It’s time for my big visit, the one I’ve been waiting for, a trip to Bremerhaven on the North Sea, to the Deutsches Auswandererhaus (German Emigration Museum). I came across it early via research on my thesis, and I’ve wanted to visit ever since.

It’s time for my big visit, the one I’ve been waiting for, a trip to Bremerhaven on the North Sea, to the Deutsches Auswandererhaus (German Emigration Museum). I came across it early via research on my thesis, and I’ve wanted to visit ever since.

Angela sets me up with a friend in Bremen — Doro –who lets me use her office apartment (and Apple Computer). From Bremen I take the train to Bremerhaven, a port city and emigration center. From here Europeans left daily for centuries, headed for North America, South America, Australia — points all over the globe.

Angela sets me up with a friend in Bremen — Doro –who lets me use her office apartment (and Apple Computer). From Bremen I take the train to Bremerhaven, a port city and emigration center. From here Europeans left daily for centuries, headed for North America, South America, Australia — points all over the globe.

Records show that Michael Harm emigrated from Le Havre, France. But as I walk from the bus to the harbor, I’m loving it already. A three-masted packet ship similar to the Helvetia (the ship of Michael Harm’s voyage in 1857), is docked along the pier.

Records show that Michael Harm emigrated from Le Havre, France. But as I walk from the bus to the harbor, I’m loving it already. A three-masted packet ship similar to the Helvetia (the ship of Michael Harm’s voyage in 1857), is docked along the pier.

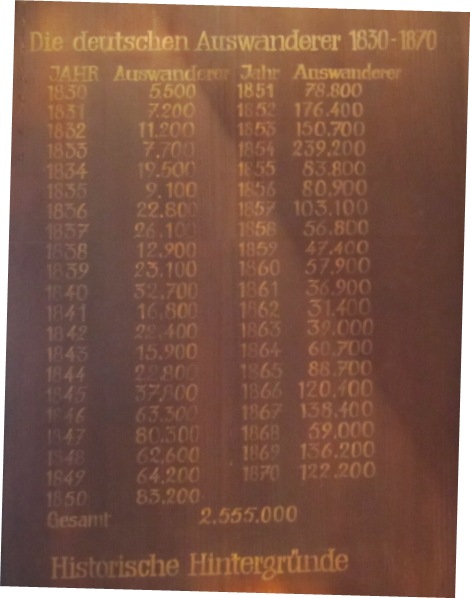

In the Auswandererhaus, there is so much to take in I spend most of the day. I linger over the succinct, to-the-point summaries of different periods of history and reasons people chose to make such a difficult journey,

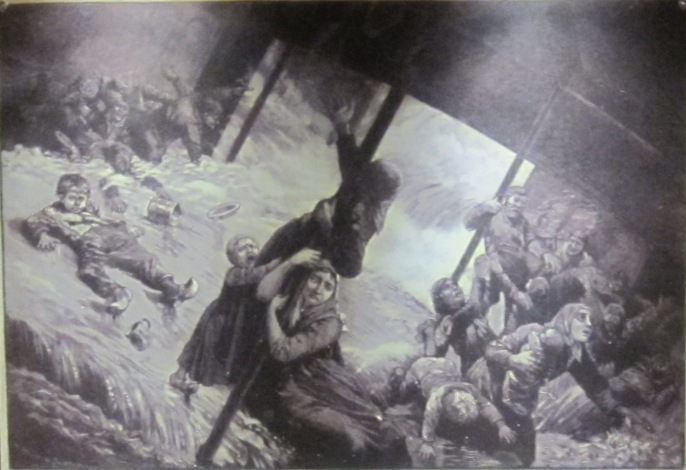

In the Auswandererhaus, there is so much to take in I spend most of the day. I linger over the succinct, to-the-point summaries of different periods of history and reasons people chose to make such a difficult journey,  and spend a long time in the living history exhibit of steerage class accommodations on a mid-19th century ship.

and spend a long time in the living history exhibit of steerage class accommodations on a mid-19th century ship.

At the end of the exhibit, I am reminded Michael Harm did ship out of this port, not the first time he traveled from Germany in 1857, but the last, in 1893. Via the computer at the end, I find both his name and his friend Michael Hoehn’s name on a passenger list of the steamship Columbia.

At the end of the exhibit, I am reminded Michael Harm did ship out of this port, not the first time he traveled from Germany in 1857, but the last, in 1893. Via the computer at the end, I find both his name and his friend Michael Hoehn’s name on a passenger list of the steamship Columbia.