Today I am in Bremen, where I am supposed to be. It’s something of a miracle. When navigating the train system in Germany, it helps to have someone along to negotiate all the details. Friday when I set off on my journey to Berlin, I had three Golden Tickets (of the Willy Wonka variety, negotiated by Angela) in my travel bag. All correct. All ordered early to save Euros. Angela saw me to the first train and waved good-bye from the platform.

Today I am in Bremen, where I am supposed to be. It’s something of a miracle. When navigating the train system in Germany, it helps to have someone along to negotiate all the details. Friday when I set off on my journey to Berlin, I had three Golden Tickets (of the Willy Wonka variety, negotiated by Angela) in my travel bag. All correct. All ordered early to save Euros. Angela saw me to the first train and waved good-bye from the platform.

I changed trains in Kassel. I went to the correct platform, where the train for Hannover had just departed. I stood on the correct side. I even understood the word verspatung on the PA system, that my train to Berlin would arrive five minutes late. The silly metro people hadn’t bothered to change the Hannover sign yet, but no matter. I knew what was going on. I boarded the train when it pulled into the station. I stood at the entrance to a compartment trying to get the door to open when I spied a little red digital sign that said Hannover. I spun around to the line of people trapped behind me in the narrow hallway.

I changed trains in Kassel. I went to the correct platform, where the train for Hannover had just departed. I stood on the correct side. I even understood the word verspatung on the PA system, that my train to Berlin would arrive five minutes late. The silly metro people hadn’t bothered to change the Hannover sign yet, but no matter. I knew what was going on. I boarded the train when it pulled into the station. I stood at the entrance to a compartment trying to get the door to open when I spied a little red digital sign that said Hannover. I spun around to the line of people trapped behind me in the narrow hallway.

“Nicht Berlin?”

“HANNOVER!” the traveler behind me ennunciated. I barrelled back down the hall “Bitte! Bitte!” (You’re welcome! You’re welcome!) and out of the train just as the doors slipped into locked position.

So Sunday, now a seasoned pro, I am brought by Wolf to the train for Bremen. He sees me off on the platform. It’s an ICE train, the fast, sleek kind. The seats are luxurious leather, molded like those Eames lounge chairs. Wolf waves to me through the window as the train gets underway.

So Sunday, now a seasoned pro, I am brought by Wolf to the train for Bremen. He sees me off on the platform. It’s an ICE train, the fast, sleek kind. The seats are luxurious leather, molded like those Eames lounge chairs. Wolf waves to me through the window as the train gets underway.

Moments later, a man is hovering over me with his ticket in his hand. “Reserviert?” He asks. I blink at him owlishly. He tries again. “Reserviert?” I shrug and produce my ticket. He rolls his eyes and points out his ticket shows a reservation for my seat.

“Then where do I sit?” He shrugs. I bundle my belongings and move to the empty seat in a group of four across the aisle. Five minutes later, same thing. The man across from me also gets booted. I ask a ticket agent where to go. She stares at my ticket and says in English: “You don’t have a reservation.” She waves me to the front of the train. I walk and walk and walk. These trains are long, all seats full. Between train cars by the exits, people sit on the floor.

Eventually, I come to a closed bar area. Two women are sitting at bar tables. One is vacant. I opt for the third table rather than sitting on the floor between cars. It’s a long hour, balancing on the seat, literally a bar running along the window. As the train slows for the station, I continue to the door, and discover a compartment with regular seats, obviously intended for those who didn’t make a reservation.

Eventually, I come to a closed bar area. Two women are sitting at bar tables. One is vacant. I opt for the third table rather than sitting on the floor between cars. It’s a long hour, balancing on the seat, literally a bar running along the window. As the train slows for the station, I continue to the door, and discover a compartment with regular seats, obviously intended for those who didn’t make a reservation.

I’ve landed back in Freinsheim, where my nitty gritty research begins. I am so privileged to have several appointments with local historians. My first visit is with Herr Walter, former pastor of the Freinsheim Protestant Church, and author of a book on Freinsheim history.

