Here’s a picture of Cleveland in 1858, the meandering Cuyahoga River, the pastures and small city ambiance, the long Lake Erie shoreline to the north. Just to the right of this scene, a ravine ambles off the Cuyahoga to the south and east, named after one of Cleveland’s earliest European inhabitants, Judge Kingsbury, a gully that used to demarcate the southern border of the town.

Here’s a picture of Cleveland in 1858, the meandering Cuyahoga River, the pastures and small city ambiance, the long Lake Erie shoreline to the north. Just to the right of this scene, a ravine ambles off the Cuyahoga to the south and east, named after one of Cleveland’s earliest European inhabitants, Judge Kingsbury, a gully that used to demarcate the southern border of the town.

Kingsbury Run is probably best known these days for the Kingsbury Run “torso murders” of the 1930s. I found this description of it on the trutv web site.

Kingsbury Run cuts across the east side of Cleveland like a jagged wound, ripped into the rugged terrain as if God himself had tried to disembowel the city. At some points it is nearly sixty feet deep, a barren wasteland covered with patches of wild grass, yellowed newspapers, weeds, empty tin cans and the occasional battered hull of an old car left to rust beneath the sun. Perched upon the brink of the ravine, narrow frame houses huddle close together and keep a silent watch on the area. Angling toward downtown, the Run empties out into the cold, oily waters of the Cuyahoga River.

—Crime Library, “The Kingsbury Run Murders or Cleveland Torso Murders“

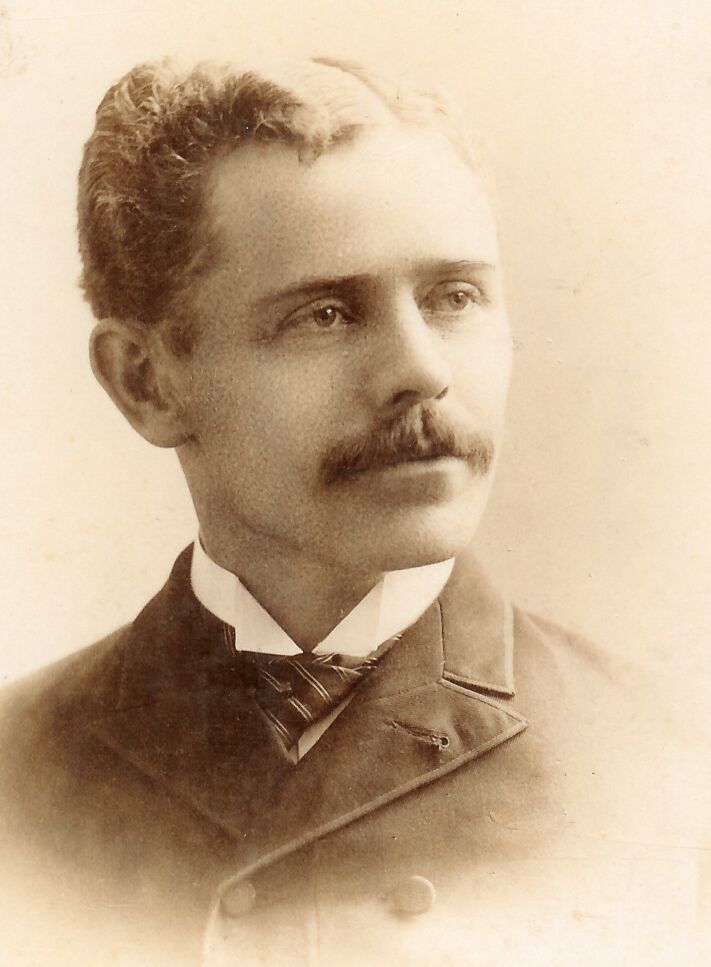

Somehow, growing up, I missed the story about the Kingsbury Run Murders, but I did hear of the historic danger of Kingsbury Run dating back into the 19th century. My father used to tell this story. “Before they built the E. 55th St. bridge [completed for the first time in 1898], your great-grandfather Hoppensack had to walk through Kingsbury Run each day on his way to and from the bank, so he always carried a gun. It was a jungle down there, overgrown and full of vagrants.”

Somehow, growing up, I missed the story about the Kingsbury Run Murders, but I did hear of the historic danger of Kingsbury Run dating back into the 19th century. My father used to tell this story. “Before they built the E. 55th St. bridge [completed for the first time in 1898], your great-grandfather Hoppensack had to walk through Kingsbury Run each day on his way to and from the bank, so he always carried a gun. It was a jungle down there, overgrown and full of vagrants.”

But it was not always so. Here’s a story found in the book “The genealogy of the descendants of Henry Kingsbury.”

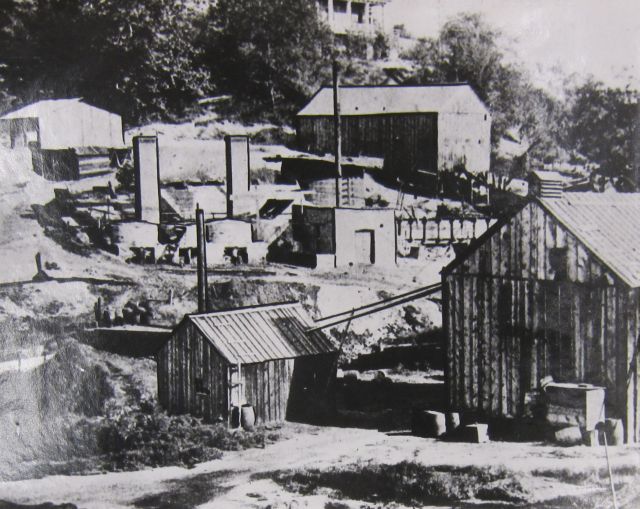

In 1800, Governor St. Clair appointed Mr. Kingsbury Judge of the Court of Common Pleas and Quarter Session of the County. The first session is said to have been held in the open air, between two corn-cribs, Judge Kingsbury occupying a rude bench beneath a tree, the jurors sitting about on the grass, and the prisoners looking on from between the slats of the corn-cribs. A brook running into the Cuyahoga is called Kingsbury Run, and is the only memorial which has been dedicated to the first settler. At the mouth of Kingsbury run are the works of the Standard Oil Company.

Can I visit Kingsbury Run today, you might ask? Not exactly. The Van Sweringens bought up Kingsbury Run property in the early 20th century, and installed a four-track railroad line through it. Gone (underground?) is the brook: today, Kingsbury Run is the corridor of the Rapid Transit Line between E. 30th and Shaker Blvd.