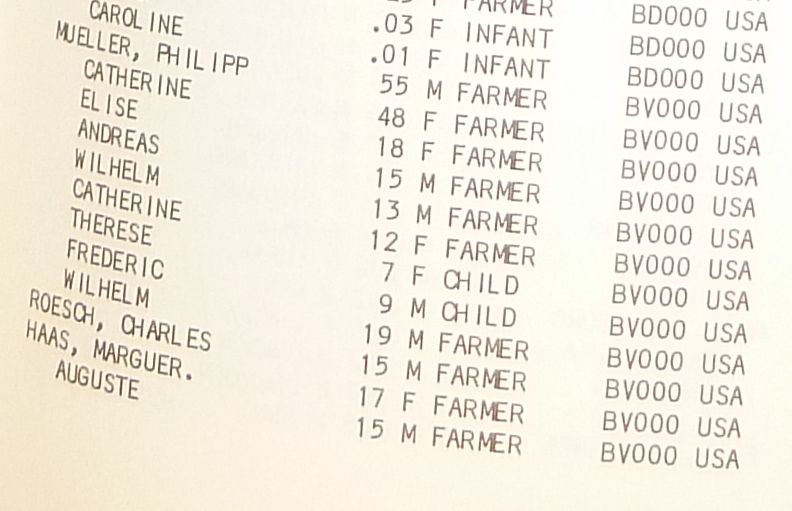

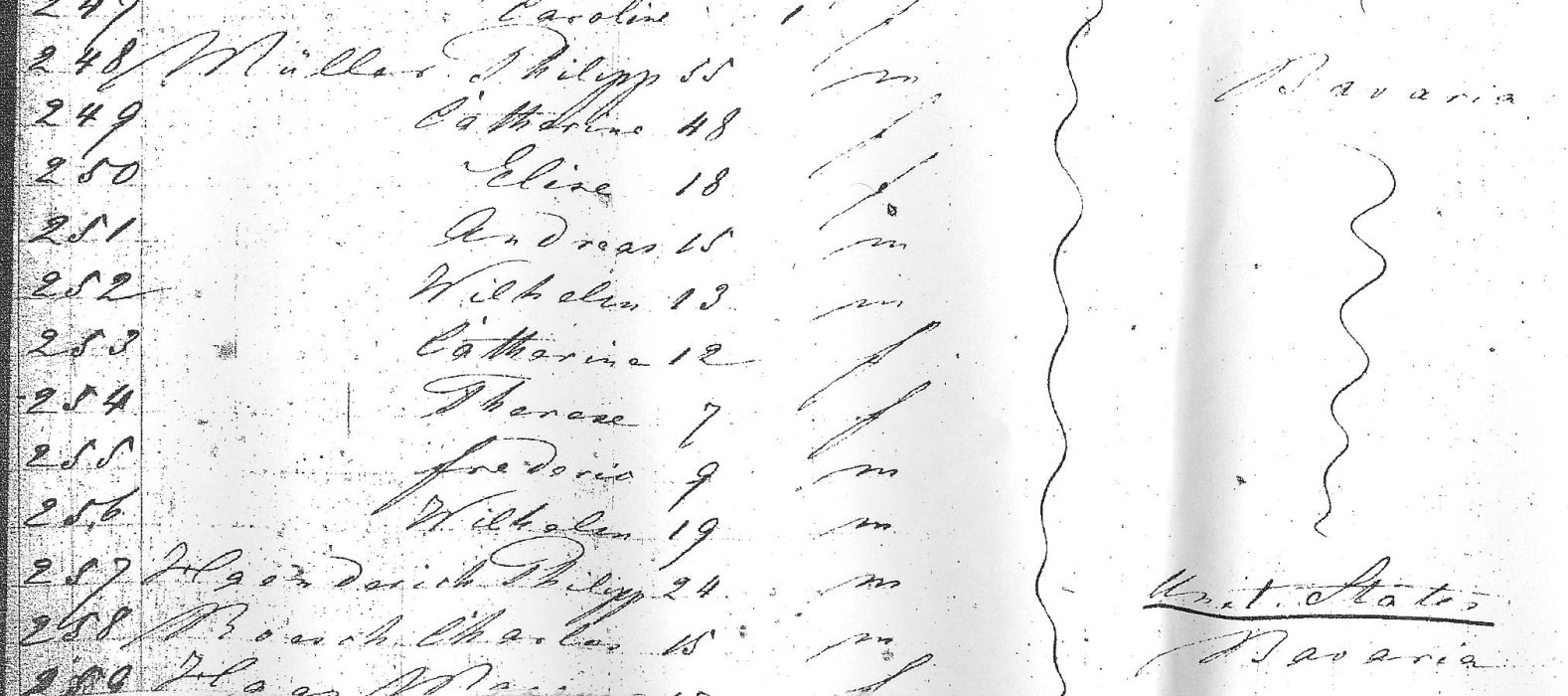

*Arrived July 29, 1840 in New York on Ship Anson, 18 years old, traveling with his parents, 2 older sisters and 1 older brother

*In 1841, Jakob settled in Cleveland, Ohio, trained as a cooper (barrelmaker) and earned $5 per week.

*In 1843, he found work as a blacksmith in a factory “where steaming kettles and machines for steamboats and railways were being built” and earned $1.50/day

*In 1848, he made a journey into the southern states, approximately 2000 miles, including Cincinnati, St. Louis, Mobile and New Orleans

*In 1849, he bought a property ($600 cash) and built a house himself (nicknamed “House Place”) and lived there with his elderly parents until their deaths in the mid-1850s.

*By 1858, Jakob had been swept up in the California Gold Rush and traveled around South America by ship to California. At first, he made a lot of money as a blacksmith in San Francisco, but then the times got bad and he traveled to Sacramento Sutte to dig for gold and try his luck.

