The Tenement Museum visitor center and shop at 103 Orchard Street, New York, New York has a great selection of books. I got caught up in such titles as:

When Did the Statue of Liberty Turn Green?: And 101 Other Questions About New York City, until a title caught my eye a few shelves over: The German-American Experience, by Don Heinrich Tolzmann. A must-buy. When I brought it to the counter, the salesperson sighed.

“You found one of two books we carry here about German Americans. I wish we had more.”

I should have asked her what the other title was, but my tour of 97 Orchard Street was about to begin. Back home, when I visited the Tenement shop on-line, I saw what the sales clerk meant. In addition to books about New York, the shop inventory listed books “Of Irish Interest,” “Of Jewish Interest,” and “Of Italian Interest.” Nothing “Of German Interest.” Humph. Maybe I bought the last one.

Tolzmann’s The German-American Experience is well researched. I love how it includes a write-up of Charles Sealsfield (a pen name–his real name was Karl Postl), whose books were as influential as James Fenimore Cooper’s “Leather-stocking Tales” series in giving 19th-century Germans an idealized vision of America.

Tolzmann also briefly mentions “The Hambacher Fest and the Thirtyers,” something I rarely come across in English versions of German history. The 1832 Hambacher Fest is where the black, red and gold tricolor was first flown as a symbol of democratic rebellion.

Tolzmann also briefly mentions “The Hambacher Fest and the Thirtyers,” something I rarely come across in English versions of German history. The 1832 Hambacher Fest is where the black, red and gold tricolor was first flown as a symbol of democratic rebellion.

From May 27-30, 1832, tens of thousands of craftsmen, students, farmers, officials, and young intellectuals gathered at the ruins of the castle of Hambach to listen to speeches on liberty, reform, and the tyranny of the German princes. Like the Wartburg Fest of 1817, the Hambacher Fest culminated in arrests, dismissals of professors from their positions, espionage, censorship, and police surveillance. These oppressive measures caused many to emigrate to America. (The German-American Experience, p. 166)

Hambach Castle, situated in the foothills of the Haardt Mountains near Neustadt, is now a museum. I found the interpretive displays there very informative. Here are just a few personalities of the day:

Friedrich Deidesheimer

The merchant and vineyard owner Friedrich Deidesheimer, of Neustadt an der Haardt, was a member of the Civil Guard, and in 1832 was a signatory to the invitation to the Hambach Festival. On May 27, Deidesheimer delivered a speech calling for a guarantee of civil rights and liberties by the prince and concluded with an appeal: “Long live freedom / Long live the order.”

Daniel Friedrich Ludwig Pistor

Daniel Friedrich Ludwig Pistor, of Bergzabern, studied law in Munich, receiving his doctorate in 1831. The political climate in Bavaria had intensified under King Ludwig I. At the Hambach Festival, Pistor gave a speech so revolutionary that he had to flee to France to avoid arrest. In absentia, he was sentenced to one year in prison. His radical writings in Paris earned him another indictment and conviction for treason. Living as an exile, Pistor joined the “covenant of the outlaws,” a circle of emigres. A clemency request was rejected by King Ludwig I.

Following the 1832 Hambacher Fest, which drew protesters from all over Europe, a June rebellion in Paris also failed. You may have heard something more about that French uprising than you realize. Does Les Miserables sound familiar?

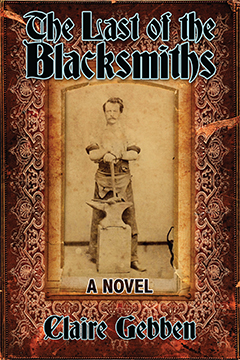

My book is out in stores and online. Reviews are starting to come in on GoodReads, at Morganti Writes and on Amazon.

My book is out in stores and online. Reviews are starting to come in on GoodReads, at Morganti Writes and on Amazon.