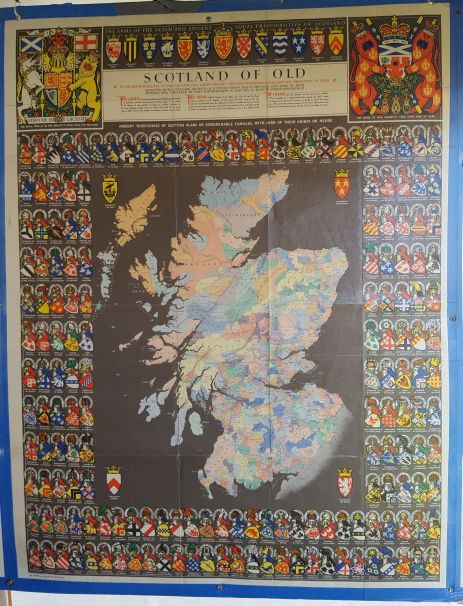

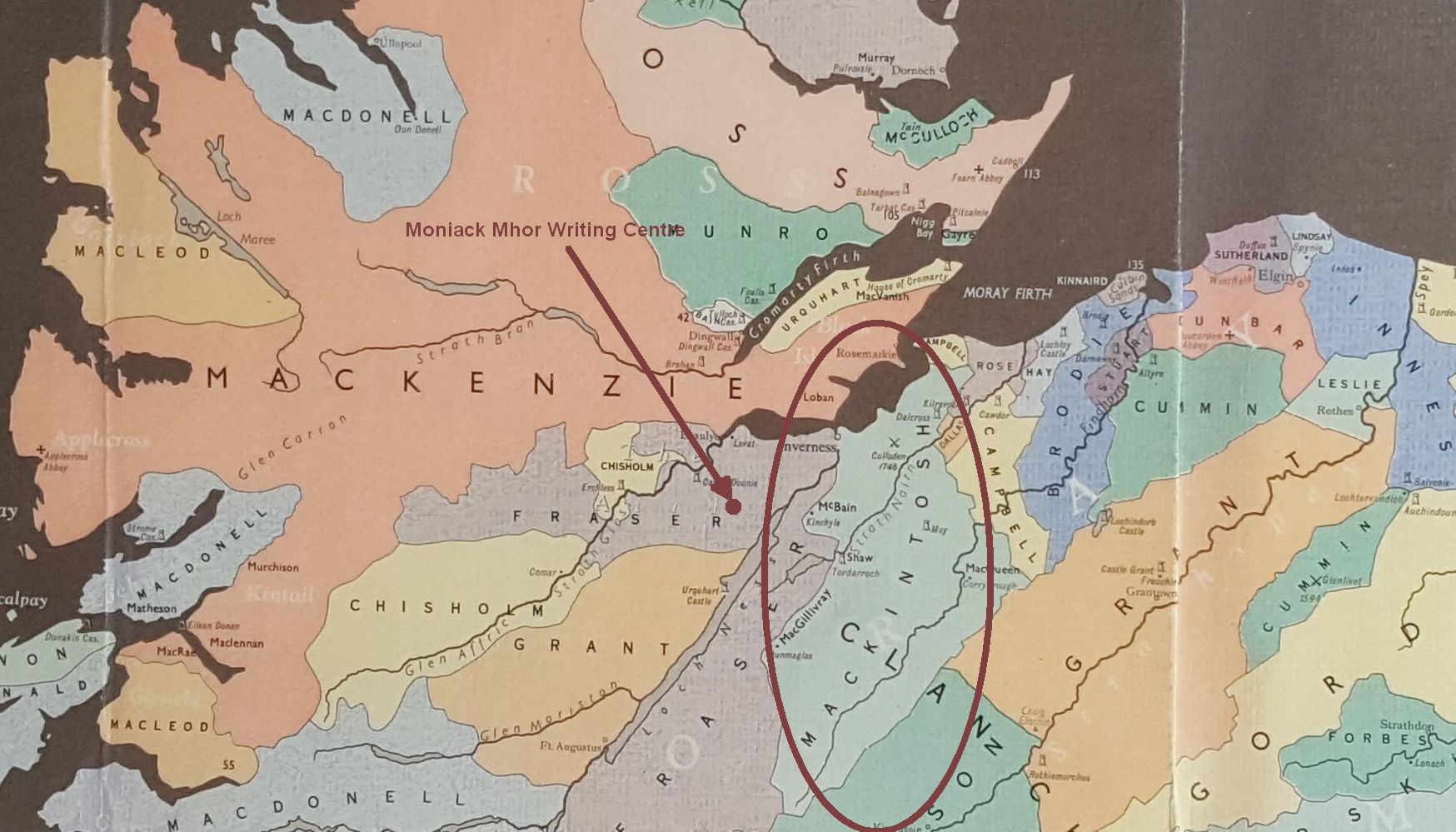

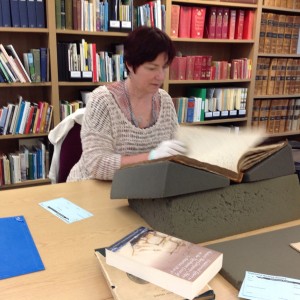

I’m continually impressed by the diversity of characters living in the Highlands of Scotland in the 18th century. Yesterday, I came across a resource at the Inverness Library, a terrific summary of The Old Statistical Accounts. These accounts were sent to Sir John Sinclair in response to a lengthy questionnaire sent out to parish ministers. They often returned them with quite lengthy, colorful descriptions of their parishioners.

Here’s an example, a write-up about “fisherwives.”

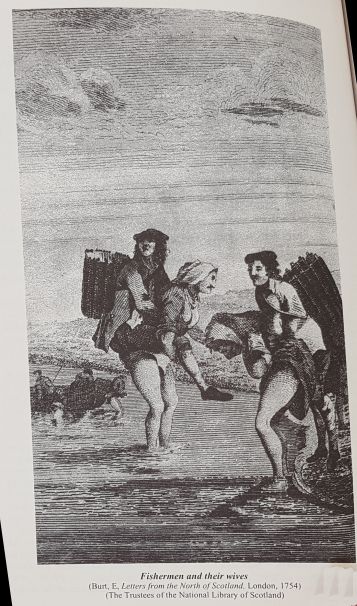

The distinctiveness of the fisherfolk in the numerous fishing villages [of Scotland], especially those of the east coast, is [often] highlighted. … it is of the women that most of the ministers write. The account from Rathven, for example (taking in four fishing towns — Buckie, Port-easy, Findochtie, Port-nockie), states: ‘The fisher-wives lead a most laborious life. They assist in dragging the boats on to the beach, and in launching them. They sometimes, in frosty weather, and at unseasonable hours, carry their husbands on board, and ashore again, to keep them dry. They receive the fish from the boats, carry them fresh, or after salting, to their customers, and to market, at the distance, sometimes, of many miles, through bad roads, and in a stormy season. … many [women] are pretty, and dress to advantage on holidays.’

From “Parish Life in Eighteenth-Century Scotland: A Review of the Old Statistical Account.” Maisie Stevens, Scottish Cultural Press, 1995

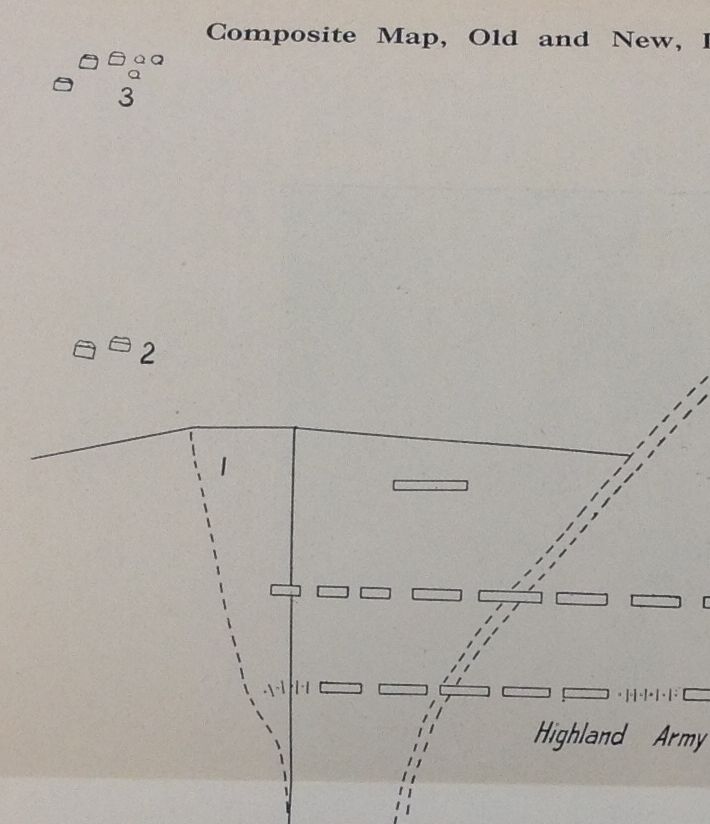

What’s more, this drawing is supplied — a picture of the women carrying their fishermen:

Should you be studying your Highlander genealogy and what your ancestors may have experienced in the late 1700s, I highly recommend this book.