*In 1862 he was still in California, and had amassed approx. $12,000 in the bank.

*In 1864, he was in Cincinnati and contemplated returning to California.

*In 1869, he had married, had one son, and lived again in Cleveland.

*In 1870, he went to look for work in Columbus, and traveled between Columbus and Cleveland in subsequent years.

*In 1896 he was laid to rest at Green Lawn Cemetery in Columbus, Ohio.

Little of the above info turns up in genealogy databases; it all comes from several dozen letters in my family’s possession. I have no birth record, marriage record, proof of children. Only his name on a ship manifest, and his gravestone, where his name appears as Jacob Handrick. Maybe that’s not even him, but it’s as close as I can get. Which leads me to believe there have to be thousands and thousands of others like him. Invisible souls. And he was male. Think of the invisible women–early city directories list only the men of the household, women’s names changed when they married, and so on. Without the letters, the fact that Jakob Handrich ever existed would seem a mere mirage.

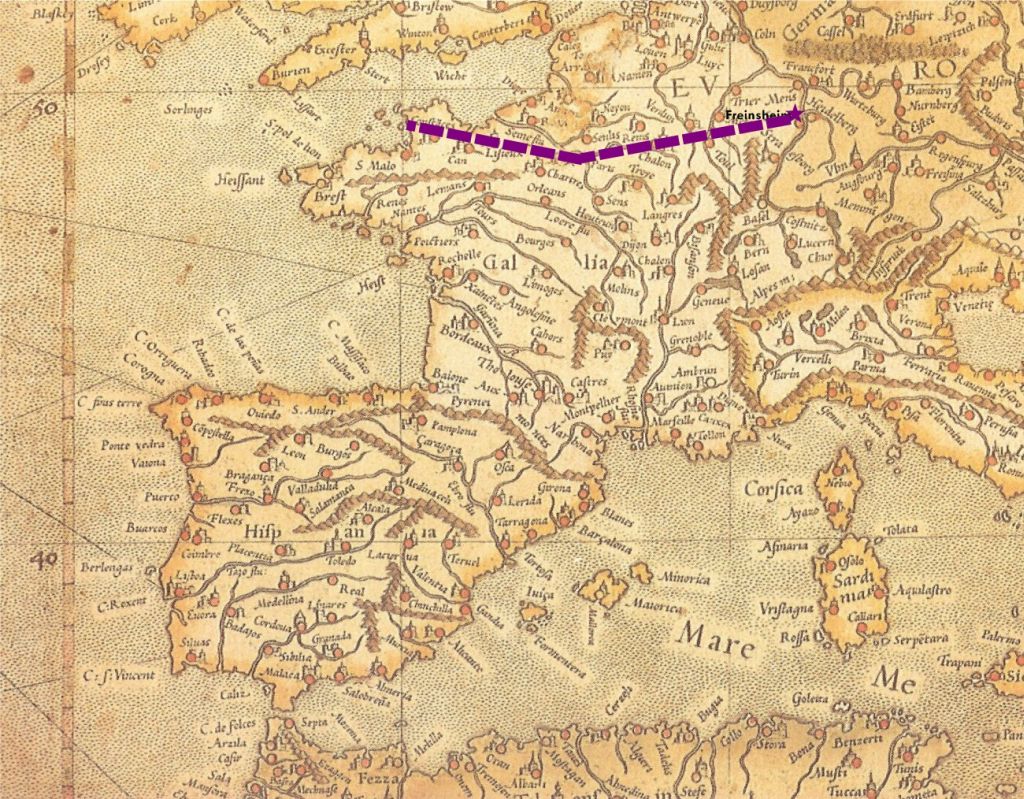

Over the holidays, Dr. Görtz sent me a pdf of a “Survey in table form of emigration to overseas countries from Freinsheim.” He found a copy in the Landesarchiv in Speyer (where one also can visit the 11th century cathedral and History Museum of the Palatinate, both pictured here). So far, I’ve been able to discern the following names: Wiegand, Selzer, Höhn, Schneider, Hoffmann, Kaufmann, Gumbinger, Diehl, Schulz, Amend, Retzer, Depper, Bisgen, Schwab, Bloch, Drescher, Haas, König, Kirchner, Weilbrenner, Weibert, Schalter, Arter, Reichert, Heinz, Schmitt, Först, Fränkel, Aul, Adler, Heim, Hermann, Jacob, Kohl, Köhler, Bawel, Debus, Schaadt. Check it out for yourself: Tabellarische Übersicht der Auswanderungen. The table is not complete (my ancestor Michael Harm, who left at age 15, is not listed), but I include it here for others who might have better luck, both with finding their ancestors and/or deciphering the Alte Deutsche Schrift.

Over the holidays, Dr. Görtz sent me a pdf of a “Survey in table form of emigration to overseas countries from Freinsheim.” He found a copy in the Landesarchiv in Speyer (where one also can visit the 11th century cathedral and History Museum of the Palatinate, both pictured here). So far, I’ve been able to discern the following names: Wiegand, Selzer, Höhn, Schneider, Hoffmann, Kaufmann, Gumbinger, Diehl, Schulz, Amend, Retzer, Depper, Bisgen, Schwab, Bloch, Drescher, Haas, König, Kirchner, Weilbrenner, Weibert, Schalter, Arter, Reichert, Heinz, Schmitt, Först, Fränkel, Aul, Adler, Heim, Hermann, Jacob, Kohl, Köhler, Bawel, Debus, Schaadt. Check it out for yourself: Tabellarische Übersicht der Auswanderungen. The table is not complete (my ancestor Michael Harm, who left at age 15, is not listed), but I include it here for others who might have better luck, both with finding their ancestors and/or deciphering the Alte Deutsche Schrift.