I am descended of “keepers,” people who held on to belongings long beyond their usefulness. Or so I used to think.

I am descended of “keepers,” people who held on to belongings long beyond their usefulness. Or so I used to think.

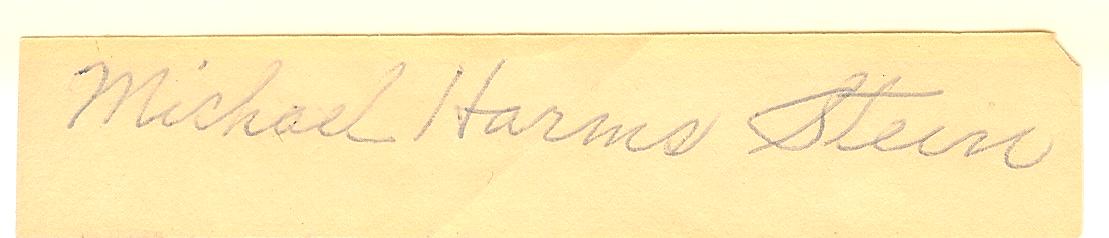

As I’ve spent the last couple of years researching my great-great grandfather, I’ve made discoveries of some of his belongings. In fact, these days I possess a small “Michael Harm museum”: mid-nineteenth letters and photographs, a gold heart necklace he purchased for my grandmother, and this beer stein, which I recently picked up from my brother’s house. (Thanks, Craig.) How do I know the latter once belonged to Michael Harm? Because of this bit of paper tucked inside.

For my German side of the family, Michael Harm was our “point of entry” to America. Perhaps this is why there appears to have been a cult of reverence around the man. When I was child, my grandmother and my father were still telling stories about Michael Harm’s Atlantic voyage and Cleveland carriageworks, more than one hundred years after he made the journey, and sixty years after the Harm & Schuster Wagons and Carriages had closed its doors for good.

His daughter Lucy drew this painstakingly detailed portrait of him (left), poster-sized and framed, based on this photograph, an honor not bestowed on any other member of the family.

His daughter Lucy drew this painstakingly detailed portrait of him (left), poster-sized and framed, based on this photograph, an honor not bestowed on any other member of the family.

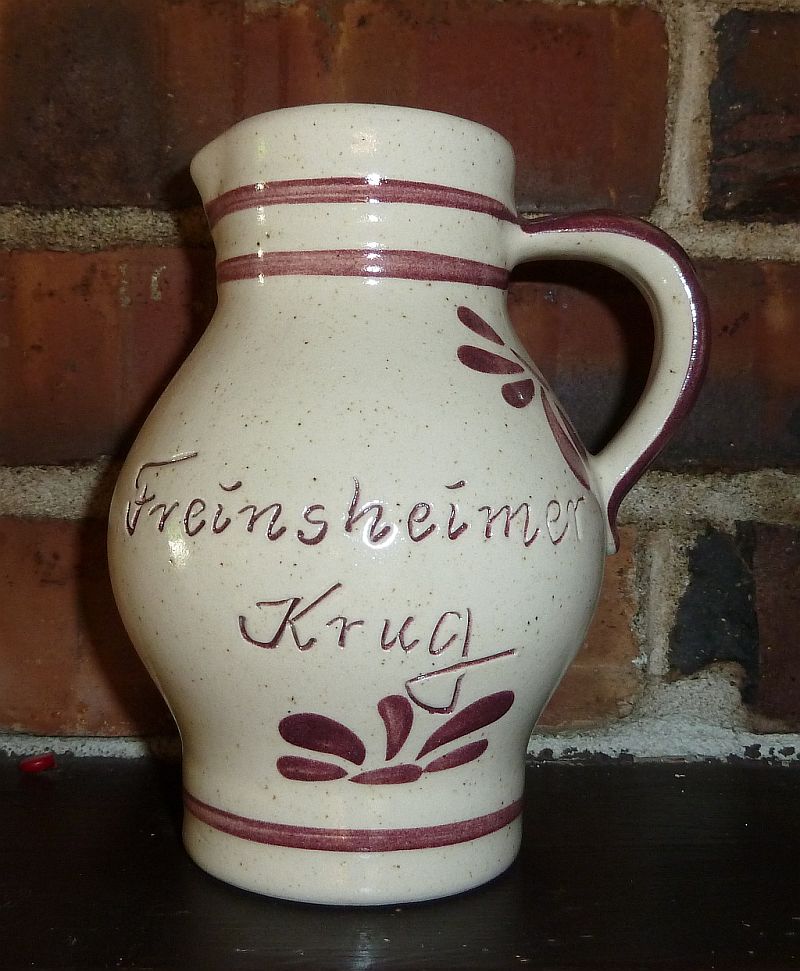

Michael Harm may have been attached to his beer stein, but he hailed from the Palatinate, the southern Rhineland region. Wine country, that is. When my relatives visited from that region of Germany last spring, they brought me this gift, a replica of an old “Freinsheimer Krug,” or wine-drinking jug.

Michael Harm may have been attached to his beer stein, but he hailed from the Palatinate, the southern Rhineland region. Wine country, that is. When my relatives visited from that region of Germany last spring, they brought me this gift, a replica of an old “Freinsheimer Krug,” or wine-drinking jug.

An old object for the shelf, no longer of use? Think again. Before disposable plates and cups, how did we manage? Apparently, people used to carry around their own crockery. Some cultures still do this today. In the 1990s, I had the privilege of being a guest at a Makah Native American Potlatch at Neah Bay. In addition to the generous custom of gift-giving, the respect for tribal elders, and the moving dances and songs, what struck me about the gathering was how all the Makah families brought baskets containing their own tableware–plates, cups, silverware. When the potlatch was over, they packed up their dishes to bring home and wash. It seemed a laudable, sustainable way of living, a way to keep trashbarrels (and landfills) from brimming over with paper plates and cups and plastic eating utensils.

At the time, I wondered why my own culture did not do this. Now I realize, in the not-so-distant past, it was how things were done. It may be an old-time way of thinking but it’s good enough for me.