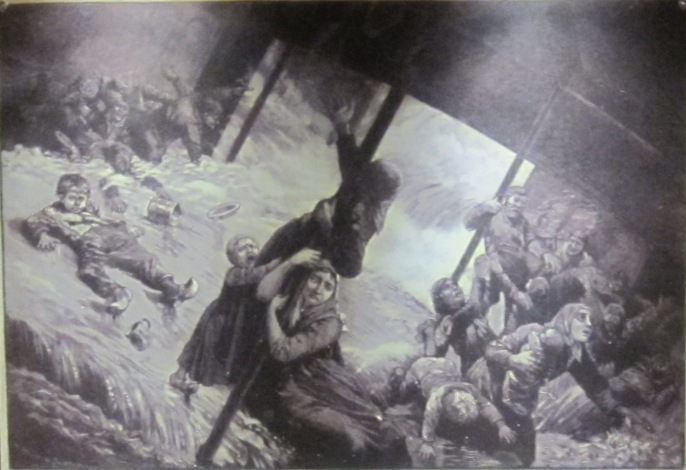

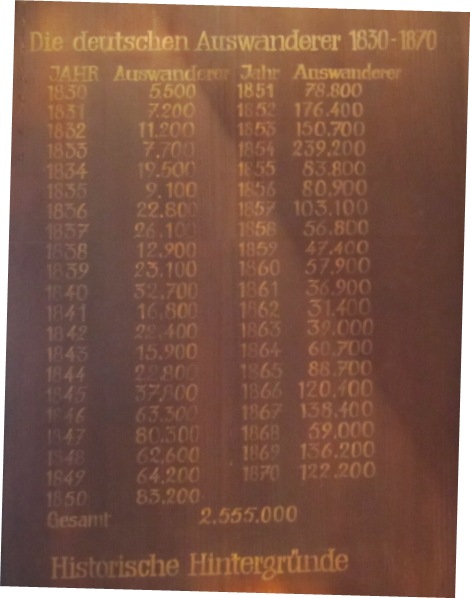

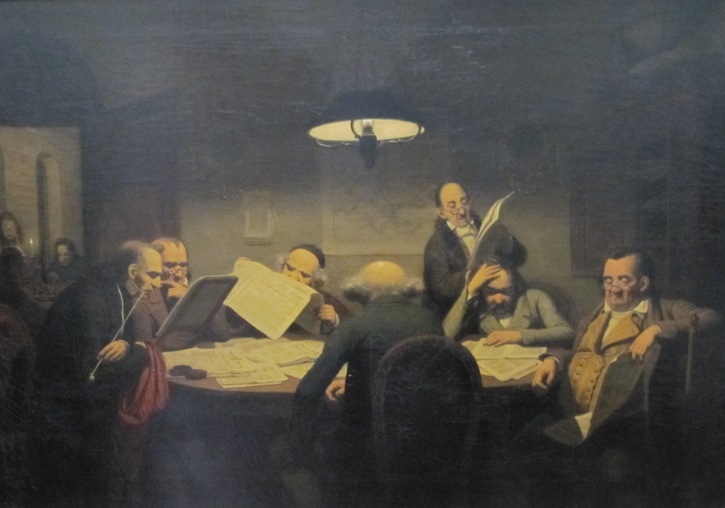

I’ve landed back in Freinsheim, where my nitty gritty research begins. I am so privileged to have several appointments with local historians. My first visit is with Herr Walter, former pastor of the Freinsheim Protestant Church, and author of a book on Freinsheim history. How little I knew before I arrived. Herr Walter has many stories to tell, about a tangle of religion and politics, about revolutions and beheadings, about poverty and exile.

How little I knew before I arrived. Herr Walter has many stories to tell, about a tangle of religion and politics, about revolutions and beheadings, about poverty and exile.

In the afternoon, I walk past the town gate to explore an orchard along the road to Weisenheim am Sand. In my session with Herr Walter, we have leapt through the centuries, but out in these fields, time seems to stand still. I find a snail that is new to me. Cars pass by on road,

In the afternoon, I walk past the town gate to explore an orchard along the road to Weisenheim am Sand. In my session with Herr Walter, we have leapt through the centuries, but out in these fields, time seems to stand still. I find a snail that is new to me. Cars pass by on road,  and every so often the local train, but I also hear farmland sounds: the whinny of horses, farmers joking somewhere among the fruit trees, bird calls and crickets. My happiest find is two ancient willow trees growing together like an old couple still in love.

and every so often the local train, but I also hear farmland sounds: the whinny of horses, farmers joking somewhere among the fruit trees, bird calls and crickets. My happiest find is two ancient willow trees growing together like an old couple still in love.