When friends and I get to talking about history, we’ve been known to land on how much things have changed.

“Isn’t it amazing,” one of us will reflect, “how far we’ve come?”

The other will proceed to recount his or her latest realization — how we once called native peoples “savages,” or how slavery was an acceptable practice for way too long.

More than once, I’ve been known to add: “No doubt one day we’ll look back on something we’re doing today and think — Oh my God! How could we not have seen how wrong that was?”

I had an oh-my-God moment the other day when I picked up the August 2013 issue of The Sun magazine and started reading the feature interview: “Keep Off The Grasslands: Mark Dowie On Conservation Refugees.” Dowie’s comments smacked me in the forehead with how regressive my “Left-thinking” has been on the issue of the wilderness. I’ve been a huge fan of national parks and protected wilderness, a backpacker who is strict about the principles of “leave no trace.” I’ve never questioned the notion that wilderness must be defined as a place without people. In the article, interviewer Joel Whitney asks Dowie where that notion came from.

I had an oh-my-God moment the other day when I picked up the August 2013 issue of The Sun magazine and started reading the feature interview: “Keep Off The Grasslands: Mark Dowie On Conservation Refugees.” Dowie’s comments smacked me in the forehead with how regressive my “Left-thinking” has been on the issue of the wilderness. I’ve been a huge fan of national parks and protected wilderness, a backpacker who is strict about the principles of “leave no trace.” I’ve never questioned the notion that wilderness must be defined as a place without people. In the article, interviewer Joel Whitney asks Dowie where that notion came from.

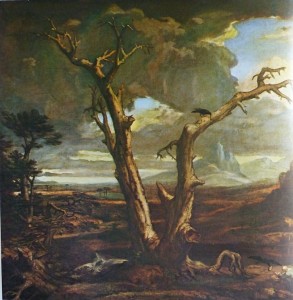

Dowie replies: “It was brought here from Europe by people like [John] Muir, who romanticized wilderness even where it didn’t exist. It was reinforced by artists: painters like Albert Bierstadt and photographers like Ansel Adams. Adams would spend hours with a camera trained on a particular scene that he wanted to shoot, waiting for it to be clear of native people before he clicked the shutter.”

Once the first National Park was established (Yellowstone in 1872), 108,000 parks and protected wilderness areas have been created worldwide, “covering an area equal to the total landmass of Africa.” This is a good thing, right? It would be, if it didn’t mean 20 million indigenous people have lost their lands and livelihoods as a result of protecting this wilderness. The stewards of these lands have been literally kicked off. Worse, conservation groups and big corporations are now colluding in deals that allow natural resources to be extracted from these areas. Oh my God.

That the wilderness and human civilization are separate, I realize now, is a crazy way of thinking. It leads us to behave as if we have nothing to “protect” in our civilized yards, only something to protect afar. It leads us to imagine that the wilderness takes care of itself, when in fact, places like pristine Yosemite were ecologically managed by the Ahwahnechee people, the Serengeti by the Maasai. There’s an incredible essay about this romantic definition — that wilderness happens to be a place where people are not — written by William Cronon: “The Trouble With Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” I highly recommend it.

One response to “Progress”