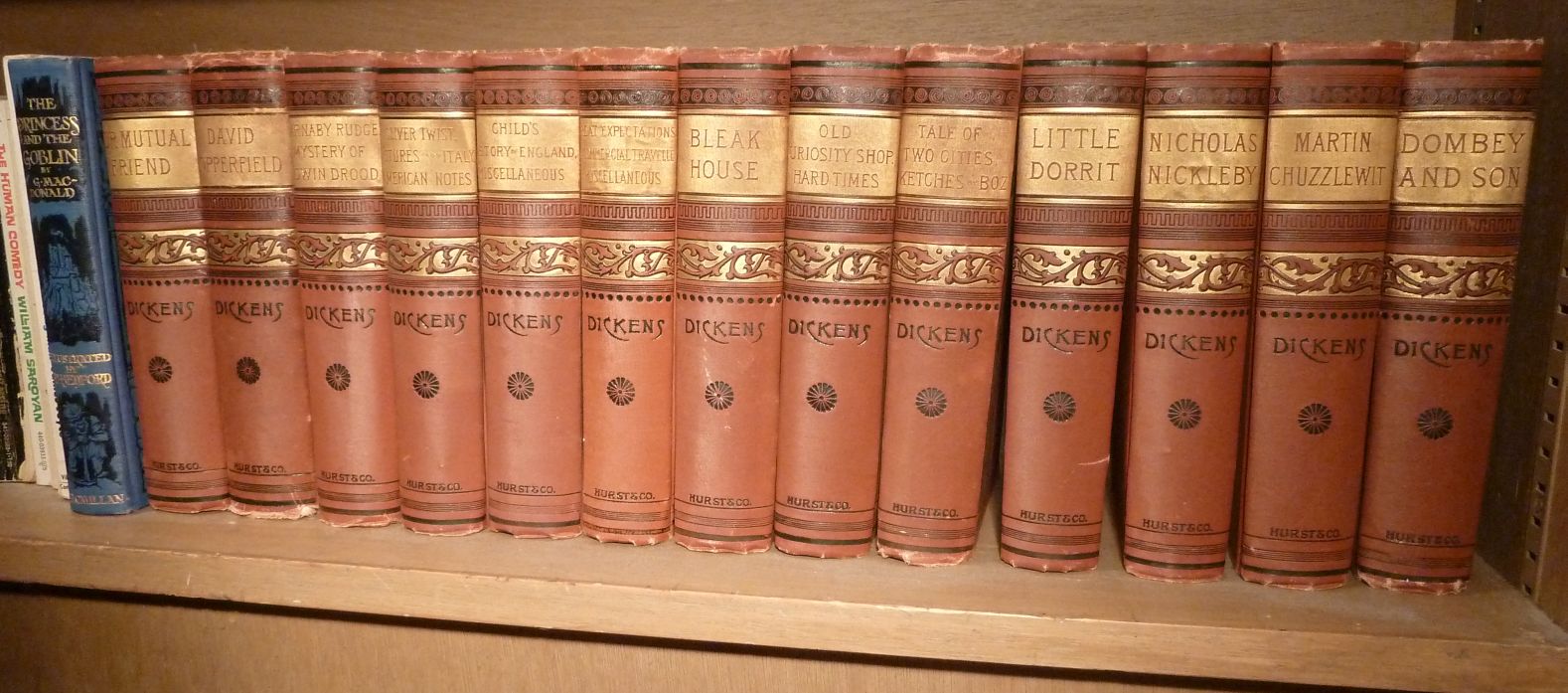

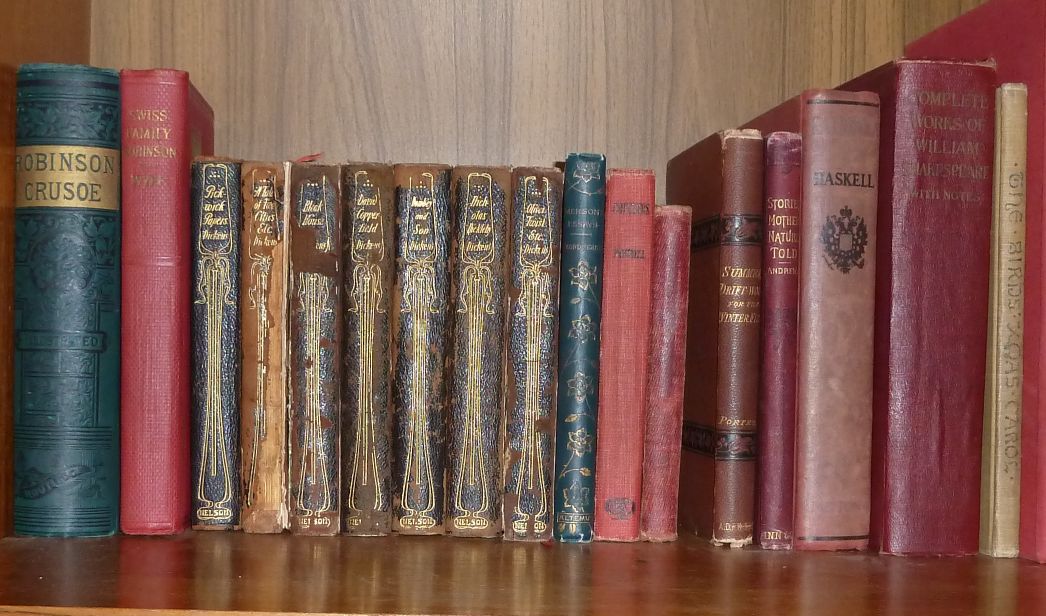

I come from a family of readers. Over the years, as the old people have passed away, their books have sifted down to me. Anthony Trollope, George Eliot, Darwin, Browning, Milton, Moore. Two sets of the complete works of Charles Dickens. This February, in honor of the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Dickens, I wish to champion not only his writing, but how much he wrote. “He was the Spielberg of his day,” my friend Michele said recently. Here’s one example, from an article in the most recent Smithsonian.

I come from a family of readers. Over the years, as the old people have passed away, their books have sifted down to me. Anthony Trollope, George Eliot, Darwin, Browning, Milton, Moore. Two sets of the complete works of Charles Dickens. This February, in honor of the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Dickens, I wish to champion not only his writing, but how much he wrote. “He was the Spielberg of his day,” my friend Michele said recently. Here’s one example, from an article in the most recent Smithsonian.

The two and a half years that the Dickenses spent on Doughty Street [London, 1837-1840] were a period of dazzling productivity … Dickens wrote an opera libretto, the final chapters of The Pickwick Papers, short stories, magazine articles, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickelby, and the beginning of Barnaby Rudge.

(Smithsonian, February 2012, Joshua Hammer)

To his credit, the writing stands the test of time, for the patient reader anyhow. A new film version (the 12th?) of Great Expectations, this one directed by Mike Newell and starring Ralph Fiennes and Helena Bonham Carter, is currently in the works. And did you know? There’s a Dickens World Theme Park. (Where have I been?) Next Dickens read on my list is Martin Chuzzlewit, since I hear it’s based on the author’s 19th century travels in America.

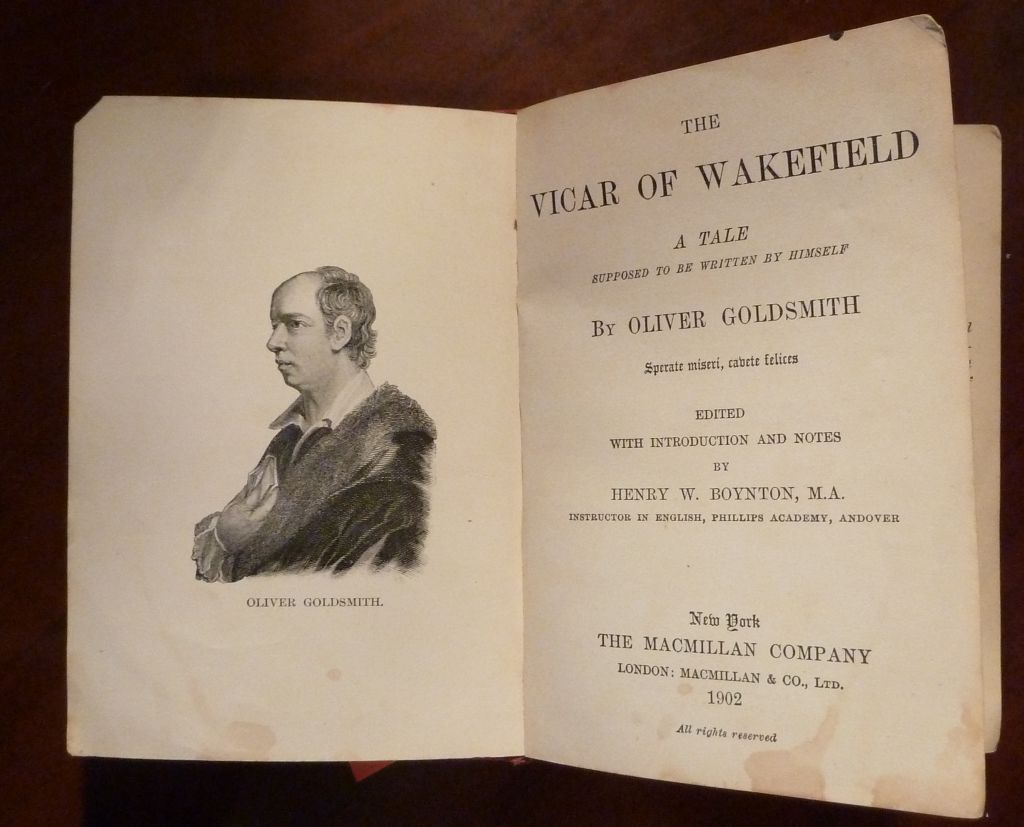

Meanwhile, a popular author of the mid 18th-century languishes in relative obscurity: Oliver Goldsmith. Who? The author of The Vicar of Wakefield and the play She Stoops To Conquer. Duh. There’s a terrific write-up of this Irish author at Editor Eric. In Editor Eric’s opinion, the writing in The Vicar is less than stellar. Still, as described by Oscar Ameringer, 19th century German immigrant to Cincinnati, Goldsmith’s book had redeeming value as a teaching tool:

What a marvelous teacher that spinster lady [Cincinnati librarian] was! “You are young enough to learn to read English,” she told me one day. “Unfortunately, there are no schools for your kind and you haven’t got the money for private lessons, but if I give you an English book I think you can almost read, will you try?”

I would. The book was The Vicar of Wakefield, by Goldsmith. There were many words in it I could not make out; sometimes whole sentences and paragraphs were too obscure for me. But when I got to the end I knew fairly well what the story was about. I had even—and oh, what joy—caught a fine joke in the book. It was the one when the vicar told how he rid himself of unwelcome friends and relatives by simply lending them a sheep, a little money, or a pair of boots, whereupon they usually remained absent for a long while.

Goldsmith has endured in print for centuries, too, just not as prolifically as some.

Goldsmith has endured in print for centuries, too, just not as prolifically as some.