In researching about my blacksmith great-great-grandfather, I’ve often turned to a book called Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. by Ron Chernow.

John D. Rockefeller (born 1839) was a contemporary of Michael Harm (born 1841), and both men migrated in the mid-19th century to Cleveland to build their fortunes (Rockefeller’s fortune was more substantial and enduring, but still).

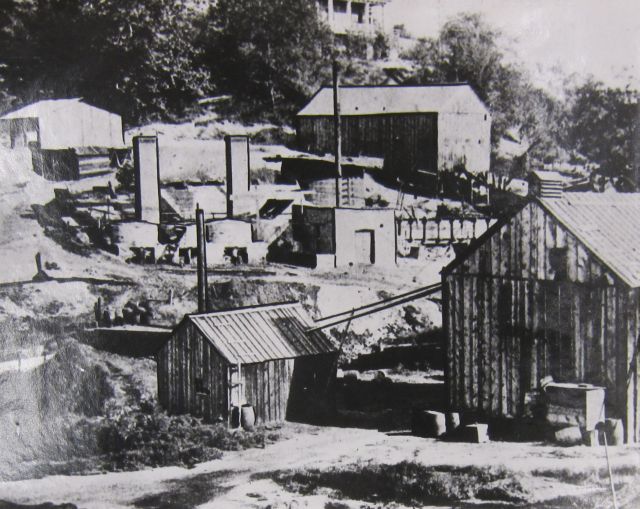

Rockefeller set up his first oil refineries, the Excelsior Works, Chernow writes, “on the red-clay banks of a narrow waterway called Kingsbury Run.” In this tidbit, I find two startling coincidences. One, Michael Harm spent his three-year apprenticeship in Cleveland at a wagon shop situated quite near Kingsbury Run. And two, before the refineries cropped up in Kingsbury Run, another ancestor, my great-great-grandfather H.F. Hoppensack, operated his brickworks there. In the obituary of Henry F. Hoppensack, it states: “From 1848- 1851, Mr. Hoppensack manufactured brick on Broadway Hill where the Standard Oil Co. is now located.”Here’s another coincidence–Harm & Schuster made business wagons for the Chandler & Rudd grocery. In Chernow’s account of Rockefeller’s life, he states: “[Rockefeller’s] younger sister, Mary Ann, married a genial man named William Rudd, the president of Chandler and Rudd, a Cleveland grocery concern.”

Although John D. Rockefeller and Michael Harm were about the same age and lived and worked in Cleveland during the same era, I doubt they knew one another on a first-name basis. The English, German and Irish enclaves in Cleveland in the mid-19th century did not fraternize so often. Nonetheless, it’s a six-degrees-of-separation kind of thing. In The Titans, Chernow describes those early days of oil that I am certain had a profound impact on my great-great-grandfather, and all Clevelanders, as well.

“At the time [just following the Civil War], refiners were tormented by fears that the vapors might catch fire, sparking an uncontrollable conflagration. … Mark Hanna, who later managed President McKinley’s campaign, recalled how one morning in 1867 he woke up and discovered that his Cleveland refinery had burned to the ground, wiping out his investment …’I was always ready, night and day, for a fire alarm from the direction of our works,’ said Rockefeller. ‘Then proceeded a dark cloud of smoke from the area, and then we dashed madly to the scene of the action. So we kept ourselves like the firemen, with their horses and hose carts always ready for immediate action.’

“… In those years, oil tanks weren’t hemmed in earthen banks as they later were, so if a fire started it quickly engulfed all neighboring tanks in a flaming inferno. Before the automobile, nobody knew what to do with the light fraction of crude oil known as gasoline, and many refiners, under cover of dark, let this waste product run into the river. ‘We used to burn it for fuel in distilling the oil,’ said Rockefeller, ‘and thousands and hundreds of thousands of barrels of it floated down the creeks and rivers, and the ground was saturated with it, in the constant effort to get rid of it.’ The noxious runoff made the Cuyahoga River so flammable that if steamboat captains shoveled glowing coals overboard, the water erupted in flames.”

Randy Newman’s “Burn On” may have been about the Cuyahoga River fire in 1969, but apparently, that river had already burned one hundred years ago.