In this morning’s paper, I sat down to an article in the Seattle Times that began “Few have heard of the SS Central America. But it has a place in history because of what happened over three days, beginning on Sept. 9, 1857.”

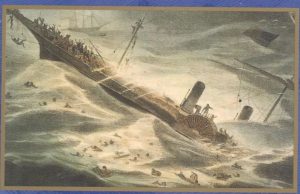

I’m one of the few. I first heard of the SS Central America, the “Ship of Gold” when researching the life trajectory of my German immigrant ancestor, Michael Harm for my historical novel The Last of the Blacksmiths. Michael Harm arrived in Cleveland, Ohio in July of 1857 to begin a blacksmith apprenticeship with his uncle, and two months later, due to the sinking of the SS Central America, which contained gold intended to back federal paper money, the economy went belly-up. The Panic of 1857 initiated a slump in the U.S. economy that lasted several years.

I’m one of the few. I first heard of the SS Central America, the “Ship of Gold” when researching the life trajectory of my German immigrant ancestor, Michael Harm for my historical novel The Last of the Blacksmiths. Michael Harm arrived in Cleveland, Ohio in July of 1857 to begin a blacksmith apprenticeship with his uncle, and two months later, due to the sinking of the SS Central America, which contained gold intended to back federal paper money, the economy went belly-up. The Panic of 1857 initiated a slump in the U.S. economy that lasted several years.

The sinking of the SS Central America, it turns out, ruined more lives than the 425 people who drowned, the failed businesses, etc. Today’s article is the story of how lives are still being ruined, even in 2019. The book Ship of Gold In the Deep Blue Sea (1998), by Gary Kinder, recounts the original sinking of the SS Central America in 1857 and its consequences, and also treasure-hunting efforts in the Atlantic that occurred from 1986-1988. But it’s not until this year, 2019, that those 13 treasure hunters, “most from the Seattle area,” have finally concluded lengthy court battles and earned a fraction of their find.

They were the engineers, technicians and owners of high-end sonar equipment who were promised a small share of the wreck’s bounty in return for their work, which found the Central America in 1988, some 160 miles off the South Carolina coast, 7,200 feet down on the ocean floor.

It took nearly 30 years of litigation and reams of legal documents before a court settlement got them at least a portion of what they were owed. The last of two payments arrived in February.

Full article in The Seattle Times.

The leader of the expedition apparently absconded with $50 million, suffered a failed marriage, and is now in federal prison.

Trouble in this tale includes the main visionary in the treasure hunt – a man named Tommy Thompson, now 66. He sits in an Ohio federal minimum security prison because he won’t divulge where 500 new gold coins struck from the Central America’s bounty have been hidden.

There’s a life lesson here. We seem bound to allow material things to wreck us. Even Ship of Gold author Gary Kinder, who took ten years to write his book, lost his father and his brother to death during those years, and his mother suffered a series of strokes and had to enter a nursing home. Kinder also mentions in his Acknowledgements that his “daughters have hardly known [him] when he was not working on ‘the book’.” Kinder sums up that these things were “all teachings of the bitter lesson that while we are tending relentlessly to one part of our lives, the other parts do not stand still.”

It strikes me as a reflection of how we survive here, a reminder to appreciate what we have, and just maybe, to focus less on material gain and more on quality time with loved ones.