It may be the ancient mountain forests, or the gray mists that sometimes hang low against the hills, but Germany is home to some fantastic fairy tales. In Marburg, where the Grimm Brothers studied at the University, there are plaques placed around town.

It may be the ancient mountain forests, or the gray mists that sometimes hang low against the hills, but Germany is home to some fantastic fairy tales. In Marburg, where the Grimm Brothers studied at the University, there are plaques placed around town.

They published their collection of Children’s and Household Tales in 1812.

They published their collection of Children’s and Household Tales in 1812.

It is Angela’s youngest daughter Luzi, age 5, who clues me in to the potato sack trick for catching elwedritsches. I was explaining to her grandmother Barbel my moment of angst in the Wasgau forest by the Berwartstein Castle. Matthias and Dave and I had taken the wrong trail to a castle ruin. As we trudged along in the deep woods looking for the right path, Matthias began to warn of a potential hazard.

“If we are still out here in the evening,” he had said, “we must watch out for, what is the word? an animal, yes, an animal, I think, that bites on the skin and sucks the blood and becomes 5 or 6 times its normal size.”

“If we are still out here in the evening,” he had said, “we must watch out for, what is the word? an animal, yes, an animal, I think, that bites on the skin and sucks the blood and becomes 5 or 6 times its normal size.”

Vampire bats came to mind. Transylvania. I made a pretense of calm. “What is it, exactly,” I asked. “An insect, possibly? Or a spider?”

“Okay, right, I think maybe it is a spider.”

A short time later we found the trail and escaped before the curse of the bloodsucking spider. But Matthias’ description stayed with me. Was this real, or was Matthias pulling my leg?

So Luzi, Barbel and I are sitting around the table and I ask: “Is there an animal that bites on the skin and sucks blood and grows to 5 or 6 times its size?”

So Luzi, Barbel and I are sitting around the table and I ask: “Is there an animal that bites on the skin and sucks blood and grows to 5 or 6 times its size?”

Frowns and much discussion ensue. She has to stop to explain to Luzi what I am asking. “I think Matthias was telling you a Fabel,” she says, laughing. Luzi wants to know what a Fabel (fable) is. Barbel answers Luzi, and suggests the creature might have been a Zecke. I leaf through the dictionary and there it is, so obvious. A Zecke is a tick.

But now Barbel and Luzi are going on about Fabels, about elwedritsches in the Palatinate. Apparently they are shy, and won’t come out unless you trick them into it.

But now Barbel and Luzi are going on about Fabels, about elwedritsches in the Palatinate. Apparently they are shy, and won’t come out unless you trick them into it.

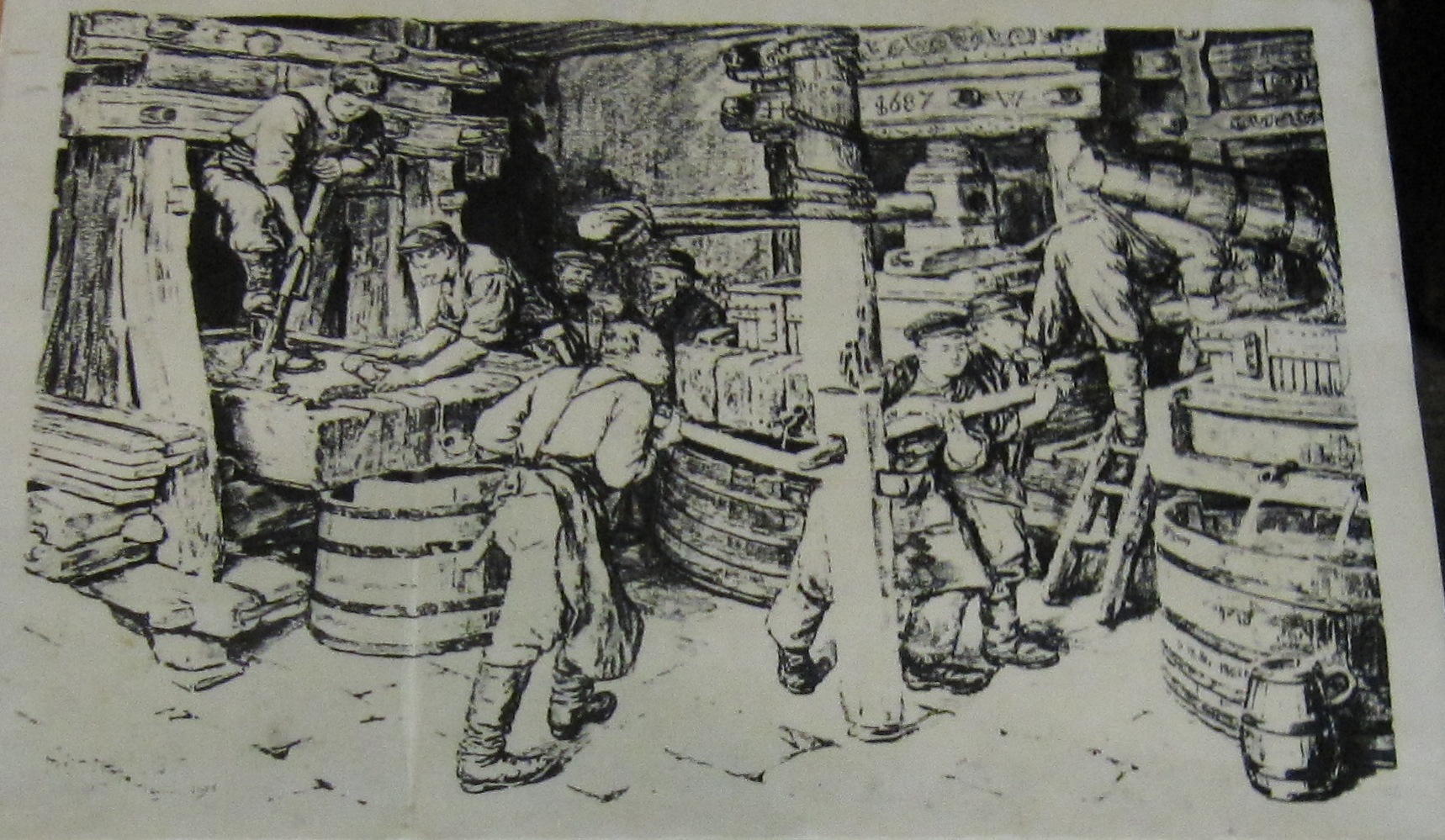

On our way to Matthias’ house that evening, Luzi and her Grandmother stop in the cellar for potato sacks. Why? To trap the elwedritsches, of course.