It’s both exciting, and nerve-wracking, to head out on an exploration without a plan. But I’ve found in the Highlands, and for that matter in book research in general, planning for the unplanned is an excellent way to go. While traveling in the Highlands, experience has taught me the true mettle of the people’s character tends to be veiled, as if hidden behind wispy, low-lying clouds. To find it, you have to enter the mist. Just as in book research, you don’t know what you’re looking for until you find it.

After my adventure exploring the valleys and byways of the River Nairn (see previous post), the following day, I hoped to make a journey along the River Findhorn (since several characters in the novel I’m researching came from parishes there). I first browsed the internet for local historic sites and museums, but turned up frustratingly little (just the usual castles and forts, not the stuff of my novel). As I got in the car on a dripping gray morning, I hesitated turning on the ignition. I could just skip it, I even thought. The gray weather made for a perfect opportunity for holing up with a good book, not for gallivanting across the countryside on verge-less roads (road shoulders in Scotland are called “verges,” which, from what I can tell, are non-existent). I checked the map one last time for Route A940, which follows the River Findhorn, then added a mental note to keep to the left side of the road at all times, then fired up the engine.

As I drove along, wincing every time a large bus or truck whooshed past within a hair’s-breadth of my little economy car, I noticed a sign for Logie Steading. Steading? It wasn’t a brown sign, like most tourist signs are in the Highlands, but offered shops and gardens and seemed open to the public, and said something about Findhorn Riverwalks, so I turned down the little lane. At the car park, I spotted Logie’s Whisky and Wine shop, and headed over to see about some samples to take home with me. Hence, encountered the Whisky Wall (the proprietor’s term for it, not mine. He invited me to take a picture).

