On any visit to Freinsheim, Germany, one of the first stops on the “wall walk,” a tour of the narrow corridor that rings the old inner wall, is always at the former home of Hermann Sinsheimer. I snapped this photo of the house (if you look closely, you’ll see the resident cat in the window) and the accompanying stone-etched plaque that adorns the facade on my first day in Freinsheim in September, 2010. Roughly translated, the plaque reads:

On any visit to Freinsheim, Germany, one of the first stops on the “wall walk,” a tour of the narrow corridor that rings the old inner wall, is always at the former home of Hermann Sinsheimer. I snapped this photo of the house (if you look closely, you’ll see the resident cat in the window) and the accompanying stone-etched plaque that adorns the facade on my first day in Freinsheim in September, 2010. Roughly translated, the plaque reads:

The lawyer, writer, and journalist Hermann Sinsheimer was born in this house on the 6th of March 1883. His passion for theater and literature before 1933 drove him to write what he observed of German cultural life. Also, what he wrote in exile was influenced by his happy childhood in Freinsheim. He died far from home, in London, in 1950.

A more complete write-up of the life of Hermann Sinsheimer can be found here, at the AJR (Association of Jewish Refugees) Journal.

While Herman Sinsheimer has languished in obscurity for decades, of late, several books have been published of his work. One is the letters of Hermann Sinsheimer, written while he was in England back to his friend Frida Schaffner in Freinsheim. Dr. Hans-Helmut Görtz edited these letters with Erik and Gabriele Giersberg. They’ve been published in a comprehensive book Briefe aus England in die Pfalz. The book (768 p., hardcover, many photographs) is edited by the Stiftung zur Förderung der Pfälzischen Geschichtsforschung in Neustadt an der Weinstraße. It costs 49 Euros. Whoever is interested in buying a copy should send Dr. Görtz an email at hhgoertz@t-online.de.

Another book, just released and available on Amazon-UK, is an uncensored release of Sinsheimer’s 1953 autobiography Gelebt Im Paradies, published in 2013 by Deborah Vietor-Engländer. This book includes Sinsheimer’s childhood reminiscences, his reflections on anti-Semitism, on accounts of his days in Munich and Berlin, and of living in exile with fellow German Jewish refugees in England during and after the war. The book is available here: Amazon.co.UK.

The book jacket reads (translated from the German):

Hermann Sinsheimer (1883-1950), theater director, theater critic, editor of Simplicissimus and editor of the Berliner Tageblatt, wrote his autobiography “Gelebt im Paradies” in the Palatinate, in Munich and later in Berlin, completing it during his exile in England starting in 1938. In the book, he provides portraits of his contemporaries, from Erich Mühsam to Joachim Ringelnatz, from Alfred Kerr to Frank Wedekind.

Was Germany once a paradise? In Sinsheimer’s youth in the Palatinate, certainly, but in retrospect in exile Sinsheimer also reveals the fullness of the paradise lost he suffered during his years in Munich and Berlin, the destruction he witnessed, and his insights and memories of historical events.

Lived in Paradise is a first release, because here the text kept out of the 1953 imprint has been returned in its original, uncensored form, to properly stock the shelves of German literature. Sinsheimer’s autobiographical essay Deutschland, not included previously, is a document free of hate, a reflection of the exile as he considers German thinking of tomorrow. This text is published here for the first time in German. The political writer reflects on what happened, why the Germans could have done what they did, driving the Jews, including large parts of the scientific and artistic intelligentsia, out of the country. In 1942, Sinsheimer asks: What should be done after the war with Germany is lost?

Yes, the book is in German, but if you dare, I highly recommend delving into the observations and insights of this thoughtful, courageous man.

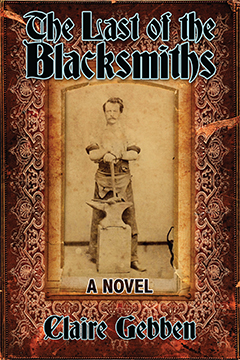

My book is out in stores and online. Reviews are starting to come in on GoodReads, at Morganti Writes and on Amazon.

My book is out in stores and online. Reviews are starting to come in on GoodReads, at Morganti Writes and on Amazon.