I’ll admit when I began looking into the 19th century, I had preconceived stereotypes–high-collared, long-sleeved, Victorian era prudes, bombastic orators, a stalwart naïveté about religion, medicine, America, etc., and in general, a less frenetic pace of life. Frequently, however, my 21st century superiority has been caught up short. When the Englishwoman Isabella Bird visited Canada and the States in 1854, she made the following observations, which strike me as  eerily insightful about us today:

eerily insightful about us today:

“While we admire and wonder at the vast material progress of Western Canada and the North-western States of the Union [Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky], considerations fraught with alarm will force themselves upon us. We think that great progress is being made in England, but, without having travelled in America, it is scarcely possible to believe what the Anglo-Saxon race is performing upon a new soil. In America we do not meet with factory operatives, seamstresses, or clerks overworked and underpaid, toiling their lives away in order to keep body and soul together, but we have people of all classes who could obtain competence and often affluence by moderate exertions, working harder than slaves–sacrificing home enjoyments, pleasure, and health itself to the one desire of the acquisition of wealth. Daring speculations fail; the struggle in unnatural competition with men of large capital, or dishonourable dealings, wears out at last the overtasked frame–life is spent in a whirl–death summons them, and finds them unprepared. Everybody who has any settled business is overworked. Voices of men crying for relaxation are heard from every quarter, yet none dare to pause in this race which they so madly run, in which happiness and mental and bodily health are among the least of their considerations. All are spurred on by the real or imaginary necessities of their position, driven along their headlong course by avarice, ambition, or eager competition.” (p.222, My First Travels in North America)

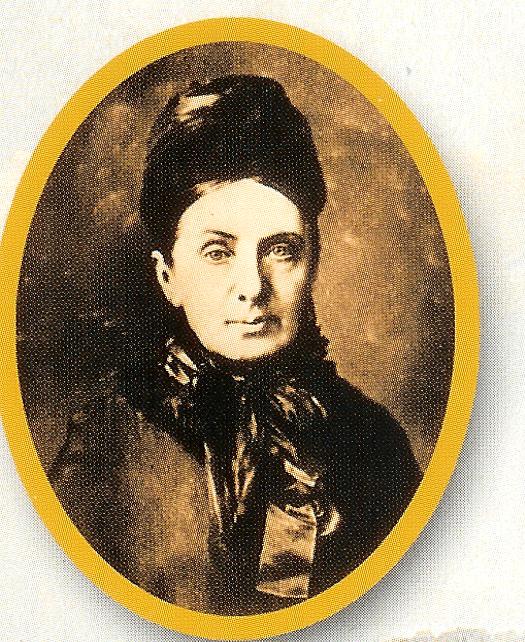

I envy Bird her rigorous meanderings, which included a visit to Niagara Falls, an experience she describes in great, harrowing detail. At age eighteen, according to the Introduction ot First Travels, she had a spinal tumor surgically removed, an operation that was only partly successful, “so her young adulthood was punctuated by long periods in which she would have to spend entire mornings in a semi-recumbent position. Perhaps her doctor realized that many of her physical and emotional problems stemmed from an extraordinary intelligence and a strong personality at odds with a stultifying social enviornment; in any event, he prescribed an extended ocean voyage. In 1854 Isabella’s father gave her £100 and permission to travel as long as the money lasted. She chose to travel to North America and made it last for almost six months.”

The book jacket claims she was “a woman ahead of her time.” Perhaps. Or is this another stereotype to be rethought? To my mind, the countless thousands–many of them women–who emigrated from Europe, leaving hearth and home for places and lives unknown, speak otherwise.

Pingback: Personal travel accounts by 19th century women | Claire Gebben