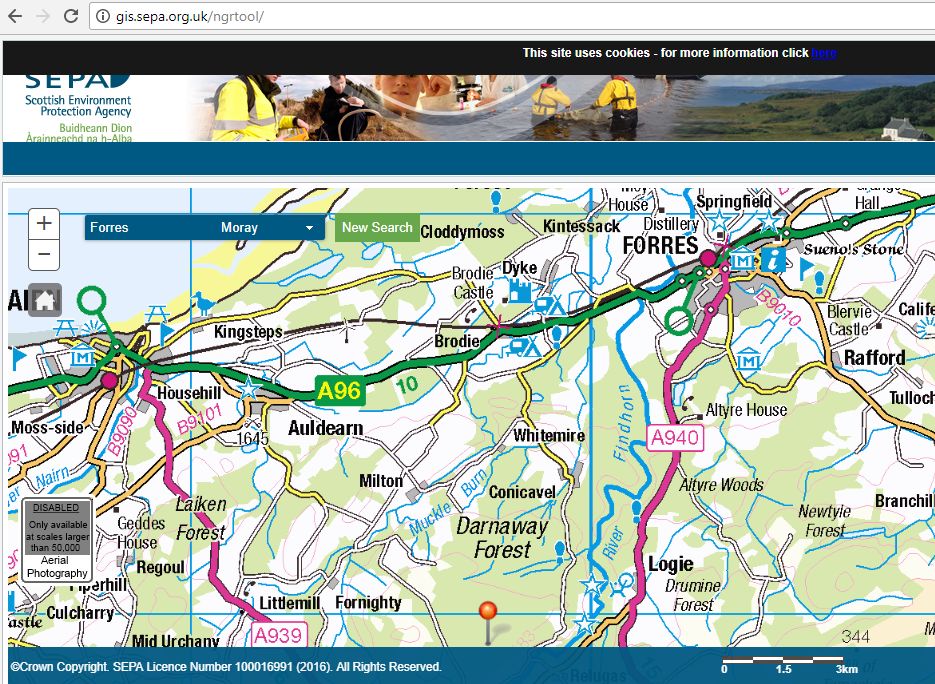

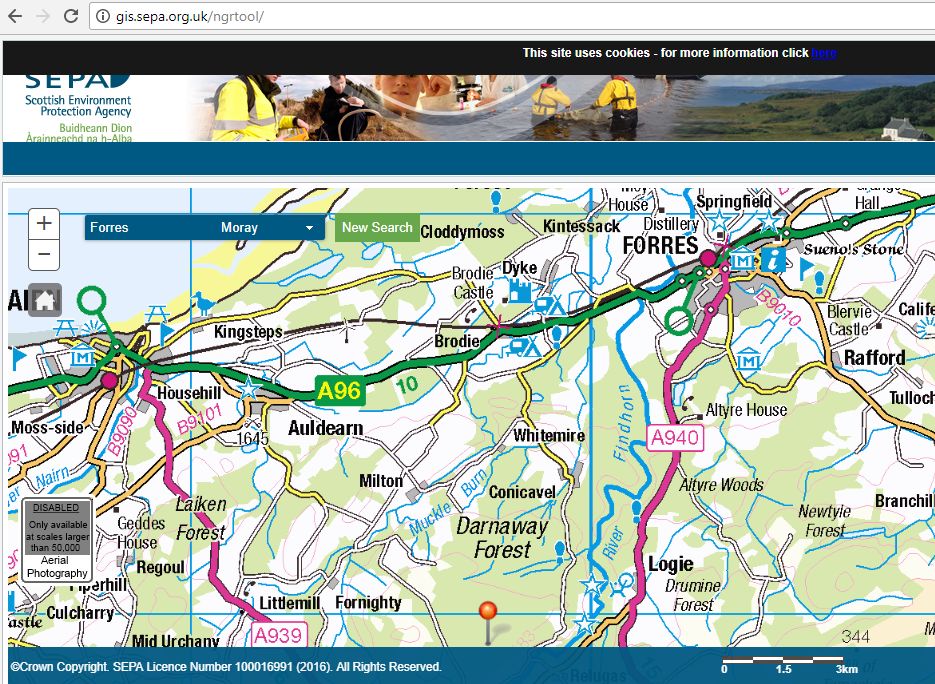

No doubt, at this point you’re thinking: Wait, weren’t you there to research? Well, yes I was. I was also trying to keep my wits about me for driving, so I did not partake of the offered samples. (I did pick up several airplane-sized bottles to take home, naturally.) It being quite early, no one else was in the shop, so I spoke at length with the proprietor, who showed me something that would have been invaluable had I known about it from the get-go. A Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) map that gives you layers upon layers of maps — from roads to bike trails to hiking trails to topography. Double-click, and you can go in layer after layer to see the terrain, wherever you are, whatever you need to know. Amazingly helpful.

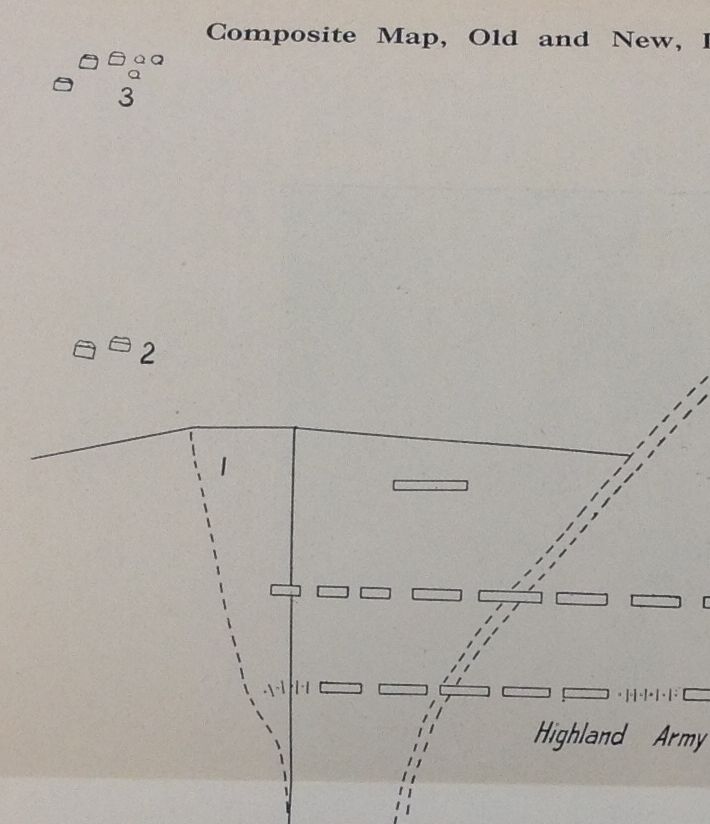

As you can see from the above, so far, I’d driven from Forres down the red route to Logie. It turned out the Logie Steading was started by Sir Alexander Grant, a baker who made his riches by inventing the, wait for it, digestive biscuit. It’s now the River Findhorn Heritage Centre, and has a terrific museum about the local people and customs throughout history. There was even a map on the wall outlining just the places I needed to visit.

First stop, Randolph’s Leap (in the Highlander’s typical flair for obfuscation, Randolph didn’t leap it, Alistair did).

The River Findhorn is especially turbulent and angry right now due to a summer of constant rain.

Next stop, Ardclach Kirk, just on the banks of the River Findhorn. Parishioners lived on both sides of the river. As there was no bridge, they had to travel across by boat, which led to several drownings.

The kirk was so low in the valley the bell could not be heard, so the enterprising Presbyterians built a belltower up above the cliff to sound the call to services, for funerals and so on.

The ochre color of the belltower may seem odd, but is actually the color of paint used in the era the tower was built, circa 1655.

Finally, I leave you with just one example of details in the Logie museum that are of use to the historical novelist. The drawing of a woman’s bonnet, with thorough description.

This woman’s bonnet is called a “mutch.”

Mutches varied from very fine ones with insets of lace, or an occasional coloured ribbon, to simple ones for everyday use or as nightcaps. … Many women had a special box in which they would carry a fresh mutch which they would put on just before reaching the church or the friends they might be visiting.

Before the mutch, women often wore the “toy,” described as “two long broad stripes of linen attached to a cap fitted closely to the head.” It makes me wonder, is this where the expression: “don’t toy with me,” comes from?

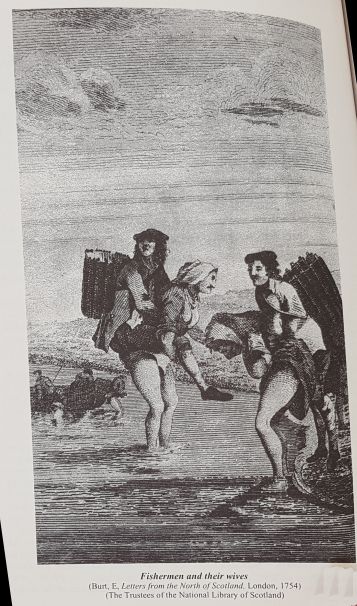

Tinsmiths of the day were also known as tinkers, handy at most repairs. Upon further research, I turned up this book: Last of the Tinsmiths: The Life of Willie MacPhee by Sheila Douglas. In a nutshell:

Tinsmiths of the day were also known as tinkers, handy at most repairs. Upon further research, I turned up this book: Last of the Tinsmiths: The Life of Willie MacPhee by Sheila Douglas. In a nutshell: