In my novel research about Highland Scots, a librarian clued me in early on to the existence of the luchd siubhail — the traveling people.

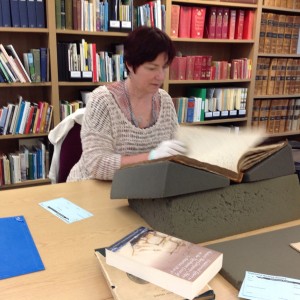

I’d stopped in to inquire about books related to 18th-century Scottish history. The librarian pointed me to the shelf area, then added she was a native of Scotland.

“Really? I’m hoping to write a novel based on the true story of Highlanders who migrated to Ohio around 1800, but resources are hard to find.”

“Oh, right!” she commiserated. “Very little has survived, since they spoke Gaelic, and their histories were shared by oral tradition, not written down. It’s even worse to turn up anything on the traveling people.”

“Traveling people?”

“Yes, a Highlands version of gypsies. They’re rarely mentioned in histories of Scotland. The traveling people are still around today, though their numbers have shrunk.”

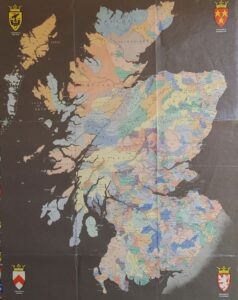

Years passed, and she was right, I didn’t come across mention of the luchd siubhail. Until just the other day, that is, when looking into whisky smuggling. I’d come across a reference to the significant role Highland women played in whisky smuggling, often using specially crafted tins that fit under their skirts. They could smuggle as much as six gallons of whisky at a time that way. But who made the tins? An internet search for “Highland tinsmiths” led me to this Preindustrial Craftmanship website.

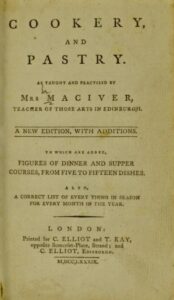

Tinsmiths of the day were also known as tinkers, handy at most repairs. Upon further research, I turned up this book: Last of the Tinsmiths: The Life of Willie MacPhee by Sheila Douglas. In a nutshell:

Tinsmiths of the day were also known as tinkers, handy at most repairs. Upon further research, I turned up this book: Last of the Tinsmiths: The Life of Willie MacPhee by Sheila Douglas. In a nutshell:

Originally [the luchd siubhail] were metalworkers to the ancient clans, forced by the topography of the landscape to travel round the various glens to do their work. They made weapons and ornaments needed by the clansmen. They were also the newsbringers and the entertainers.

Tin lanterns like the one pictured here were a common item crafted by Highland tinsmiths. I took this photo in the tinsmith shop at Colonial Williamsburg.