Reading David Yost’s “The Carousel Thief” in The Cincinnati Review‘s Summer 2012 issue (*great* story), I came across the word “calliope” again, triggering a vague memory from my research about life in Ohio in the 19th century. The reference occurs in Yost’s story thus:

She glanced around the carousel house with distaste, and for a moment I saw what she probably saw: her friends pacing the orange polyester carpet, staring out at the maples and sweetgums of Washington Park as the calliope played and they snacked on caviar and quail brains or whatever rich people serve to other rich people to impress them.

In context, you get the idea of what “calliope” signifies — not the Greek muse of epic poetry, but that flutey, jangling music that accompanies rides on historic carousels. In the 21st century, to our refined ears that sound is enough to make one cringe, but in the mid-19th century, the music of the calliope was a brand new wonder, a triumphal herald of the modern steam age.

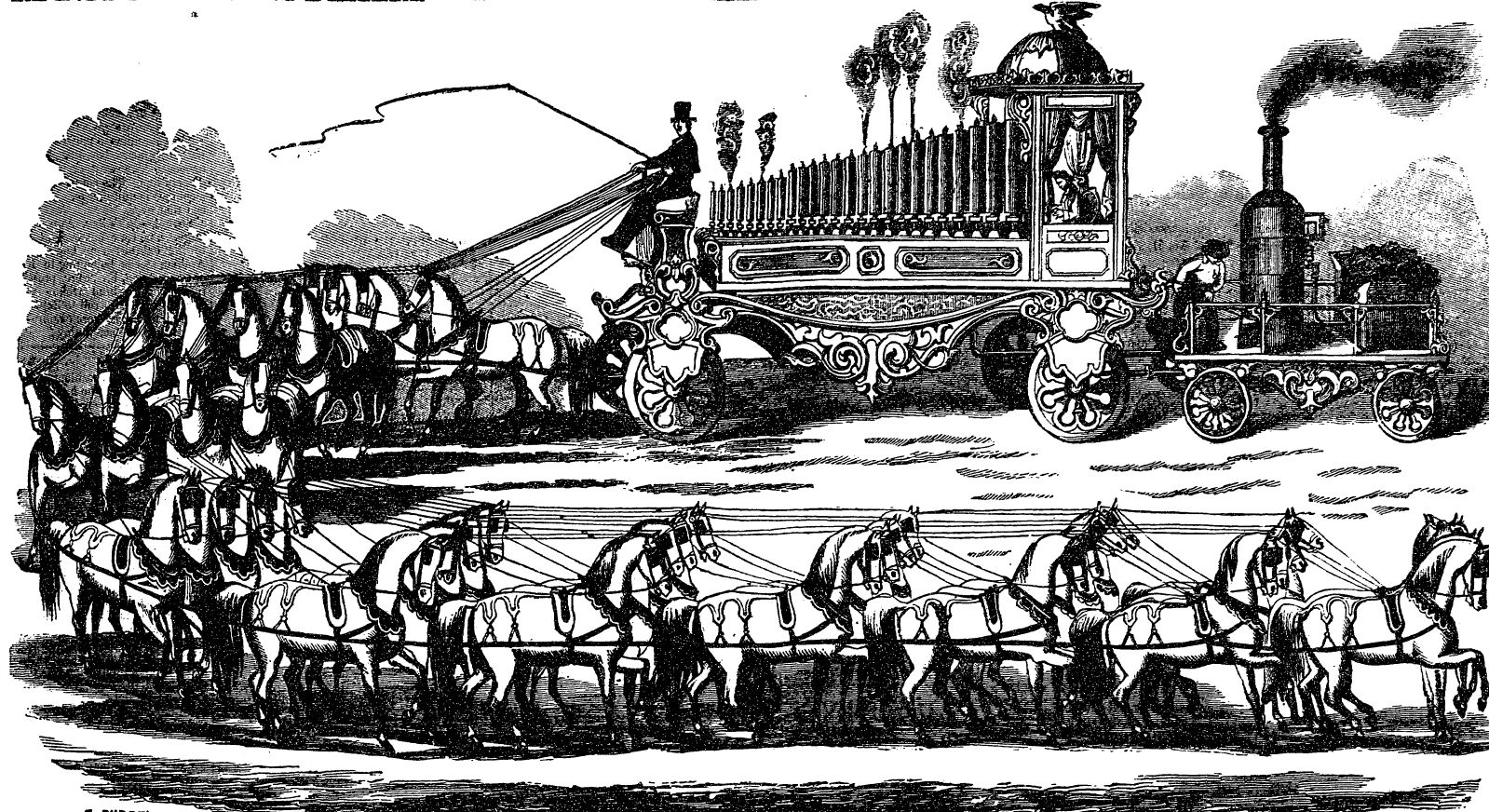

Circa 1858, this 44-pipe Calliope announced the arrival of the Nixon & Kemp Circus in town. The instrument could be heard for ten to twelve miles, was drawn by a team of 40 horses, and cost a fortune ($18,000) to build. It also cost a fortune in upkeep (all those horses to stable and feed, for one thing) so the Calliope was not practical in the long run. But while it lasted, making its circuit through Ohio and other of the U.S.’s 31 states, it created quite a sensation.