I wonder what the percentage of U.S. Citizens claiming German heritage will be for the 2010 census. On the 1980 census, it was 26.1 percent — one in four citizens. According to a 1983 Report on German Americans, 5.5 million Germans immigrated to the U.S. between 1816 to 1914, because of economics, of drought, political ideologies and differences, because of religious persecution, and on and on. So many of our stories are lost.

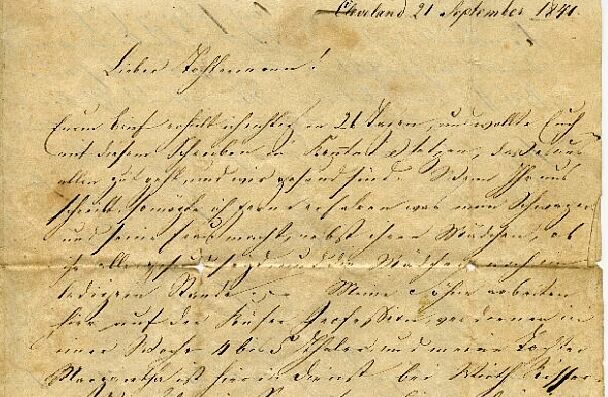

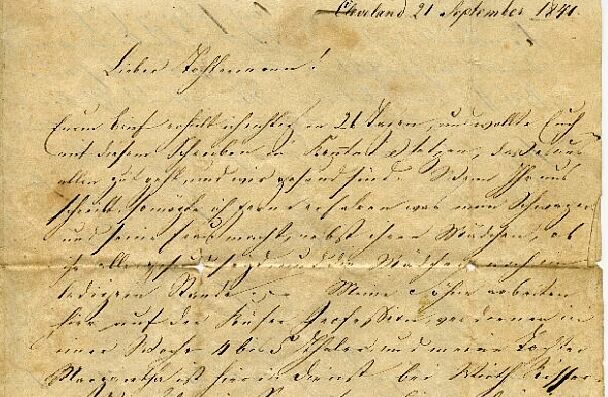

It is rare to have primary source material, such as letters from the time period, and even then, the translation marches along a torturous path. Here is the oldest letter in our possession, written by my greatgreatgreatgreatgrandfather Philipp Heinrich Handrich, shortly after his arrival in Cleveland in 1840.

Lieber Tochtermann!

Lieber Tochtermann!

Euren Brief erhielt ich richtig in 26 Tagen, nun (?) wollte ich Euch mit diesem Schreiben in Kenntnis setzen, dass es uns allen gut geht, und wir gesund sind. Sodann Ihr uns schriebet, so mögte ich ___________ erfahren was mein Schwager und seine Frau macht, nebst ihren Mädchen, ob ihr alle gesund seyd, und die Mädchen machen ledige Stande (?). Meine Söhne arbeiten hier auf der Küfer Grofe (Profe?) und verdienen in einer Woche bis 5 Thaler und meine Tochter Margaretha ist hier in Dienst bei Wirth Biffer (Stiffer?). Wir haben im Sinn für (mehr) noch einige Zeit hier zu bleiben da wir zu etwas besserm noch keine Ausicht haben um Güter zu kaufen wollen wir uns noch nicht umsehen und wenigsten noch ein Jahr lang warten.

**********

Hence, from letters written in faded ink on crumbling paper in old Gothic German, my cousin translates the text (what’s legible, that is) into modern German. Then, English:

************

Dear daughter’s husband („daughterman“)!

Your letter did I receive rightly in 26 days, now (?) I intended to let you know through this letter that we are all well, and we are healthy. Then you wrote to us, so I should_____________ learn what my brother-in-law and his wife are doing, next to their girls, if you are all healthy, and the girls (make?) unmarried state. My sons are working here on the cellarmen (cooper) (profession) and earn within one week 5 Thaler and my daughter Margaretha is here in service at innkeeper Biffer’s (Stiffer?). We have in mind to stay here (more) still some time as we don’t have perspective on something better to buy land we still want to look around and wait at least one more year.

***********

It makes me very happy, therefore, to have secondary source material visiting at the moment — German descendants of the brother of my great-great grandfather. My relative lives in the town of Michael Harm, the town of Freinsheim, Germany. Secondary sources rock!